Despite the fact that orthodontic training programs have been teaching about growth and development ever since the beginning of the profession and the relationship between breathing behavior and facial growth has been written about for equally as long, once an orthodontist gets into practice much of that training gets set aside as an intellectual maxim but has very little influence on real-world diagnostics and treatment planning.

Despite the fact that orthodontic training programs have been teaching about growth and development ever since the beginning of the profession and the relationship between breathing behavior and facial growth has been written about for equally as long, once an orthodontist gets into practice much of that training gets set aside as an intellectual maxim but has very little influence on real-world diagnostics and treatment planning.

For example, when an orthodontist first sees a patient, the first thing we do is look at the teeth and describe the malocclusion by the Angle classification. I might describe a case to a colleague like this: “This 9-year-old girl comes in, Class II, 7mm overjet”. We can all imagine what that girl looks like from that simple description, right? Or I might say, “I had this div 2 case with an impacted canine” and any orthodontist can see the central incisors tipped back and the primary canine still in place with a bulge on the palate. And we can imagine a treatment plan that would go with that description as well.

In other words, the Angle Classification is not only the phenotype, it is also the diagnosis and the basis for the treatment plan. When a patient walks in the door and is described, classified, and planned this way, the underlying assumption is that her classification is a personal characteristic: a description of who this person is. Everything about this person is known from what can be seen at that moment in time, either clinically or through radiographs, and what is seen is all there is to be seen. It is a static way of looking at a patient. Static and simple and direct.

It also assumes that whatever this person presents with was this person’s destiny. Most often, malocclusion and facial deformity (called “skeletal patterns”) are written off to genetics and familial traits. If the child happens to look like one of the parents – even to the extent of having the same overlapping central incisors – then no further questions are asked: it’s a genetic trait. If both parents are beautiful with nice teeth and the kid looks a mess, then it’s either an uncle’s fault or it was a funny admixture of traits, ie: the Dad’s big teeth and the Mom’s small jaws. In any case, it was an outcome that could not have been avoided. This is who this person is.

Dynamic Thinking

There is a completely different way of thinking that has always been part of orthodontic pedagogy but is finally finding it’s way into clinical practice. The assumption in this model is that the way a patient presents herself in front of you now is NOT who they ARE but what they have BECOME…and are still becoming. That Class II with 7mm of overjet that you see in front if you is IN PROGRESS. And though there may be a genetic influence and familial traits involved, the actual malocclusion has almost NOTHING to do with genetics at all. In fact, what we have learned from the relatively new science of epigenetics is that most malocclusions in humans are actually a distortion of the genetic process triggered by some chronic stressor of the modern environment.

The anthropologists tell us that the “genetic” standard for the human dentition is room for 32 teeth in a wide arch. They say that because that’s the way it’s always been, up until the modern era anyway. Just as surely as a zebra has stripes, a pre-modern human has straight teeth with only minor exceptions. Anything other than that is a distortion – a compromise – of the ideal.

These distortions are the result of compensatory behaviors we make in response to the chronic stressors of the modern environment. The way we breathe, the way we eat, the way we sleep, the way we use our bodies have all changed in response to a very different way of life than the one our bodies were developed in. The mismatch between our genetics and the the modern environment is not only the origin of malocclusion but of all the chronic non-communicable diseases of modern life. This includes all the metabolic diseases (cardiac disease, diabetes, hypertension and obesity), all the immune diseases (autoimmune, inflammatory, cancer), behavioral issues (neurocognitive, autism, ADHD, addiction), and more. This also includes periodontal disease, caries, malocclusion, and importantly, breathing-disordered sleep (sleep disorders, flow limitation, Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome, and sleep apnea).

Dynamic Treatment

The prospect of the environment being the etiology of most chronic disease is somewhat overwhelming to practitioners who have been trained only to take care of the symptoms. CPAP, MADs, and even braces are merely ways to help a person compensate for the problem but do nothing to effect a cure (hence, lifetime retention and management). Changing from a static to a dynamic view of human biology not only requires a change in thinking, but a change in treatment approaches as well.

The prospect of the environment being the etiology of most chronic disease is somewhat overwhelming to practitioners who have been trained only to take care of the symptoms. CPAP, MADs, and even braces are merely ways to help a person compensate for the problem but do nothing to effect a cure (hence, lifetime retention and management). Changing from a static to a dynamic view of human biology not only requires a change in thinking, but a change in treatment approaches as well.

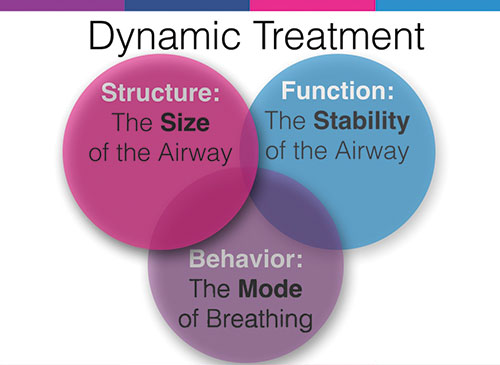

The good news is that dynamic treatment approaches are available that address the three major aspects of physiology: Structure, Function and Behavior. Helping the face, jaws, and airway grow optimally helps reduce flow limitation and gives teeth plenty of room to erupt. Optimizing the functions of sleep, nutrition and posture lessens the swelling, inflammation, and obstruction of the airway. And training proper breathing mechanics, tongue posture, and swallowing mechanics eliminate the soft tissue dysfunctions.

Above all, educating and training four basic competencies of airway physiology can make a difference for people of all ages. Nasal, diaphragmatic breathing, lip competence, tongue-to-palate resting posture, and swallowing without using facial muscles can help an adult sleep better and can help a child grow up with straight teeth.

You CAN optimize the outcome of growth and development for your patients and help overcome the symptoms by curing what ails modern man.