CE Expiration Date: August 30, 2022

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 370

Dental Sleep Practice subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking this quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article.

- Discuss with their team and peers the implications of the policy statement for their practice

- Lead their teams to develop communication skills so the changes can be introduced to patient communications

- Have confidence their practice is working towards the highest ideals of collaborative medical/dental services.

Editor’s intro: In part I of this special feature, six articles explore the ADA policy and what leaders say about sleep-related breathing disorders’ impact on a dental practice.

Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders: The Role of the Dentist

by Jeffrey Cole, DDS

President, American Dental Association

An ADA Perspective

In 2017, the American Dental Association (ADA) took a major step toward helping patients who suffer from sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBDs). That year, the ADA House of Delegates adopted a policy urging dentists to play a role in the care of patients with certain SRBDs.

The ADA believes that dentists are uniquely positioned to collaborate with physicians in the care of patients with SRBDs in part, because of their knowledge and expertise in the oral cavity and in oral appliance therapy. Evidence shows that custom-made, titratable oral appliances (OA) can help alleviate the effects of SRBD in adults. While OAs have been generally considered inferior to positive air pressure devices such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), their superior acceptance by patients has shown them to often provide equivalent medical benefit.

Developing the ADA Policy

The ADA started researching the issue in 2015. ADA’s House of Delegates directed that a policy on the dentist’s role in SRBD be developed by the appropriate ADA agencies. Together, the Councils on Scientific Affairs (CSA) and Dental Practice began investigating the scientific literature for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and selected randomized trials for the use of oral appliances in the management of sleep-related breathing disorders, primarily obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In addition, they reviewed and graded clinical practice guidelines from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine on the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliances1 as well as a consensus guideline co-authored and published in 2015 from dental sleep medicine societies in Italy.2

The goal was to develop an overview of the “state of the science” behind the use of oral appliances in the management of SRBDs. This document was reviewed by a CSA-assembled workgroup of subject-matter experts, as well as members of the ADA Council on Dental Practice. This phase of the process resulted in an evidence brief, Oral Appliances for Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders.

The first policy draft was posted on ADA.org for external comments and feedback and the response was astounding. More than 87 comments poured in from a wide range of readers, including members of the public, dentists, physicians and other healthcare providers, researchers and professional organizations, including some from outside the United States. To ensure that all the feedback was considered, comments were categorized according by clinical topics, including early intervention/growth and pediatrics, orthodontics, diagnostic, surgical treatment and portable home monitoring, and non-clinical topics including policy language, general comments, and supportive comments.

The Council on Dental Practice then reviewed those comments and determined appropriate changes. A second draft was posted for another round of comments. After considering the 47 additional comments and again amending the policy statement, the Council submitted the policy for consideration by the 2017 ADA House of Delegates in Atlanta, where it was adopted.

What Does the Policy Say?

The policy states that dentists can and should play an essential role in the multidisciplinary care of patients with certain sleep related breathing disorders and are well positioned to identify patients at increased risk of SRBD. SRBDs can be caused by several multifactorial medical issues and are, therefore, best treated through a team approach with collaboration between the patient’s dentist and physician. Properly trained dentists are uniquely positioned with the knowledge and expertise necessary to provide such therapy.

In children, the dentist’s recognition of suboptimal early craniofacial growth and development or other risk factors may lead to medical referral or orthodontic/orthopedic intervention to treat and/or prevent SRBD. Oral appliance therapy is a dentist-provided choice to treat SRBD; surgical modalities and positive airway pressure devices are employed by physicians. Various surgical modalities exist to treat SRBD when CPAP or OA therapy is inadequate or not tolerated.

What Role Should Dentists Play?

The policy encourages dentists to play a role in patient screening, and when necessary, to consult with the patient’s physician. Dentists should assess patients for suitability of OA upon the referral of a physician, and if appropriate, fabricate and titrate the oral appliances and/or refer the patient to other health care professionals as needed for further treatment.

Where Do We Go from Here?

The extent to which dentists can implement this policy is determined by state dental boards. The ADA encourages dentists to investigate the scope of practice in this area in their state, educate themselves about SRBDs and, where appropriate, begin to provide care to their patients for SRBDs through screening, professional collaboration and treatment.

