If your patient has a history of concussion or head trauma, it’s time to have a discussion about breathing disorders or OSA. Read this article about “the breathing brain.”

by Cynthia Stein, PT, MEd, and Karen Parker Davidson, DHA, MSA, MEd, MSN, ARPN

by Cynthia Stein, PT, MEd, and Karen Parker Davidson, DHA, MSA, MEd, MSN, ARPN

If you are a sports connoisseur and watch the news often, the numerous injuries resulting in a concussion are overwhelming and may catch your attention. More than 3 million concussions occur annually with approximately 1.7 million concussions among kids where nearly 20% are sports related, more often in girls than boys.1 Based on the prevalence statistics, concussive care is finding its way into many medical, dental, and ancillary practices such as chiropractic and physical therapy. Many clinicians may not have recognized the connection to breathing, especially in the dental chair.2 The common denominator among these specialties and the injury is the breathing brain. How does the practitioner address this type of injury in their practice, and how is it identified? Major concerns in recent years are the longitudinal effect of concussion on health, such as vestibular changes, the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and sleep apnea.3

A concussion impacts the “breathing brain” by a potential disruption in coordination between the brain and lungs because the brain cannot function as it did prior to the injury. The result is breathing disturbances with symptoms of fatigue, dizziness, and shortness of breath. Furthermore, breathing problems may be misidentified as sleep disordered breathing problems (SDBP), headaches, daytime fatigue, or exercise intolerance. The respiratory issues from post-concussion syndrome (PCS) may linger for months or years after the initial injury before diagnosis. A thorough history in the dentist’s office with a patient suspected as having SDBP should include concussion.

