by Drs. Michael S. Simmons and Colin M. Shapiro

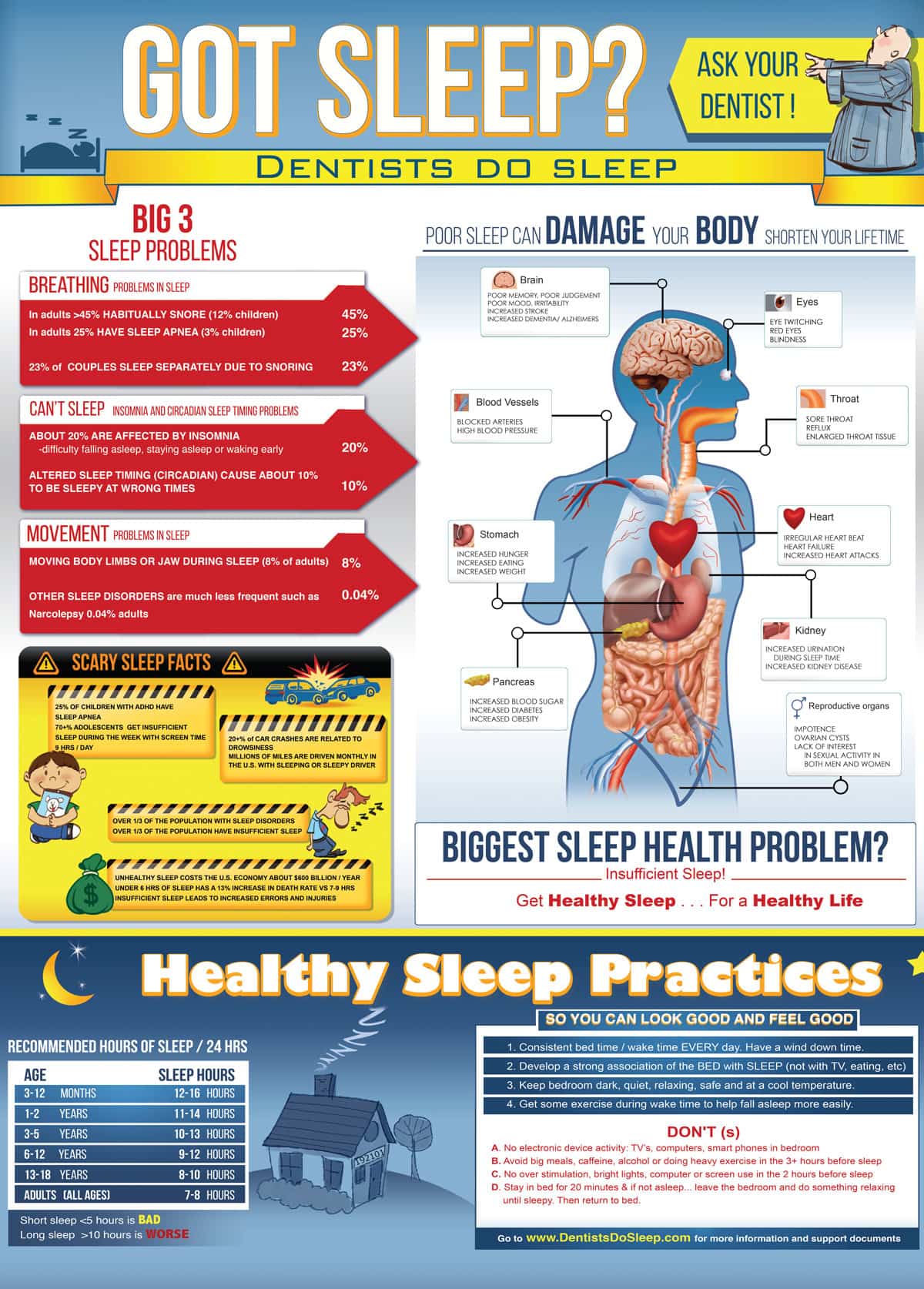

Population level sleep disorders and sleep deprivation were reported by the Institute of Medicine in 2006 to be an “enormous unmet public health need”1. Sleep, like nutrition and physical activity, is a critical determinant of health and well-being1. Now, a dozen years after this landmark report, there is strong indication of further decline in healthy sleep in our communities. Studies indicate inadequate sleep has increased in industrialized populations to between 33-45% of adults2,3,4 and poor sleep quality starts as early as 3 years old, due to issues such as screen time5. Population level unhealthy sleep has resulted in substantial economic and health costs approaching $600 billion/year in the U.S. alone as of 20176 and this figure does not include the childhood age group.