The ADA has resources available to help you and your patients learn more about SRBDs. Several CE courses are available on ADA.org, and the topic will be featured in a two-day workshop at the 2019 ADA/FDI World Dental Congress in San Francisco. To help educate your patients, the ADA has developed a brochure on sleep apnea and provides more information on MouthHealthy.org.

The ADA is committed to promote dentistry’s involvement in helping achieve optimal health for all.

References:

- Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11(7):773-827.

- Levrini L, Sacchi F, Milano F, et al. Italian recommendations on dental support in the treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2015;6(3-4):81-6.

Author:

Jeffrey M. Cole, DDS, MBA, a general dentist from Wilmington, Delaware, is president of the American Dental Association. Dr. Cole served as the ADA Fourth District Trustee. He served as the chair of both the Budget and Finance Committee and the Strategic Planning Committee. Dr. Cole was a member of the ADA Council on Dental Practice before being elected a trustee. Dr. Cole is involved in several additional dental organizations including the Academy of General Dentistry, where he served as president in 2012–13. He is a Fellow of the International College of Dentists, the American College of Dentists and the Academy of Dentistry International. He was president of the Delaware State Dental Society in 2008–09 and received the Distinguished Service Award from that society in 2015. Dr. Cole received a bachelor’s degree from Villanova University in Villanova, Pennsylvania. He received his doctoral degree from Georgetown University School of Dentistry in Washington, D.C. He later earned a master’s in business administration degree from The Fox School of Business at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Jeffrey M. Cole, DDS, MBA, a general dentist from Wilmington, Delaware, is president of the American Dental Association. Dr. Cole served as the ADA Fourth District Trustee. He served as the chair of both the Budget and Finance Committee and the Strategic Planning Committee. Dr. Cole was a member of the ADA Council on Dental Practice before being elected a trustee. Dr. Cole is involved in several additional dental organizations including the Academy of General Dentistry, where he served as president in 2012–13. He is a Fellow of the International College of Dentists, the American College of Dentists and the Academy of Dentistry International. He was president of the Delaware State Dental Society in 2008–09 and received the Distinguished Service Award from that society in 2015. Dr. Cole received a bachelor’s degree from Villanova University in Villanova, Pennsylvania. He received his doctoral degree from Georgetown University School of Dentistry in Washington, D.C. He later earned a master’s in business administration degree from The Fox School of Business at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Screening Patients to Find Who is at Risk of SRBD

by Steven Lamberg, DDS

The ADA’s position paper on “The Role of Dentistry in the Treatment of Sleep Related Breathing Disorders” establishes that dentists play an “essential role” in identifying and caring for these patients. The document states dentists “should be encouraged” to screen for these disorders as part of a medical and dental history. This call to action is not exactly a mandate. Rather than arguing about the absolute level of responsibility dentists have to screen patients, I will lay out what screening is and let the tides of time calibrate the level of our actual responsibilities.

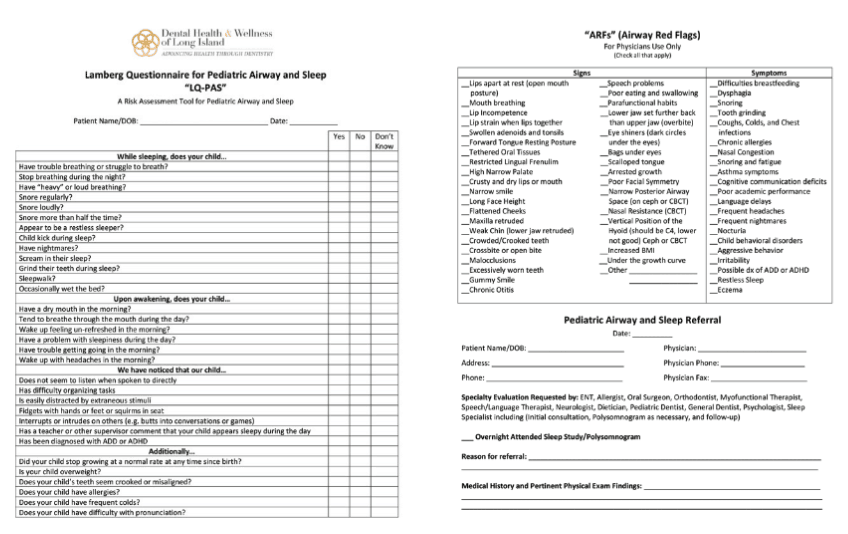

Download the questionnaire by clicking here.

