Mood disorders and sleep are often inseparable. Find out from Colonel Scott Williams, MD, FAASM, how some psychiatric conditions affect sleep.

by Colonel Scott Williams, MD, FAASM

by Colonel Scott Williams, MD, FAASM

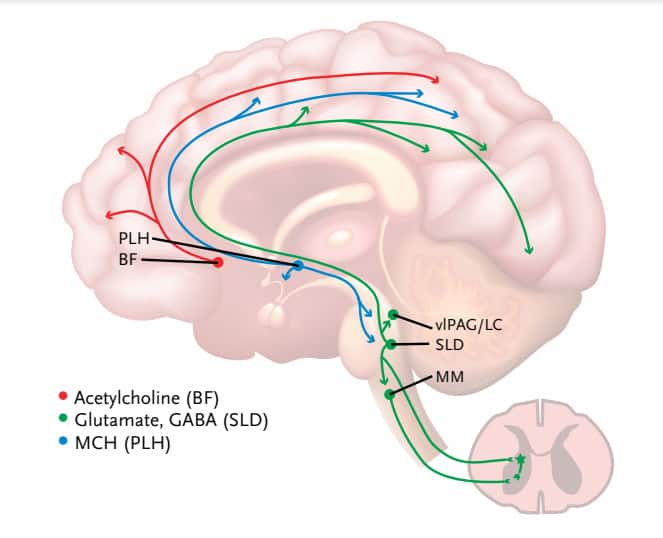

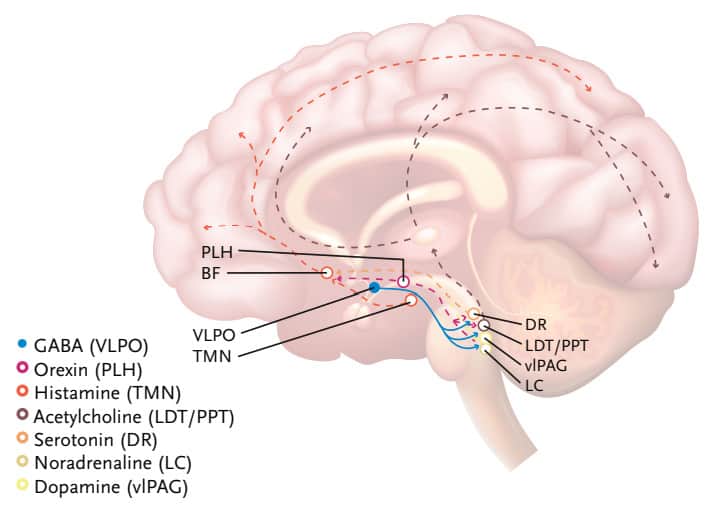

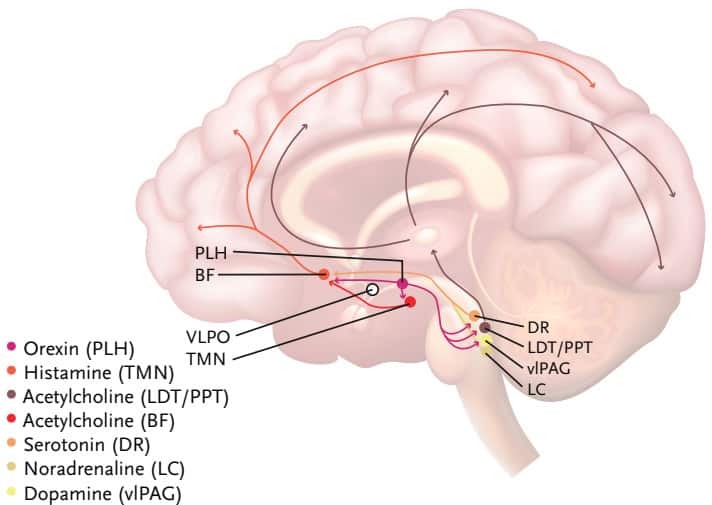

Sleep and mental health are inextricably linked, and there is a large volume of evidence looking at the various relationships across disease states. While it is impractical to provide an exhaustive review of the literature here, this article will focus on a few of the more common psychiatric diagnoses and how they both impact and are impacted by sleep. As we know, there are three states of being. We are either awake, in Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep, or we are in REM sleep.1 There are a variety of neurotransmitters that affect both wake and sleep (Figures 1-3) and it is no coincidence that many of these neurotransmitters are the same ones affected by psychiatric disorders.2

Psychiatric conditions can change the relative percentage of time during a 24 hour period that we are in these three states, and in so doing, markedly impact the subjective experience of the patient. In contrast, treatment of psychiatric conditions may also change the proportion of time spent in each state in a way that is different than those who are in remission.