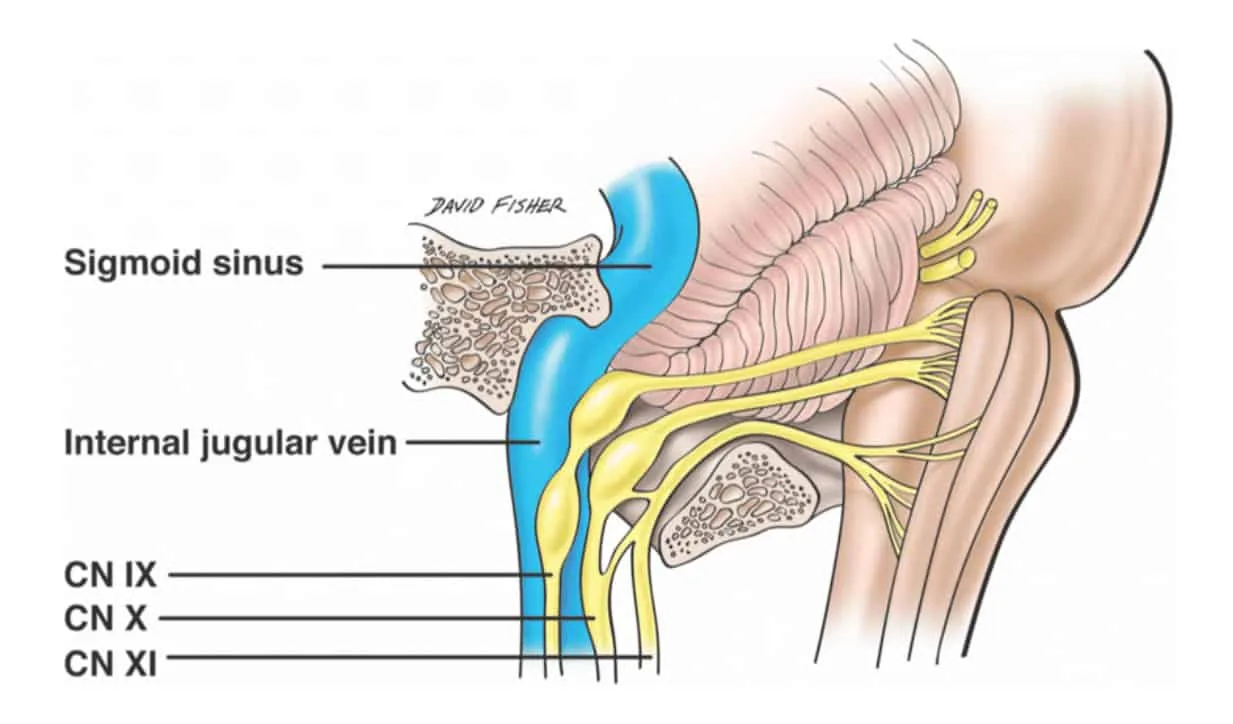

When there is any form of blunt trauma to the head, the bones of the skull become jammed. These bones fit together like a puzzle. The sphenoid and occipital bone articulate with each other to form the sphenobasilar joint. The temporal bone articulates with the occipital bone to form the jugular foramen. This foramen is where the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), the vagus nerve (X), spinal accessory nerve (XI), and jugular vein exit from the brainstem (Figure 1). Because trauma shifts these bones, it affects nervous and vascular transmission. The vagus nerve is a part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). This nerve is the major sensory pathway from the lungs to the brain. It controls pulmonary function and it regulates respiration, including normal breathing and respiratory defense mechanisms, and also provides sensory feedback from the lungs to the brain. This is why breathing has to be measured and addressed in treating Post Concussion Syndrome.

As part of the care plan, predictive models in symptom recovery using artificial intelligence (AI) have been discussed and researched. Newer modalities for assessment and treatment should be considered in making clinical predictions and separated from the potential misdiagnoses mentioned above.4 The role of physical therapy (PT) is outlined in concussive care that further accentuates the collaborative relationship with dentistry beyond the posture and positional aspects of SDBP.5

Oleski et al. (2002) examined motility of the cranium on x-rays post cranial vault manipulation. The findings showed 91.6% of patients had documented cranial bone movement differences in measurement at 3 or more sites on the radiographs.6 This type of manipulation connects to Nasal Release Technique (NRT). NRT, developed by Dr. J. R. Stober of Portland, OR in the 1930s, has many other names, such as nasal specific technique, cranial facial release, endonasal technique, and neurocranial restructuring. The procedure is one aspect of concussion care and is done by inserting a finger cot attached to a blood pressure bulb into the 3 nasal meatuses. The balloon is quickly inflated and deflated which is said to adjust the bones of the skull. NRT is commonly used by physical therapists and chiropractors to mobilize the bones of the skull after concussion, for sinus problems, and treating headaches. Dentists use it prior to oral expansion therapies.

Mystery and skepticism surround the efficacy of NRT and the impact of breathing in the post concussive patient because this has never been researched. In the first of its kind study, an analysis of data from transnasal pressure changes, nasal flow limitations, and vestibular changes in 9 concussion patients was conducted to find a correlation between the measurement variables and NRT. Each participant had three measurements done pre and post NRT: transnasal pressure changes/nasal resistance with 4-phase rhinomanometry (GM Instruments, Ltd.), nasal patency and flow limitations measured and Peak Nasal Inspiratory Flow (PNIF) meter (GM Instruments, Ltd.), and vestibular changes measured with eye tracking technology (RightEye, LLC). The mean age was 36.9 with 45% male, 21.5% female. The results found 8 of the 9 patients, or 88%, had a 55% decrease in inspiratory mean resistance (1.27-0.57 Pa/cm3/s) and a 26% decrease in expiratory mean resistance (0.98-0.72 ro Pa/cm3/s). and a 24% increase in inspiratory flow (102- 126 L/min). Seventy-five percent of the cohort had vestibular changes. Patient #7, who had an increase in transnasal pressure changes was identified as having a histamine reaction to latex. The results provide preliminary evidence that NRT can increase nasal flow and decrease nasal resistance. In postnasal release testing, Martha Cortes, DDS, also found a correlation between sleep apnea and transnasal pressure changes in the concussion patient with 4-phase rhinomanometry, in addition to the vestibular changes seen in patients with OSA. The study is in peer review for publication.

Based on the study outcomes, it is recommended that airway dentists ask patients if they have a history of concussions or concussive events if they suspect them of breathing disorders or OSA.

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank Martha Cortes, DDS, and Jennifer Hobson DPT, MTC, CFC, CMTPT, OMT of the Hobson Institute for their valuable contributions to the study.

Brain health and concussion are just a couple of the topics to discuss with patients. Maintaining brain health starts as early as childhood. Read this interesting article, “Can Dementia Begin in Childhood?” to find out about early risk factors and intervention. https://dentalsleeppractice.com/can-dementia-begin-in-childhood/

- Kosoy J, Feinstein R. Evaluation and Management of Concussion in Young Athletes. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2018;48(5-6):139-150.

- Jackson WT, Starling AJ. Concussion Evaluation and Management. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(2):251-261.