Screening is more than handing the patient a questionnaire and reviewing their responses, but it is also not a definitive test for a disease. Screening is intended to identify risk, to indicate who should be sent for ‘the next test.’ Questionnaires such as the STOP-BANG and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale have been “validated”, which means that they have been shown to be statistically meaningful in assessing risk of having SRBDs.

Although valuable, a screening questionnaire needs to be combined with a thorough clinical examination to best illuminate the complete health status of the patient. It is important to assert that questionnaires can do much more than assess risk. They can serve to educate patients about the correlation between many medical conditions and airway problems. This knowledge gives patients the opportunity to “treat the cause” rather than the symptom. We also have the opportunity to become airway advocates through political action, to influence public school systems to mandate the use of questionnaires to test for airway problems along with currently mandated evaluations for hearing and vision deficiencies.

Download the form by clicking here.

The first step is making these questionnaires available to all new patients as well as making it part of your health history update at hygiene visits. Although the amount of health information that can potentially be unlocked by reviewing a patient’s answers is invaluable, not everyone shares this view. In fact, the question of “who do you give the questionnaire to” has been probed by many. Should every patient be asked to complete one? In 2017, the United States Preventative Services Task Force “USPSTF” concluded that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in asymptomatic adults.1 The problem with their conclusion is that we don’t have a clear definition of “symptomatic” because of a general lack of appreciation of the correlation between medical conditions and airway problems. As the patient’s basic health history will lay out medical conditions that confer an increased risk of having SRBDs, it becomes incumbent upon us to know the increased odds ratios of having SRBDs associated with all medical conditions. We need to think about the correlation between airway/sleep issues and problems with all of the body’s systems. Oxidative stress and sympathetic activation associated with problematic breathing create an inflammatory load that impacts all of the systems in our bodies. Adding the patient’s medical condition status to the typical clinical signs and symptoms being evaluated will bring us a step closer to discovering all the patients who require further objective testing to confirm the need for treatment. The Lamberg Questionnaire (LQ) is built on revealing the correlation between airway and overall level of health. I composed the LQ by mining increased odds ratios of having SRBDs from over 300 articles, and it has been refined by experts in the different fields and updated continually. I have no financial interest in the LQ or the LQ-Pediatric Airway and Sleep (LQ-PAS) and believe that every practice will benefit from making it part of their new patient protocol. (Free download available at www.LambergSeminars.com)

Every person will benefit from a more comprehensive approach in your practice that includes understanding risk factors, identifying clinical manifestations, using screening questionnaires, and employing other observations that indicate the need for further testing.

Children should be viewed in a more urgent manner due to the impact SRBDs can have on growth and development. Risk factors for children include: a family history of SRBDs, various syndromes, behavioral problems, and craniofacial abnormalities such as high narrow hard palate, overlapping incisors, and crossbites. Signs and symptoms can be checked off on a simple questionnaire like the LQ-PAS. See table 1 LQ-PAS (Note that this 2 page questionnaire needs to be evaluated along with the medical history and a thorough clinical exam.)

Adults have less concern for ongoing growth and development problems but a careful evaluation of medical history and a clinical examination are crucial. All of the body’s systems must be reviewed to see if there are conditions associated with an increased risk of SRBDs. See table 3. (This questionnaire should be evaluated along with the medical history as well as a thorough clinical exam)

With a better understanding of which conditions are correlated with SRBDs, screening the higher risk patients will be accomplished much more efficiently.

Although it is worth mentioning that the relationship between SRBDs and combinations of blood biomarkers show promise in providing us with a higher level of screening accuracy in the future, at this time we must rely on our clinical examinations and questionnaires to best find the individuals whose health is at risk and recommend more detailed testing for accurate diagnosis.

References:

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017;317(4):407–414. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20325.

Author:

Steven Lamberg, DDS, practices all phases of dentistry in Northport, New York. He is a graduate of the Kois Center and serves as a scientific advisor for airway there. He writes and lectures nationally on topics related to airway health.

Steven Lamberg, DDS, practices all phases of dentistry in Northport, New York. He is a graduate of the Kois Center and serves as a scientific advisor for airway there. He writes and lectures nationally on topics related to airway health.

