Linda D’Onofrio writes about frenectomy and the options pre- and post-treatment that can affect long-term success.

by Linda D’Onofrio, MS, CCC-SLP

by Linda D’Onofrio, MS, CCC-SLP

For many providers the correlation between sleep disorders and ankyloglossia feels like a fad. But for providers like myself who have been diagnosing and treating pediatric and adult oromyofunctional disorders for decades, it is an evidence-based understanding of anatomy and physiology. This article will cover my approach to diagnosis and treatment in frenectomy patients three years and older.

I take calls regularly from potential adult patients asking to get on my caseload because they want a lingual frenectomy, and their doctor said they need to do some tongue stretches or something. They often balk when I tell them I need to conduct a full orofacial myofunctional evaluation before making recommendations for treatment, including frenectomy. Some of them tell me they found a bunch of exercises on YouTube, so they don’t understand why an evaluation is necessary. They’ve already been diagnosed with tongue tie. And I find myself saying the same thing again and again, because it’s true. Tongue tie is not your only problem and frenectomy is not your only answer.

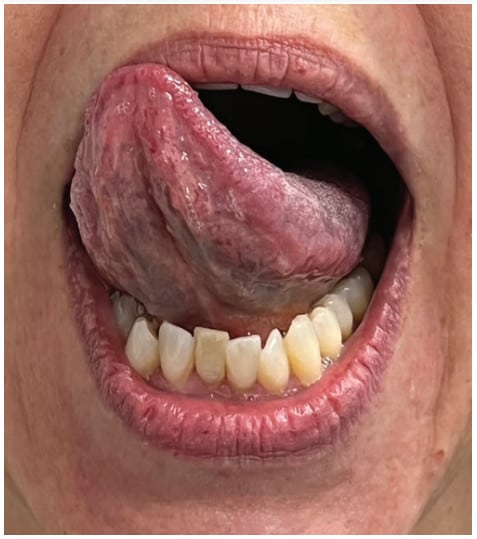

Ankyloglossia is a very critical structural symptom of an orofacial myofunctional disorder (OMD) that has the potential to change other craniofacial structures, change muscular development, make some foods unsafe or unpleasant, change how we speak, and cause thousands of dollars of orthodontic damage.3 As critical as this one symptom is, a restricted lingual frenulum is one of over a dozen structural and functional symptoms of an OMD. For those who treat sleep disordered breathing (SDB), this is a critical but new understanding. “Orofacial myofunctional disorders can serve as clinical markers for SDB and include the following structural and functional symptoms: enlarged tonsils; elongated uvula; narrow maxillary arch; tongue scalloping; restricted lingual frenum; orofacial pain with or without headache; interdentalized speech sounds (/s, z, t, d, n, l/); abnormal swallow patterns; impaired chewing; and picky eating.”1

Correcting the lingual structure, through frenectomy or frenuloplasty, does not normalize lingual function. It won’t normalize the swallow or change breathing. It won’t end picky eating and it won’t resolve sleep apnea. It is generally accepted that surgeries impacting skeletal muscles require rehabilitation afterwards, and that includes the face and mouth. Rehabilitation ensures wound healing only, it does not teach normal function. That is the goal of oromyofunctional therapy (OMT).

An OMD evaluation is an assessment of bony and soft tissue structure, including oral restrictions. It is an assessment of facial and oral function when at rest and sleeping, when swallowing, and when communicating. If performed by a speech-language pathologist, it will include a feeding, voice, and a speech sound assessment. Evaluation of lingual coordination and range of motion, especially the posterior tongue’s ability to elevate away from the mandible and fit comfortably in the posterior palate, is critical for sleep breathing.

Effective and efficient OMT, including pre and post lingual frenectomy care, is dependent on a differential diagnosis and individualized treatment planning. Most patients want to get off CPAP – or better tolerate it, and reduce the triggers that interrupt good quality sleep.

My pre/post frenectomy routine is something that any three-year old can learn and every parent can understand. The patient must participate in their own post-procedural care. Developing that ability might take three sessions for one patient and ten for another. My experience preparing children and adults for this procedure for twenty years has been that what a patient does before the frenectomy is exactly what they will do afterwards. Surgery on a patient that is not ready increases the likelihood of a less than optimal outcome and the need for a secondary procedure. Timing is everything.

Even in infants, the timing of lingual frenectomy is critical to immediate and long-term success. Timing of lingual frenectomy, palatal expansion, and other oral interventions is its own topic).4 The timing of lingual frenectomy with maxillary-mandibular advancement surgeries is not generally agreed upon and does not have a robust research base.

The routine below is part of my diagnostic process; it is what I teach patients that may not want frenectomy, it is what I teach before referral, and it’s what I teach to my many patients who had frenectomy in the past. Some of my patients are so restricted, they can barely manage this routine, so it is more important for them to intellectually understand normal function prior to referral. I break things down into five activities, exercises, strategies, techniques, postures – whatever term fits your schema.