- Santos A, Walsh H, Anssari N, Ferreira I, Tartaglia MC. Post-Concussion Syndrome and Sleep Apnea: A Retrospective Study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):691.

- Fleck DE, Ernest N, Asch R, et al. Predicting Post-Concussion Symptom Recovery in Adolescents Using a Novel Artificial Intelligence. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(7):830-836.

- Concussive Events: Using the Evidence to Guide Physical Therapist Practice. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(4):176-177.

- Oleski SL, Smith GH, Crow WT. Radiographic evidence of cranial bone mobility. Cranio. 2002;20(1):34-38.

- Lower Cranial Nerve Syndromes: A Review – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Anterolateral-view-of-the-contents-of-the-right-jugular-foramen_fig1_342773452 [accessed 3 Jan, 2023]

Cynthia Stein, PT, MEd, is a physical therapist and tireless educator. She served as a commissioned officer in the US Navy as a staff physical therapist at Annapolis Naval Hospital and later as chief physical therapist at Philadelphia Naval Hospital. She owned and operated Squirrel Hill Physical Therapy for 30 years in Pittsburgh,Pa. During this time, she attended extensive training on methods for treating concussion that included standard vestibular rehab and alternative methods. As the founder of Conquer Concussion, she has taken her expertise on the road and long distant learning platforms teaching her proprietary Nasal Release Technique around the world to numerous medical and dental providers over the past 8 years. She graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a B.S. in Physical Therapy and Temple University with a Masters in Education.

Cynthia Stein, PT, MEd, is a physical therapist and tireless educator. She served as a commissioned officer in the US Navy as a staff physical therapist at Annapolis Naval Hospital and later as chief physical therapist at Philadelphia Naval Hospital. She owned and operated Squirrel Hill Physical Therapy for 30 years in Pittsburgh,Pa. During this time, she attended extensive training on methods for treating concussion that included standard vestibular rehab and alternative methods. As the founder of Conquer Concussion, she has taken her expertise on the road and long distant learning platforms teaching her proprietary Nasal Release Technique around the world to numerous medical and dental providers over the past 8 years. She graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with a B.S. in Physical Therapy and Temple University with a Masters in Education. Karen Parker Davidson, DHA, MSA, MEd, MSN, ARPN, for over two decades has held many positions in the medical device industry in the ENT and Sleep markets, in addition to thirty years of clinical experience to include service as a Critical Care Nurse and Flight Nurse in the US Air Force Reserves. Dr. Davidson is adjunct faculty at Liberty University and Central Michigan University, founder of FACT Healthcare Consulting Group, and creator of the patent pending DAFNE Score System to guide and educate healthcare providers the values of objective nasal function and treatment options and improvements based on the readings. She is published in medical journals discussing airway disorders, a coauthor of “The Power of the Tongue In the Beginning, We Were All Tongue Tie” and “Sleep Apnea and Pregnancy: The Female Response to Sleep Breathing Disorders”, a contributing author to “Growing Into Breathing Problems: The Quest for Collaborative Life Time Solutions” and “Health Informatics and Patient Safety in Times of Crisis”, and the author of an upcoming book for release this year, “Breathe Through Your Nose, Don’t Pay Through It: The Impact the Healthcare Industry has on Nasal Function and How We Breathe”.

Karen Parker Davidson, DHA, MSA, MEd, MSN, ARPN, for over two decades has held many positions in the medical device industry in the ENT and Sleep markets, in addition to thirty years of clinical experience to include service as a Critical Care Nurse and Flight Nurse in the US Air Force Reserves. Dr. Davidson is adjunct faculty at Liberty University and Central Michigan University, founder of FACT Healthcare Consulting Group, and creator of the patent pending DAFNE Score System to guide and educate healthcare providers the values of objective nasal function and treatment options and improvements based on the readings. She is published in medical journals discussing airway disorders, a coauthor of “The Power of the Tongue In the Beginning, We Were All Tongue Tie” and “Sleep Apnea and Pregnancy: The Female Response to Sleep Breathing Disorders”, a contributing author to “Growing Into Breathing Problems: The Quest for Collaborative Life Time Solutions” and “Health Informatics and Patient Safety in Times of Crisis”, and the author of an upcoming book for release this year, “Breathe Through Your Nose, Don’t Pay Through It: The Impact the Healthcare Industry has on Nasal Function and How We Breathe”.