Organized Dentistry Takes on Children’s Airway

by Barry D. Raphael, DMD, MS, and Mark A. Cruz, DDS

The 2017 ADA Policy Statement includes a broad statement regarding the treatment of children with sleep or breathing disorders: “In children, screening through history and clinical examination may identify signs and symptoms of deficient growth and development, or other risk factors that may lead to airway issues. If risk for SRBD is determined, intervention through medical/dental referral or evidenced based treatment may be appropriate to help treat the SRBD and/or develop an optimal physiologic airway and breathing pattern.”

The last portion of the statement charges us with a more comprehensive approach to dealing with children.

There is wisdom in the phrase “optimal physiologic airway and breathing pattern” that goes well beyond having dentists play a supportive role to physicians. Dentists and orthodontists are far better prepared to influence the growth and development of a child’s airway than are physicians.1-6 We can influence optimal wellness to lower risk factors for SRBD. Therefore, it is critical for every dentist to understand the underpinnings of this part of the policy.

Essentially, having an optimal physiologic airway and breathing pattern means that the upper airway – from the tip of the nose to the larynx – is easy to breathe through AND that the child knows how to breathe through it easily.

The basic premise of having an airway that’s “easy to breathe through” is that air should be able to pass unimpeded in any way. Air swirls inside the nose to clean and humidify the air, but once it reaches the softer parts of the airway, we want “laminar flow,” with no turbulence or swirling as the air passes through.7-9 Turbulence creates negative pressure that pulls on the flexible walls of the airway, making it narrower and impeding flow. This is the origin of snoring, Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Since breathing is such a critical part of our physiology, our bodies will successfully compensate for anything that impedes it. Like an overresponsive immune system, the struggle to breathe easily has negative consequences, leading to a downward spiral of poor facial growth, poor oral function, poor sleep, and overall poor health.11

Getting a child out of that negative spiral is the essence of the ADA’s policy.

The Consequences of Poor Breathing in Children

It is important to know that a child can have flow limitation and fragmented sleep and NOT have sleep apnea or desaturations. Daytime problems, like mouth breathing, nasal congestion, and over breathing can be the risk factors that lead to nighttime flow limitation.

In other words, the problem is breathing, not just sleep. Children with poor breathing patterns can have problems with brain and neurocognitive development, fragmented sleep, behaviors of hyperactivity or sleepiness, chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system, disregulation of digestive and metabolic hormones, and more.11-13

Clinical Implications: Screening and Outcomes

Our first obligation is to screen every patient for risk factors of turbulent air flow.

The ADA has sanctioned development of a screening tool that can be easily implemented in the dental practice, using a questionnaire and clinical data.

Simple questions about snoring, restless sleep, bruxism, open mouth posture, and behavioral issues are included in the initial and periodic exams.

The clinical exam will look for some of the phenotypic risk factors such as a narrow dental arch, malocclusion, a tethered tongue, a long soft palate, and vertical development of the lower third of the face.

Together, they will direct the clinican to either refer the patient directly to a sleep physician or do a more thorough second level screening, which will also be defined in the ADA’s recommendations.

A second task force is looking to define the favorable outcomes that will be the goal of effective treatment and the metrics used to measure them.

Examples of favorable outcomes are: 1) Nasal breathing as the dominant mode, 2) Good lip competence (instead of mouth breathing), 3) The tongue positioned on the palate to support good bony growth, 4) A competent swallow using only lingual, not facial, muscles, 5) Good body posture, 6) A peaceful, rejuvenating night’s sleep, 7) Efficient intake and delivery of oxygen to all body tissues, and 8) Improved health and wellbeing. Many of these outcomes have direct or surrogate metrics that can be used to characterize them.

Clinical Implications: Interventions

Procedures that help develop an optimal physiologic airway will focus on maximizing tongue space in the anterior of the face using the natural growth of the jaws, guided, if necessary, by appropriate professional intervention.

Optimizing a breathing pattern requires both physical therapies and behavioral modification. First, a clean and clear nose is fundamental. Then, any physical restrictions to good posture or movement of the diaphragm have to be addressed. This may require an interdisciplinary team working with the dentist.

Because habitual compensations are responsible for much of the damage we see to the facial skeleton and airway, it is crucial that these habits be re-trained as soon as they are discovered. No longer is the age for treatment defined by dental staging. Success is not limited to straight teeth.