Basic Pre/Post Frenectomy Lingual Range of Motion Objectives

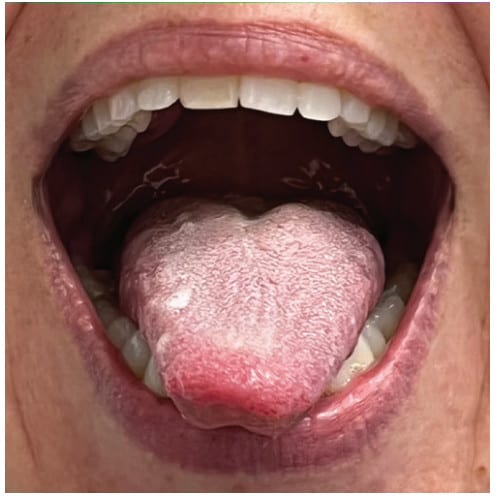

- Unsupported stable extension. I call it a “diving board” since many of my restricted patients have more of a “water slide” presentation. The mouth needs to be open, and the lips and teeth should not support the tongue blade. This posture requires stability and balance of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue. This can be initially tricky if the tongue is flaccid or maintains a wide posture in the

- Extended lateralization with an open stable mandible. I refer to this simply as “side to side” and with children I often teach this with a preferred flavor in the corners of the mouth. The goal is that the tongue moves independently from the mandible. This task, when slowed down, can support extension.

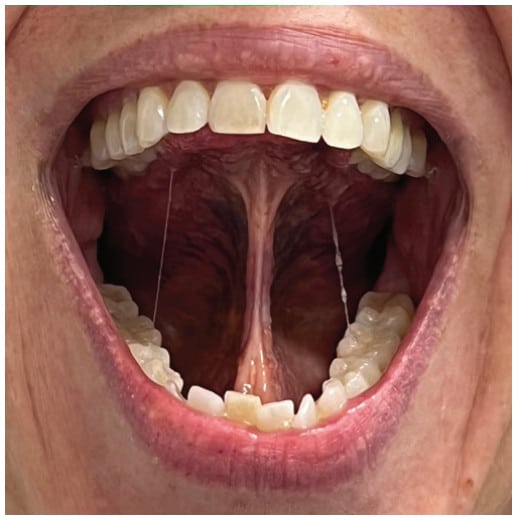

- Elevation to the rugae/alveolar ridge with open jaw and (in my clinic) elevated posterior retraction with open jaw. In speech, these are essentially the sounds /el/ and /ar/ in the American English dialect. The anterior elevation is both a diagnostic and therapeutic task for anterior restriction. The second posture I highly recommend, since a large segment those with posterior tongue tie languish for years in school speech therapy without proper diagnosis or treatment.

- Circumlocution around lips, around teeth, and around the cheeks. Cleaning and clearing the oral space are the primary functions of the tongue after a safe swallow. In an exercise program, I would refer to circles around lips (always with an open jaw), circles around the outsides of the teeth (with a big smile) and sweeping the vestibules and sulci. Even when cleaning inside a molar, I encourage circular motions rather than sweeping ones to engage the intrinsic muscles of the

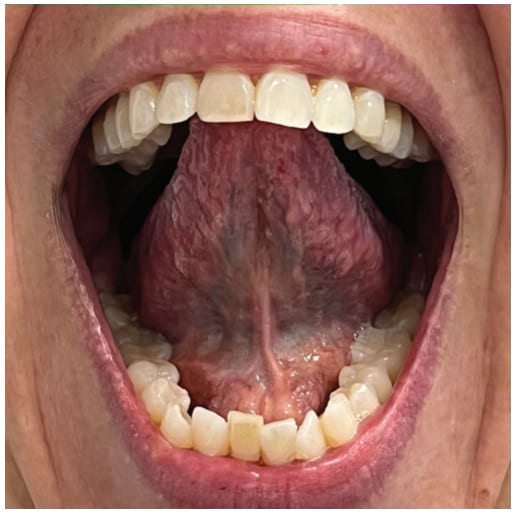

- Full-blade lingual-palatal suction with wide open jaw. If you only perform one task, this should be it, as it engages many lingual and facial muscles and is the exercise that it critical to generalizing stable saliva swallows. Teaching this task can be tricky for some and depends on craniofacial shape, jaw alignment, maxillary height, tori, degree of bruxing or lack of molar eruption. Function and structure depend on each other.

I’ve seen various recommendations on the time and length of treatment. My clinical experience has been that a few minutes of engaging in these activities 3-5 times per day, for a minimum of a month post procedure results in optimal healing and significantly improved, if not normalized range of motion. I measure this several ways. Objectively, I assess pre and post treatment measurements for maximum mouth opening, open with elevated lingual tip, and open with full lingual-palatal suction. I am looking for as close to a 1:1:1 ratio as is appropriate for that patient. But I am re-assessing much more, including breathing, and swallowing at rest, during sleep, and during meals. I may have other feeding, chewing, articulation, or voice objectives. My work is often aligned with other medical and dental providers, so my success is measured by how efficiently and effectively my team members meet their goals. And most importantly, my outcomes are considered successful when my patient is satisfied, and their health has improved in a measurable way.