The iconic sleep textbook’s opening chapter7 states “from today’s vantage point, the greatest challenge for the future is the cost-effective expansion of sleep medicine to provide benefit to the increasing number of patients in society.” While healthy sleep, along with healthy diet and exercise contribute to longevity and quality of life, the general lack of education about healthy sleep continues to be prevalent and most concerning in healthcare providers8,9. Uninformed health providers contribute to poor guidance for the public, who may view snoring as normal, unrestful sleep as unavoidable, and self-imposed sleep deprivation as a badge of honor.

Population based health problems require population-based solutions! One pragmatic answer to resolving population-based sleep health problems is to identify resources and remove barriers that limit access to care. In the case of sleep health there are two main issues at hand: sleep disorders affecting about 1/3 of the population and unhealthy sleep behaviors affecting a further 1/3 of the population. Many people have both issues. Conservatively 100+ million are affected by unhealthy sleep in the U.S and >12 million in Canada. Identifying sleep disorders is important and the vast majority with sleep disorders fall into three readily diagnosable ICSD-3 categories10: sleep related breathing disorders (SRBD), insomnia. and circadian rhythm disorders. Identifying poor sleep behaviors is also typically not too challenging and usually respond to sleep hygiene coaching and cognitive behavioral therapy. The rub in all this is the counterproductive bottleneck to diagnosis and the lack of primary care in addressing these simple and readily identifiable presentations of unhealthy sleep.

Early diagnosis and multiple portals of entry into the healthcare system are one obvious answer. The other is population-based education and practice of best sleep health behaviors. Sleep physicians, numbering about 6,00011 hail from a variety of primary specialties and should act in the capacity of quarterbacks, like the cardiologist specialist in cardiovascular health, to address the more complex and challenging presentations. The approximate 850,000 U.S. physicians are typically untrained in sleep disorders12 and are often overwhelmed with their current practice of problem-based care, hard-pressed to add sleep disorders assessment. Pediatricians, otolarngologists and mental health providers, who frequently see sleep disorder presentations, could add about 15,000 doctors to the 6,000 sleep physicians but would still leave an enormous healthcare gap with less than 25,000 to manage well over 100,000,000 potential patients. This is where dentists and others in primary care can significantly help to close the gap. Dentists, like family physicians and, in some jurisdictions, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and chiropractors, are primary health care providers, licensed to diagnose and work unsupervised. In the U.S., dentists number just over 190,000. So if 1/3 of all dentists could engage in providing primary sleep healthcare, it would more than triple the currently available primary sleep health providers. Other primary healthcare providers could also supplement this workforce to increase the number of patients diagnosed with sleep disorders.

This all sounds fine until the process of engaging patients into care is explored. The current bottleneck is in diagnosing SRBD, insomnia or circadian problems as if it is some difficult diagnostic sequence or process. On the contrary, diagnosing the majority of these sleep disorders is most often quite simple with a concerted sleep focused history and, if indicated, sleep testing,13 which can be mostly done at home and interpreted remotely by a boarded sleep physician. While screening is sometimes used as a wide net to catch potential sleep disorders, positive results merely indicate the need for a sleep history, associated exam, and potential sleep studies that are required for diagnosis. Some professionals identify sleep disorders as a “medical problem” outside the scope of practice of dentistry and others opine family physicians would not be interested. The consequences of “mis-diagnosis” are logarithmically shy in population health impact when compared to the currently existing “missed diagnosis.” In this context it should be noted that there was a time when only cardiologists measured blood pressure and while many others now treat cardiovascular disease, cardiologists have become substantially busier.