This is a very exciting time to be in dentistry. The ability to help a child breathe better, sleep better and perform better will give them an head start to a life of good health. Join us as we take dentistry and our children into the bright 21st Century. And join us for the Third ADA Conference on Children’s Airway Health in June 2020.

References:

- Eichenberger M, Baumgartner S. The impact of rapid palatal expansion on children’s general health: a literature review. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2014;15(1):67-71.

- Mew JR, Meredith GW. Middle ear effusion: an orthodontic perspective. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(1):7-13.

- Iwasaki T, Saitoh I, Takemoto Y, et al. Tongue posture improvement and pharyngeal airway enlargement as secondary effects of rapid maxillary expansion: a cone-beam computed tomography study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143(2):235-245.

- Sayinsu K, Isik F, Arun T. Sagittal airway dimensions following maxillary protraction: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod. 2006;28(2):184-189.

- Villa MP, Rizzoli A, Miano S, Malagola C. Efficacy of rapid maxillary expansion in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: 36 months of follow-up. Sleep Breath. 2011;15(2):179-84.

- Katyal V, Pamula Y, Martin AJ, et al. Craniofacial and upper airway morphology in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143(1):20-30.

- Catalano P, Walker J. Understanding nasal breathing: the key to evaluating and treating sleep disordered breathing in adults and children. Curr Trends Otolaryngol Rhinol. 2018;CTOR-121.

- Rappai M, Collop N, Kemp S, deShazo R. The nose and sleep-disordered breathing: what we know and what we do not know. Chest. 2003;124(6):2309-2323.

- Guilleminault C, Sullivan SS. Towards Restoration of Continuous Nasal Breathing as the Ultimate Treatment Goal in Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Enliven: Pediatr Neonatol Biol. 2014;1(1):001.

- Molfese DL, Ivanenko A, Key AF, et al. A one-hour sleep restriction impacts brain processing in young children across tasks: evidence from event-related potentials. Dev Neuropsychol. 2013;38(5):317-336.

- Horne RSC, Roy B, Walter LM, et al. Regional Brain Tissue Changes and Associations with Disease Severity in Children with Sleep Disordered Breathing. SleepJ. 2018;1-10.

- Bonuck K, Rao T, Xu L. Pediatric sleep disorders and special educational need at 8 years: a population-based cohort study. Pediatrics. 2012;130(4):634-642.

- Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Neurocognitive and behavioral morbidity in children with sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13(6):505-509.

Author:

Barry D. Raphael, DMD, received dental degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine and his Certificate in Orthodontics from the Fairleigh-Dickinson University School of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics. He is a lecturer and staff member at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, Pediatric Dental Residency; Clinical Instructor at Institute for Family Health. He is a life member of the American Dental Association, a member of the American Association of Orthodontists, and Fellow of the American College of Dentists. Dr. Raphael is in private practice of orthodontics at The Raphael Center for Integrative Orthodontics Clifton, New Jersey and is owner/director of The Raphael Center for Integrative Education.

Barry D. Raphael, DMD, received dental degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine and his Certificate in Orthodontics from the Fairleigh-Dickinson University School of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics. He is a lecturer and staff member at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, Pediatric Dental Residency; Clinical Instructor at Institute for Family Health. He is a life member of the American Dental Association, a member of the American Association of Orthodontists, and Fellow of the American College of Dentists. Dr. Raphael is in private practice of orthodontics at The Raphael Center for Integrative Orthodontics Clifton, New Jersey and is owner/director of The Raphael Center for Integrative Education.

Mark A Cruz, DDS, graduated from the UCLA School of Dentistry in 1986 and started a dental practice in Monarch Beach, California upon graduation. He has lectured nationally and internationally and is a member of various dental organizations including the American Academy of Gnathologic Orthopedics (AAGO), North American Association of Facial Orthotropics (NAAFO), Pacific Coast Society for Prosthodontics, and the American Academy of Restorative Dentistry. He was a part-time lecturer at UCLA and member of the faculty group practice and was past assistant director of the UCLA Center for Esthetic Dentistry. He has served on the National institute of Health/National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) Grant Review Committee in Washington D.C., and on the Data Safety Management Board (DSMB) for the National Practice-Based Research Network (NPBRN) overseen by the NIDCR, as well as on the editorial board for the Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice (Elsevier).

