Brittny Sciarra Murphy and Karese Laguerre write about BROOMS screening in the dental office that can identify oral dysfunction for your patients’ sleep and overall health.

by Brittny Sciarra Murphy, RDH, BS, MAS, COM, QOM, and Karese Laguerre, RDH, MAS

by Brittny Sciarra Murphy, RDH, BS, MAS, COM, QOM, and Karese Laguerre, RDH, MAS

Introduction

Don’t ignore the elephant in the mouth. Well the elephant trunk that’s in the mouth. More commonly known as the tongue, this essential organ aids us in respiration, digestion, speech and swallowing. Yet very few acknowledge the essential influence this muscular hydrostat has on oropharyngeal space during respiration. Each muscle intertwines and relies on each other for alternate movements that enable the tongue to bend, twist, cup, hump, retract, etc.

Any change or dysfunction in these hydraulics encourages compensatory muscle function of the lips, cheeks, soft palate, and/or pharynx. Dental sleep medicine can use these hydraulics to their advantage with the assistance of myofunctional therapy. Imagine taming an elephant trunk with a bit of plastic. Numerous challenges present including but not limited to controlling each muscle, taming an anxious animal, and retention. Not unlike fitting and titrating an oral appliance within a mouth of dysfunction on a skeptical patient with a strong gag reflex.

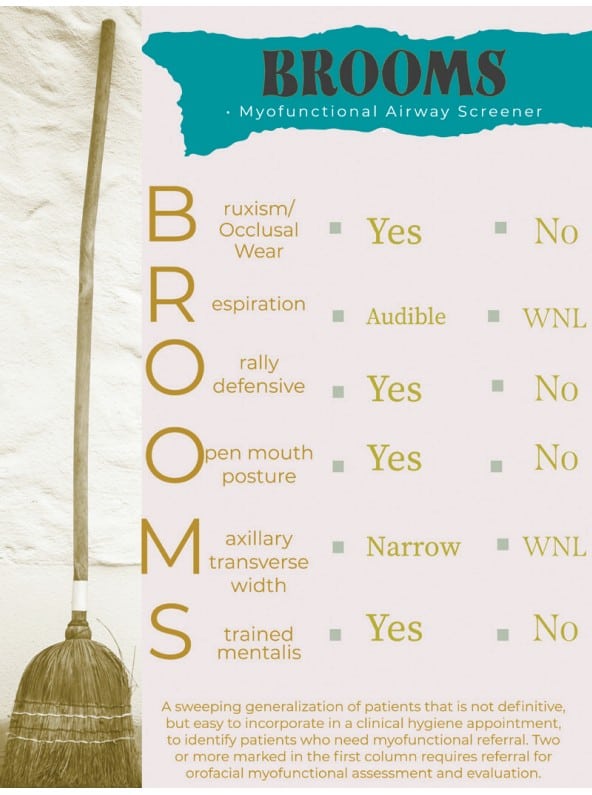

The ability to identify oral dysfunction is vital to case success in a dental sleep practice. Dental schedules often leave little room for new processes. Easy to integrate, the B.R.O.O.M.S. screener is a quick resource for clinical use. Efficiently observe strong indicators during oral cancer screening and extraoral examination. Two or more noted in the first column requires referral for orofacial myofunctional assessment and evaluation.

Screening with BROOMS

Bruxism/Occlusal Wear

How often do patients come in with pain or tenderness in the masticatory muscles? How often do patients complain of tooth pain, but upon oral and radiographic evaluation, there are no significant findings? Have you considered the possibility of it being referred pain due to bruxism? Occlusal wear is a common finding in clinical practice. Our trained response is recommending a traditional night guard. While some of us still make this recommendation, we are here to argue that. We believe in an airway first model. It is critical to rule out airway obstruction or issue before recommending a night guard. Many airway focused dental providers no longer utilize traditional night guards in their armamentarium. According to sleep medicine specialist Jerald Simmons, MD and sleep dental specialist Ronald Prehn, DDS, “when most patients exhibit obstructive respirations during sleep the mandible falls back bringing the back of the tongue with it. This triggers a series of events that in some people results in a reflexive attempt to open up the airway by increasing masseter tone. This brings the mandible forward and in many patients improves respirations. We postulate that nocturnal bruxism is a compensatory mechanism of the upper airway to help overcome upper airway obstruction by activation of the clenching muscles which results in bringing the mandible, and therefore the tongue, forward.”2