Diagnostic pathways are rapidly changing with the development of technology, using tools that will be equivalent to and in some ways more appropriate than sleep studies in lab. In her 2017 annual report, the President of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine noted11 that patients “are monitoring and tracking their own sleep in ways we never could have imagined 20 years ago”. Rather than have patients self-diagnose, health professional should be recruited, trained and engaged. The obvious first answer is dentists, who may diagnose and treat other life threatening “medical” disorders such as oral cancer, nicotine addiction, bulimia, and obesity. Dental professionals are highly trained in the anatomy and physiology of the oral cavity and associated structures, preventive and health maintenance therapies, and are an underutilized systemic healthcare provider.

Diagnostic pathways are rapidly changing with the development of technology, using tools that will be equivalent to and in some ways more appropriate than sleep studies in lab. In her 2017 annual report, the President of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine noted11 that patients “are monitoring and tracking their own sleep in ways we never could have imagined 20 years ago”. Rather than have patients self-diagnose, health professional should be recruited, trained and engaged. The obvious first answer is dentists, who may diagnose and treat other life threatening “medical” disorders such as oral cancer, nicotine addiction, bulimia, and obesity. Dental professionals are highly trained in the anatomy and physiology of the oral cavity and associated structures, preventive and health maintenance therapies, and are an underutilized systemic healthcare provider.

While dentists may be pigeonholed to periodontal disease, “TMJ,” and tooth decay, they see more patients annually in health and disease than physicians who are problem-focused.

In the quest for public health solutions to unhealthy sleep, putting the diagnostic territorialism to rest is a worthy compromise. Training of doctor-level healthcare providers such as dentists initially, and then others, will help fill the gap in sleep health. Enabling patients to use quality devices for home recordings dispensed by a dentist, nurse, psychologist or family physician and interpreted by a sleep physician would be infinitely more desirable than allowing patients to self-diagnose and treat using a smart phone app presenting unvalidated data about their sleep. Moreover, the health profession guided process will help identify the more complex sleep disorder cases and get them to the expert sleep physicians / expert sleep dentists in a timely fashion. Currently these sleep experts are overwhelmed with the simple cases and lack availability to focus on the challenging cases that only they can manage. This is akin to limiting diagnosis and primary care of all patients with hypertension and high cholesterol to cardiologists. Clearly, we would witness in short time a drop off in care for the more challenging cardiomyopathies.

So, in this brave new world, the dentists and other members of the health professions are taught best practices in providing initial diagnosis of SRBD, insomnia and circadian problems along with provision of first line therapy as primary care providers for the simple cases, forwarding the more complex cases to the specialists. The diagnostic and treatment paradigms are developed, tested and upon proof of concept, these paradigms of care are duly instituted. Reimbursement to dentists is through medical billing, similar to other medical/dental crossover health issues such as headache and TMJ disorders that may or may not have medical coverage or have costs below high medical deductibles. When the value of care is recognized by patients, they often pay independent of insurance coverage. This is no different than cosmetic dental and medical care where patients pay out of pocket. In any event, insurance carriers must not discriminate against any healthcare provider diagnosing and delivering primary sleep health care simply to cost contain.

So, in this brave new world, the dentists and other members of the health professions are taught best practices in providing initial diagnosis of SRBD, insomnia and circadian problems along with provision of first line therapy as primary care providers for the simple cases, forwarding the more complex cases to the specialists. The diagnostic and treatment paradigms are developed, tested and upon proof of concept, these paradigms of care are duly instituted. Reimbursement to dentists is through medical billing, similar to other medical/dental crossover health issues such as headache and TMJ disorders that may or may not have medical coverage or have costs below high medical deductibles. When the value of care is recognized by patients, they often pay independent of insurance coverage. This is no different than cosmetic dental and medical care where patients pay out of pocket. In any event, insurance carriers must not discriminate against any healthcare provider diagnosing and delivering primary sleep health care simply to cost contain.

Einstein said “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them”. It’s time to recognize unhealthy sleep not just as a problem for the individual but rather as a public health problem. In the case of sleep health, dentists can definitely play a big part in the solutions.

For more insight on the public health problem of sleep deprivation and providing treatment for those who need it most, read “Sleep Medicine’s Seismic Shift to Dentists — Are You Ready?”