How Does Depression Affect Sleep?

Impaired sleep is a hallmark feature of depression and is a diagnostic criterion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.3 It is estimated that 20-30% of patients suffering from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) have difficulty falling or staying asleep.4,5 In addition, those with depression have been observed to have decreased REM latency.6 In contrast, serotonergic medications such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) prolong REM latency to a greater extent than is seen in those without depression.7 This can be understood when looking once again at the CNS neurotransmitters and their impact on the various states of being (Figure 2: REM on and REM off neurons).

Some antidepressants may also worsen sleep disorders such as insomnia. Bupropion, for example, is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (DNRI). There are different formulations of bupropion, and the shorter acting formulation, when taken too close to bedtime, may increase overall sleep latency.8

While antidepressants have shown clear benefit in reducing many of the sequelae of depression, it is less clear whether the change in REM latency has a direct impact on overall subjective sleep quality and few studies have directly linked SSRI use with sleep improvement.9 It is also unclear whether psychotherapy, which in itself does not alter REM latency other than to return it to the premorbid state, has a differential impact on sleep when compared with medication management.

How Do Sleep Disorders Affect Depression?

It can be difficult to determine the cause-effect relationship between sleep and depression because there is often a vicious cycle whereby one condition worsens the other. In some patients without a history of depression, there is data showing that the development of a sleep disorder may increase the risk of subsequent depression. Just as many depressed individuals endorse insomnia, insomnia itself is a risk factor for the development of depression with an overall odds ratio of 2.1.10 One of the most common sleep disorders, Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), causes profound sleep fragmentation and has been shown to increase the risk of subsequent MDD.11 There is scant data regarding the impact of OSA treatment on depression, however. The few studies that have been conducted have shown a benefit with CPAP. El-Sherbini and colleagues found in a small population that the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores pre and post CPAP were significantly different.12

There is even less data assessing the impact of mandibular advancement device (MAD) therapy in patients with OSA-induced depression, and there are no high-quality data discussing the relative impact of CPAP vs. MAD on depression.13 This is a critical gap in the literature and is deserving of significant attention.

While neurophysiology and the interplay between psychiatry and sleep is complex, there are a few basic tenets that must be understood. First, each patient must be treated holistically. Second, it is important to treat these conditions in parallel, not in series.

How Does Bipolar Disorder Affect Sleep?

Bipolar disorder is a mental disorder characterized by shifts between depression and overly energetic, irritable or impulsive moods.2 The impact of bipolar depression on sleep quantity is largely the same as unipolar depression, but bipolar mania reduces sleep in a different way. Whereas in depression, patients often feel fatigued but have trouble transitioning to sleep, in hypomania or mania, patients lack the desire or need for sleep.1 During manic episodes, patients may not be aware that they are lacking the restorative properties of sleep. There are studies showing that toxic proteins can accumulate in patients with bipolar disorder, leading to neurodegeneration, and the cyclic lack of sleep may be a key part of this pathology.14 Treatment of bipolar disorder may slow this neurodegeneration, but currently there is little evidence to show the absolute magnitude of the benefit.

Conclusion

While neurophysiology and the interplay between psychiatry and sleep is complex, there are a few basic tenets that must be understood. First, each patient must be treated holistically. Do not assume that treatment of one condition will completely treat another. Co-morbid sleep and psychiatric disorders must each be treated separately. Second, it is important to treat these conditions in parallel, not in series. Too often we see patients who are being treated for depression in the hopes that this will fix their chronic insomnia, or patients being treated for OSA in the hopes that this alone will allow their depression to remit. Each condition must be treated simultaneously, and once subjective and objective response is achieved, the treatment plan can be tapered.