Mark A Cruz, DDS, graduated from the UCLA School of Dentistry in 1986 and started a dental practice in Monarch Beach, California upon graduation. He has lectured nationally and internationally and is a member of various dental organizations including the American Academy of Gnathologic Orthopedics (AAGO), North American Association of Facial Orthotropics (NAAFO), Pacific Coast Society for Prosthodontics, and the American Academy of Restorative Dentistry. He was a part-time lecturer at UCLA and member of the faculty group practice and was past assistant director of the UCLA Center for Esthetic Dentistry. He has served on the National institute of Health/National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) Grant Review Committee in Washington D.C., and on the Data Safety Management Board (DSMB) for the National Practice-Based Research Network (NPBRN) overseen by the NIDCR, as well as on the editorial board for the Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice (Elsevier).

A New Hope

by Todd Morgan, DMD

Nope, this not about Star Wars or a galaxy far, far away, but it is about the now, and organized dentistry coming to terms with policy regarding the dentist’s role in treating airway disorders during sleep, for adults and children. This is our ADA responding to the great scourge of OSA, and it is truly, A New Hope.

The essence of the ADA policy statement issued in 2017 reflects the important role of the dentist in detecting potential sleep apnea among our patients. I consider us as “first responders” to many of our patients’ medical needs, including screening for high blood pressure, auto-immune disorders, and now OSA. The old adage that says: “the oral cavity is the window to overall health” holds true. Most of the signs of sleep apnea are easy to see in the mouth, and with the help of quick questionnaire(s), screening for potential OSA is easy AND appropriate.

Many of us in leadership have lobbied to for a long time to simplify the screening for OSA and have the ADA come forward with a policy statement on the responsibilities of dentists to screen for this deadly epidemic. Now that we have this bold move in place, I am pleased that a new task force is working on the prevention of OSA by forming reasonable protocols for screening by pediatric dentists. A growing number of our orthodontic colleagues are well-steeped in airway awareness – be sure to ask those in your community about it.

Promoting the proper growth and development of the airway as well as protecting and healing those adults with Obstructive Sleep Apnea are some of the best things that have happened to dentistry in a long time. We dentists have an incredible set of tools to improve the lives of our patients – both young and old – like never before. We will need to learn to operate with a team approach and with our medical colleagues to make this happen. A new twist for many of us! Very exciting, but there are some rules. We stand with a policy in hand that may quickly fall out of date as studies continue. I cannot imagine a wider frontier ahead!

Good scientific evidence has proven the veracity of oral appliance therapy for mild and moderate OSA. We are on very solid ground here, bolstered by the publication of standards of care by the AADSM and the AASM, such as: Dental Sleep Medicine Standards for Screening, Treating and Managing Adults with Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders and Clinical Practice Guideline for Oral Appliance Therapy. So our stage is set for mild and moderate, but OAT is also viewed as a viable alternative for severe OSA when CPAP fails. All of you that have done this work for a while know that we hit home runs often for patients with every level of diagnosis, but we also have our failures; this is exactly why we should always work as a team with our physician colleagues.

Research is the key to successfully relating to our physicians, who have been trained to rely on validated evidence to make all of their decisions about patient care. I remember the first meta-analysis paper I read on oral appliance therapy was published in the Journal Chest (Pancer, Hoffstein, December 1999). They concluded from an analysis of roughly 3000 patients in past studies that “adjustable mandibular positioning appliance is an effective treatment alternative for some patients with snoring and sleep apnea.” Since then we have proved in many more studies that these results are repeatable and reliable. A very recent meta-analysis publication: “Cardiovascular effects of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis’” (A. Hoekema, et al.) continues to show the benefits of the work we do in DSM. We are armed with the evidence we need to continue our conversations with MDs. Now we must begin to challenge the status-quo that calls for CPAP at every turn and bring oral appliances to the forefront of treatment for OSA. Good communication with colleagues is at the cornerstone of any successful Dental Sleep Medicine practice.