Myofunctional therapy can aid in the patency of the upper airway. According to Guimarães et al, 2018 “oropharyngeal exercises significantly reduce OSAS (obstructive sleep apnea syndrome) severity and symptoms and represent a promising treatment for moderate OSAS.”3 A clinical study conducted by Messina et al., 2017 documents the benefits of myofunctional therapy on bruxism. This study showed that myofunctional therapy can be “an effective therapeutic strategy in regard to the treatment of muscle facial pain and hypertonia of the chewing and swallowing muscles. All treated patients had a reduction of facial pain and reduced the number of bruxism episodes per hour, and in many cases such episode disappeared.”4 Another indication to look for intra-orally is the presence of maxillary or mandibular tori. According to research, tori are associated with presence of abnormal tooth wear due to the abnormal pressure on the teeth.5

Respiration

Have you ever considered your patient’s mode of breathing and how that can impact their dental health and overall health? This is something that can be easily done through simple observation. We welcome our patients from the waiting room. Prior to calling their name, watch them in their natural state. Are they breathing through their nose or their mouth? You can even take time to observe this while they are sitting in the dental chair. Where is the primary movement of breathing coming from, their chest or their diaphragm? Are they breathing shallow? Is their breathing audible? Mouth breathing can negatively impact the development of the craniofacial respiratory complex, a term coined by Kevin Boyd, DDS. Mouth breathing can also impact the retention of orthodontic treatment. According to Zhao et al., 2021, mouth breathing affected facial skeletal development and malocclusion in children. “The mandible and maxilla rotated backward and downward, and the occlusal plane was steep. In addition, mouth breathing presented a tendency of labial inclination of the upper anterior teeth.”6

In 1907, Dr. Alfred Rogers published Malocclusion of the Teeth, where he recognized the influence of mouth breathing on oral rest posture and successful orthodontic treatment.7 Optimal oral rest posture includes the entire tongue resting in the roof of the mouth, lips closed, and dominant nasal breathing. This posture should be dominantly maintained during the day and night. Optimizing oral rest posture is the ultimate goal of a myofunctional therapy program, and therefore, should always be included in a patient’s treatment whose dominant mode of breathing is orally. As dental clinicians, we are aware of the harmful effects of mouth breathing on the progression of periodontal disease and increased caries risk. We must keep in mind the oral systemic connection, our mouth is the gateway to the rest of our body.

Oral defensiveness is the battle between your hands and their lips…

Orally Defensive

If you have ever reviewed your schedule for the day and begin dreading taking that full mouth series on the patient with a severe gag reflex, you are familiar with oral defensiveness. It is that familiar battle between your hands and their lips when the patient has so much tension in their orofacial muscles that it hinders visualization of their teeth as you fight to retract. What about the patient whose tongue is everywhere your instrument goes? I remember when I was practicing clinically, there were some patients I had to stand up for to get enough traction to pull down their lower lip and scale the mandibular anterior dentition. Why are these patients so orally defensive? What if we told you that a gag reflex can be a protective mechanism for one’s airway? Each situation depicted above can suggest symptoms of orofacial dysfunction and signal further investigation with a comprehensive orofacial myofunctional evaluation.

Lingual control and optimal lingual function play a crucial role in optimal craniofacial growth and development, mastication, swallowing, speaking, and keeping the upper airway open during sleep. Myofunctional therapy includes exercises to strengthen the tongue and orofacial muscles. Oropharyngeal exercises effectively modify tongue tone.8

Open Mouth Posture

Also in the waiting room breathing can be observed. Examine whether their mouth posture is open or closed by noting if their lips are together or apart. Continue observing throughout the entire recare appointment. Any time the patient is not actively talking, take silent note of how they are posturing their lips and tongue at rest. Additionally, dried or cracked lips may be observed. This is indicative of open mouth posture or a mouth breathing habit. Some patients may even apply chapstick while they are in your dental chair. Ask them if that’s a pretty common occurrence. Should you notice any asymmetries in their lips, be aware that a flaccid, inverted or rolled out, lower lip can suggest an open mouth posture or mouth breathing habit as well.