For dental sleep practitioners especially, it is important to recognize the association between emotional reactivity and sleep disorders. One of the great advantages of dentistry over most medical clinics is the amount of time spent with a patient. If patients seem highly anxious, have a decreased tolerance for pain, or a heightened gag reflex, it is absolutely appropriate to ask about other areas of hyper-reactivity in their lives.

Images inspired by Bassetti et al, European Journal of Neurology, 2015, 22:1337-1354

Mood disorders can affect sleep, but so can a myriad of other health issues. Download Dental Sleep Practice’s “Patient Education Guide” to see what patients should know. https://dentalsleeppractice.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSP_PatientGuide2017_wm.pdf

- Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 6th Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Elsevier, 2016.

- Bassetti CL, et al. Neurology and psychiatry: waking up to opportunities of sleep. State of the art and clinical/research priorities for the next decade. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:1337-54.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th)

- Buysse DJ, Angst J, et al. Prevalence, course and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep 2008;31(4):473-80.

- Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Lemoine P. Comorbidity of mental and insomnia disorders in the general population. Compr Psychiatry 1998;39(4):185-97.

- Kupfer D, Foster FG. Interval between onset of sleep and rapid-eye-movement sleep as an indicator of depression. Lancet 1972;300:684-6.

- Chen C-N. Sleep, depression and antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:385-402.

- Gandotra K, Jaskiw GE, Williams SG, et al. Development of insomnia associated with different formulations of bupropion. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2021;23(1):20br02621.

- Everitt H, Baldwin DS, Stuart B, et al. Antidepressants for insomnia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;5(5):CD010753.

- Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord 2011;135(1-3):10-9.

- Harris M, Glozier N, Ratnavadivel R, Grunstein RR. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:437–44.

- El-Sherbini AM, Bediwy AS, El-Mitwalli A. Association between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and depression and the effect of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 2011.

- Povitz M, Bolo CE, Heitman SJ, et al. Effect of treatment of obstructive sleep apnea on depressive symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014,11(11):e1001762.

- Naserkhaki R, Zamanzadeh S, Baharvand H, et al. cis pT231-Tau drives neurodegeneration in bipolar disorder. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019;10(3):1214-21

Colonel Scott Williams, MD, FAASM, is the director for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. LTC Williams was born in Bournemouth, England and was raised in Princeton, New Jersey. He graduated and was commissioned into the U.S. Army from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2000. LTC Williams received his medical doctorate from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in 2004. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Psychiatry at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 2009. He completed fellowship training in Sleep Disorders Medicine at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in 2012. Upon graduation from fellowship, Dr. Williams assumed duties as Chief of Sleep Medicine at Womack Army Medical Center. While there he served on the AASM Education Committee and obtained an academic appointment as assistant professor of medicine at USUHS, later rising to the rank of associate professor of Medicine (primary) and Psychiatry (secondary). He increased his involvement with the AASM after returning to WRNMMC to take charge of the Sleep Disorders Center. He is now the chair of the Sleep Technologist and Respiratory Therapist Education Committee and is part of the gold standard panel for the Inter-Scorer Reliability program.

Colonel Scott Williams, MD, FAASM, is the director for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. LTC Williams was born in Bournemouth, England and was raised in Princeton, New Jersey. He graduated and was commissioned into the U.S. Army from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2000. LTC Williams received his medical doctorate from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in 2004. He completed a dual residency in Internal Medicine and Psychiatry at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in 2009. He completed fellowship training in Sleep Disorders Medicine at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in 2012. Upon graduation from fellowship, Dr. Williams assumed duties as Chief of Sleep Medicine at Womack Army Medical Center. While there he served on the AASM Education Committee and obtained an academic appointment as assistant professor of medicine at USUHS, later rising to the rank of associate professor of Medicine (primary) and Psychiatry (secondary). He increased his involvement with the AASM after returning to WRNMMC to take charge of the Sleep Disorders Center. He is now the chair of the Sleep Technologist and Respiratory Therapist Education Committee and is part of the gold standard panel for the Inter-Scorer Reliability program.