Dentistry is poised to become the front line of uncovering sleep apnea. OSA patients are everywhere and they need the medical referral we can provide. But dentistry may not have the full confidence we deserve from our MDs – largely because we created that! For example, most physicians I know cringe at the term “TMJ” and retract in fear. Fortunately, dentistry as a profession has become less isolationistic over time, promoting a new expectation of evidence-based data and proof of “best practice” in fields like periodontics, implantology, oral surgery, and now DSM. Notably, DSM has become a unique exercise in promoting collegiate interaction between dentists and physicians. I actually think this is the coolest part of DSM, where we can explore this field together with our knowledgeable friends and share in the glory of our achievements!

This is a time to move toward our medical colleagues instead of away from them. This is the time to create mutually beneficial relationships that promote the best care our patients can receive. Embrace the New Hope and start a conversation with your MDs on the established validity of OAT and show them the evidence. Our treatment is not inferior to CPAP, and I say it is irresponsible to not fully embrace our duty together, as healers.

Author:

Dr. Todd Morgan is a graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, and became a Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine in 1999. He is recognized as an expert in the field of Dental Sleep Medicine and lectures nationally and internationally on oral appliance therapy. His team has completed several NIH funded clinical trials, and he has authored several peer-reviewed articles and books on the treatment of sleep apnea and snoring with dental appliances. He has served 8 years in leadership and educational roles with the AADSM. His current areas of interest include pharyngeal exercise for OSA, and the development of phenotyping models for successful Oral Appliance Therapy. He has extensive clinical experience in DSM and is now exploring airway CBCT analysis. Most recently, Dr. Morgan’s team are the recipients of three research awards from the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine in 2019.

Dr. Todd Morgan is a graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, and became a Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine in 1999. He is recognized as an expert in the field of Dental Sleep Medicine and lectures nationally and internationally on oral appliance therapy. His team has completed several NIH funded clinical trials, and he has authored several peer-reviewed articles and books on the treatment of sleep apnea and snoring with dental appliances. He has served 8 years in leadership and educational roles with the AADSM. His current areas of interest include pharyngeal exercise for OSA, and the development of phenotyping models for successful Oral Appliance Therapy. He has extensive clinical experience in DSM and is now exploring airway CBCT analysis. Most recently, Dr. Morgan’s team are the recipients of three research awards from the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine in 2019.

Evaluating Patients for Success – It’s More Than What You Can See

by Gy Yatros, DMD

Evaluating patients for Dental Sleep Therapy (DST) is an essential part of successful treatment in Dental Sleep Medicine (DSM). Treating patients with DST requires our collaboration with the medical community. Although this may seem like an obstacle to dentists new to DST it is an incredible opportunity to broaden our reach as healthcare providers in our community. Through our interactions, physicians can help us better understand our patients’ medical condition as we have an opportunity to enlighten them on our medical dental concerns such as systemic oral health issues in addition to OSA. Our collaboration requires that our patients have a medical diagnosis from a sleep physician, copies of their clinical notes, a prescription for DST and a Letter of Medical Necessity (LOMN). In addition, we should regularly communicate with our DSM team on our patients’ progress. Not until our patients have a medical diagnosis and we have fully communicated with our patients’ other health care providers should we begin to treat our OSA patients in the dental office.

Once our patients have a diagnosis of OSA, we can begin our evaluation for DST. Candidacy evaluation is a multifactor process that requires a step-wise approach by a trained DSM dentist. At a high level the goals of the DSM evaluation are to determine if the patient’s craniofacial anatomy and treatment goals are conducive to a positive treatment outcome. That may sound straightforward but in reality, it often isn’t. Complex dental histories, TMJ issues, missing dentition, nasal airway problems and patient compliance can complicate the former while unstandardized, debated and ill-defined treatment goals can muddy the latter. A successful DSM exam begins with the realization that we are heading into grey areas of medicine which often conflict with the dentist’s analytical and precise nature. But don’t give up hope – with education and experience, dentists can help patients navigate this complex process to achieve life altering and lifesaving outcomes.

Let’s begin in the dentist’s comfort zone with a physical evaluation for DST candidacy. Our evaluation should include a review of the patient’s dental history, an oral facial evaluation, and a review of short-term future dental needs. Simply stated, if the patient is to utilize DST, will the teeth, TMJ and other craniofacial anatomy be able to tolerate the forces generated by the device while producing minimal unwanted side effects?