What is the root cause of this open mouth posture? We should rule out airway obstruction. A myofunctional evaluation along with a CBCT or referral to an ENT is a good starting point. It is imperative to work collaboratively with an otolaryngologist, or ENT, to evaluate for nasal patency. Airway impatency can be due to allergies, enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids, nasal polyps, enlarged nasal turbinates, deviated septum, or tethered oral tissues. As a result of the open mouth posture, it is not unlikely to find low tongue posture, a reverse or tongue thrust swallowing pattern, and/or malocclusion.

Maxillary Transverse Width

We were created to have a full dentition, thirty-two teeth. This means there should be enough room for all teeth to erupt. How many patients a day do you see with a complete dentition, that is third molars included? More often, we see patients present with some form of dental crowding or malocclusion.

Measuring maxillary transverse width can be done with the simple use of a cotton roll. Dr. James A. McNamara gives us the range of 36 to 39mm indicating a maxillary arch that can accommodate a dentition without crowding or spacing.9 We are measuring from tooth #3 to #14 on the maxillary arch. First, take a cotton roll and measure it with your periodontal probe. Cotton rolls are generally about 36-37mm. Second, hold the cotton roll up between tooth #3 and #14. Is the cotton roll getting squished or is there ample space?

When I explain this to patients, I take out my skull that is color coded and I show them their maxilla. I then ask them what else does this bone make up? Typically, their answer will be the nose. I even ask this question to children. When discussing the importance of nasal breathing and sufficient transverse development, we must remember that the maxilla is the floor of the nose and the lateral walls of the nasal cavity. When the maxilla develops narrow, we typically see insufficient oropharyngeal space. When assessing craniofacial develop, or the lack of, we must not ignore tongue rest posture. Where the tongue rests matters. According to Dr. Ben Miraglia, “the tongue should fit in the roof of your mouth, like your car fits in your garage”. Often times we hear, “my tongue is just too big for my mouth.” There is a book written by Dr. Felix Laio, Six-Foot Tiger, Three-Foot Cage, that presents the mouth as too small for the tongue.

In utero, the tongue begins to shape the structure of our jaws and nasal airway. The tongue aids in the architecture of our jaw by pushing the palate laterally and anteriorly. It is the counterbalancing forces that allow our arches to reach their fullest potential and develop proper bone growth.

Strained Mentalis:

Patients with true lip incompetence will exhibit mentalis strain. Mentalis strain presents as dimpling over the mentalis muscle. An overdeveloped mentalis muscle may be the result of insufficient craniofacial development. You will see overactivation of the mentalis muscle present in patients with increased vertical growth. Those are your patients with gummy smiles. A retrognathic mandible or extreme overjet may also cause the mentalis to be strained due to the compensatory pattern to keep the lips closed.

Conclusion

We strongly encourage you to begin using the ‘BROOMS’ screener in your practice. It would be beneficial to not only your patients overall health and efficacy of their oral appliance therapy, but your practice growth and retention to stop ignoring the elephant in the mouth.

Screening in the dental office takes many forms. Read about “Home Sleep Testing, Telemedicine, and the Impact on Dental Sleep Practices” and subscribers can take the quiz to receive 2 CE credits! https://dentalsleeppractice.com/ce-articles/home-sleep-testing-telemedicine-and-the-impact-on-dental-sleep-practices/

- KIER, WILLIAM M., and KATHLEEN K. SMITH. “Tongues, Tentacles and Trunks: The Biomechanics of Movement in Muscular-Hydrostats.” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 83, no. 4, 1985, pp. 307–324., https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1985.tb01178.x. Accessed 2022.