Considerations for Individualized Treatment Planning

- To keep it simple for small children, I tell them their tongue can go out, it can go side to side, it can go up and down, it can go round and round, and it can suction to the roof of our mouth. (It can do so much more, but this is just for rehab.)

- To keep it functional for the many children with neurocognitive differences, much of this routine can be accomplished effectively with a peanut butter and jam sandwich and a glass of chocolate milk. I always sit side by side in a mirror (or on zoom) with my patients so we can see ourselves and each other.

- To keep it relevant for adults, I show how these tasks are related to normal muscle function that reduces or eliminates apnea triggers, helps with the mastication of foods, and improve speech clarity. I use language that they can relate to and connect strategies to their personal objectives.

- My more mature patients get excited when I explain that these exercises tone the face and neck, make eating denser foods more enjoyable, and they are much cheaper and more effective than fillers for maintaining a youthful face.

All medical and dental providers need to screen and refer for ankyloglossia if they do not diagnose and treat it themselves. Validated protocols for diagnosing ankyloglossia include the Marchesan Lingual Frenulum Protocol for children and adults from 2012,5 the Lingual Frenulum Protocol for Infants, updated in 2019,2 and the FAIREST 6 for children and adults.6 Multidisciplinary intervention of anatomical and physiological dysfunction should be the gold standard of care. Structural providers, including sleep dentistry and orthodontics, should collaborate with oromyofunctional providers like speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and specially trained dental hygienists to address the underlying causes of dysfunction and maximize patient outcomes.

Functional frenectomy is the topic of this article that utilizes a CO2 laser. Read “Functional Frenectomy (Osteopathically Guided)” here: https://dentalsleeppractice.com/functional-frenectomy-osteopathically-guided/

- Archambault, N., Healthy Breathing ‘Round the Clock. ASHA Leader 2018 Feb 1. https://leader.pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/leader.FTR1.23022018.48

- Campanha SMA, Martinelli RLC, Palhares DB. Association between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Codas. 2019 Feb 25;31(1):e20170264. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20182018264. PMID: 30810632. https://www.scielo.br/j/codas/a/bxq8mdhZ

wXvnxkxCCyyBHGf/?lang=en - D’Onofrio, L., Oral dysfunction as a cause of malocclusion. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2019;22(Suppl. 1):43-48. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ocr.12277

- D’Onofrio, L., Coordinating orthodontics, oral surgery, OSA and oromyofunctional therapy. The Orofacial Myofunctional Lecture Series, 2020 July; Vimeo online. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/orthooralsurgosaandomt

- Marchesan IQ. Lingual frenulum protocol. Int J Orofacial Myology. 2012 Nov;38:89-103. PMID: 23367525. https://ijom.iaom.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1063&context=journal

- Oh, Zaghi, et al. Determinants of Sleep-Disordered Breathing During the Mixed Dentition: Development of a Functional Airway Evaluation Screening Tool (FAIREST-6). Pediatr Dent. 2021 Jul 15;43(4):262-272. https://www.fairest.org/tools/

Linda D’Onofrio, MS, CCC-SLP, has a private practice in Portland, Oregon focusing in craniofacial disorders, oromyofunctional disorders, feeding disorders and dysphagia, and sensory-motor speech disorders. She completed her Masters at the University of Oregon, her medical externship at the Oregon Health Sciences University Medical Center with a focus on inpatient neurological acute care and outpatient cognitive rehabilitation, and she completed her clinical fellowship at the Oregon VA Medical Center with a focus on dysphagia, aphasia, brain injury, and oral cancer. In 2019, Linda published in the journal Orthodontics & Craniofacial Research, and she was awarded the most downloaded article for the journal that year. She participates on a local craniofacial team and on a local sleep neurology team, and she has reviewed manuscripts for the Journal of Oral Rehabilitation and Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. She is a member of the American Speech-Language Hearing Association, a past president of the Oregon Speech-Language Hearing Association, and she has lectured on oral physiology at several dental and orthodontic programs, including Stanford, Tufts, and the Vienna School for Interdisciplinary Dentistry.

Linda D’Onofrio, MS, CCC-SLP, has a private practice in Portland, Oregon focusing in craniofacial disorders, oromyofunctional disorders, feeding disorders and dysphagia, and sensory-motor speech disorders. She completed her Masters at the University of Oregon, her medical externship at the Oregon Health Sciences University Medical Center with a focus on inpatient neurological acute care and outpatient cognitive rehabilitation, and she completed her clinical fellowship at the Oregon VA Medical Center with a focus on dysphagia, aphasia, brain injury, and oral cancer. In 2019, Linda published in the journal Orthodontics & Craniofacial Research, and she was awarded the most downloaded article for the journal that year. She participates on a local craniofacial team and on a local sleep neurology team, and she has reviewed manuscripts for the Journal of Oral Rehabilitation and Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. She is a member of the American Speech-Language Hearing Association, a past president of the Oregon Speech-Language Hearing Association, and she has lectured on oral physiology at several dental and orthodontic programs, including Stanford, Tufts, and the Vienna School for Interdisciplinary Dentistry.