- Simmons J, Prehn R. Nocturnal Bruxism as a Protective Mechanism against Obstructive Breathing during Sleep. Accessed December 19, 2021. https://csma.clinic/Bruxism_Poster.pdf

- Guimaraes KC, Drager LF, Genta PR, Marcondes BF, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of Oropharyngeal Exercises on Patients with Moderate Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. American Journal of respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.200806-981OC. Published February 19, 2009. Accessed December 19, 2021.

- Messina, G., Martines, F., Thomas, E., Salvago, P., Menchini Fabris, G., Poli, L. and Iovane, A., 2021. Treatment of chronic pain associated with bruxism through Myofunctional therapy. [online] NCBI. Available at: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5656808/> [Accessed 19 December 2021].

- Bertazzo-Silveira, E., Stuginski-Barbosa, J., Luís Porporatti, A. and Dick, B., 2017. Association between signs and symptoms of bruxism and presence of tori: a systematic review. [online] Research Gate. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313834203_Association_between_signs_and_symptoms_of_bruxism_and_presence_of_tori_a_systematic_review> [Accessed 19 December 2021]

- Zhao Z, Zheng L, Huang X, Li C, Liu J, Hu Y. Effects of mouth breathing on facial skeletal development in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis – BMC Oral Health. BioMed Central. https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-021-01458-7. Published March 10, 2021. Accessed December 19, 2021.

- Angle Orthod (1973) Effect of Mouth Breathing on Dental Occlusion 43 (2): 201–206.

- Villa MP;Evangelisti M;Martella S;Barreto M;Del Pozzo M; Can myofunctional therapy increase tongue tone and reduce symptoms in children with sleep-disordered breathing? Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28315149/. Published March 18, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2021.

- McNamara JA. Maxillary transverse deficiency. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2000;117(5):567-570. http://www.dent.umich.edu/sites/default/files/departments/opd/160.pdf.

Brittny Sciarra Murphy, RDH, BS, MAS™, COM®, QOM®, is a registered dental hygienist; myofunctional therapist; Buteyko Breathing educator; author; and key opinion leader in myofunctional therapy, sleep, and functional breathing. Brittny is the founder of CT Orofacial Myology and cofounder of MyoAir, both practices focus on preventing and treating the causes of orofacial myofunctional disorders, getting to the root of the problem instead of merely treating the symptoms. Brittny is an educator for Airway Health Solutions and Dental Sleep Toolbox. She is also the face behind the podcast, “I Spy with My Myo Eye.”

Brittny Sciarra Murphy, RDH, BS, MAS™, COM®, QOM®, is a registered dental hygienist; myofunctional therapist; Buteyko Breathing educator; author; and key opinion leader in myofunctional therapy, sleep, and functional breathing. Brittny is the founder of CT Orofacial Myology and cofounder of MyoAir, both practices focus on preventing and treating the causes of orofacial myofunctional disorders, getting to the root of the problem instead of merely treating the symptoms. Brittny is an educator for Airway Health Solutions and Dental Sleep Toolbox. She is also the face behind the podcast, “I Spy with My Myo Eye.” Karese Laguerre, RDH, MAS™, is a registered dental hygienist and myofunctional therapist. She founded The Myo Spot, a practice aimed at amplifying oral wellness to whole body wellness. Through tele-therapy, she helps clients of all ages overcome tongue ties, TMJ disorders, sleep apnea, grinding, anxiety, and various breathing and orofacial dysfunction. Passionate about education and self-help, she published Accomplished: How to Sleep Better, Eliminate Burnout and Execute Goals. When not working with clients globally, she spends time with her husband and four kids.

Karese Laguerre, RDH, MAS™, is a registered dental hygienist and myofunctional therapist. She founded The Myo Spot, a practice aimed at amplifying oral wellness to whole body wellness. Through tele-therapy, she helps clients of all ages overcome tongue ties, TMJ disorders, sleep apnea, grinding, anxiety, and various breathing and orofacial dysfunction. Passionate about education and self-help, she published Accomplished: How to Sleep Better, Eliminate Burnout and Execute Goals. When not working with clients globally, she spends time with her husband and four kids.