Careful examination of the dentition is required. Are there missing teeth, periodontal issues, or teeth with minimal undercuts which could result in retention challenges? Are there any immediate dental needs? This is where the dentist must put on their DSM hat which may often conflict with our focus on optimal oral health. We will routinely need to make challenging decisions while weighing restorative needs against the possibility of postponing DST. The importance of the dental needs must be weighed against the patient’s OSA severity, co-morbidities, age and other available and attempted treatment alternatives. Our job is to help guide our patients in making the best treatment choice based on these many variables.

Our DSM evaluation should also include evaluation of the oral cavity, nasal airway, TMJ and the muscles of the head and neck. While evaluating the oral cavity, we look at things like tongue size and position, arch form, and tonsillar and Mallampati classifications. We must carefully document our findings as to how these items affect the airway and we will ultimately use all collected data to steer device selection for the patient.

One mantra you will often hear in DSM is “Don’t forget the nasal airway!”. Nose breathing is extremely important for DSM success as well as the patient’s overall health. There are chapters and books dedicated to this one subject but suffice it to say that patients who breathe through their noses while sleeping will have improved success with DST.

A careful TMJ and muscular exam is a mandatory part of our examination. We must look for internal joint derangements, muscle tenderness and evaluate the patient’s range of motion. Instruments like the George Gauge or Pro Gauge can help measure the patient’s ability to protrude the mandible. Maximum incisal opening, sore muscles, TMJ issues and history of bruxism will come into play during our evaluation and device selection process.

Lastly, our craniofacial examination should at a minimum include radiographs of the dentition to help us determine the stability of the teeth. We should look for short roots, periodontal bone loss, abscesses and other conditions that could affect our treatment outcomes. We recommend a CBCT for our patients, which also allows evaluation of the sinuses, TMJ’s, nasal and oral airways. Unless you are an expert in radiology, it is advisable to have a radiologist interpret these large fields of view to ensure proper evaluation and documentation.

This may sound like a lot of information, but when proper systems are utilized, the DST evaluation can be completed in a minimal amount of time. Ultimately, the evaluation will determine if the anatomy is stable enough for DST, which device is best suited for the individual patient, and the three-dimensional position where the device will be constructed.

The ADA guidelines call on us to determine if fabricating an oral appliance is ‘appropriate.’ Patient autonomy and proper medical practice means that we must take into account their preference, history, and our judgement of likelihood this therapy will be successful. The dentist and patient should discuss the likelihood of achieving the agreed upon goals, the risks associated with DST, and other treatment options. By discussing the information in a knowledgeable, caring, and sincere manner, most qualified patients will readily choose DST to treat their airway problems. In 30 years of practicing dentistry, nothing even comes close to the satisfaction I have experienced in providing this valuable service. With experience and conviction, the dental team will soon realize the benefits of bringing Dental Sleep Medicine into their practices while helping their patients live better and live longer.

Author:

Dr. Gy Yatros has practiced dental sleep medicine for over fifteen years and is a key opinion leading international lecturer in the area of sleep-disordered breathing and dental sleep medicine. He has offices in Bradenton, Sarasota, and Tampa, Florida devoted exclusively to the treatment of sleep disordered breathing. He is Co-Founder and CEO of Dental Sleep Solutions and the DS3 System for Dental Sleep Medicine Implementation. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine (ABDSM) and is an Affiliate Assistant Professor of the Department of Internal Medicine with the University of South Florida, College of Medicine.

Dr. Gy Yatros has practiced dental sleep medicine for over fifteen years and is a key opinion leading international lecturer in the area of sleep-disordered breathing and dental sleep medicine. He has offices in Bradenton, Sarasota, and Tampa, Florida devoted exclusively to the treatment of sleep disordered breathing. He is Co-Founder and CEO of Dental Sleep Solutions and the DS3 System for Dental Sleep Medicine Implementation. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine (ABDSM) and is an Affiliate Assistant Professor of the Department of Internal Medicine with the University of South Florida, College of Medicine.

Informed Consent in Dental Sleep Medicine

by Ken Berley, DDS, JD, DABDSM

”Dentists should obtain appropriate patient consent for treatment that reviews the proposed treatment plan, all available options and any potential side effects of using OAT and expected appliance longevity.1”

Consent is an act of reason, accompanied with deliberation, the mind weighing as in a balance the good or evil on each side. It means voluntary agreement by a person in the possession and exercise of sufficient mental capacity to make an intelligent choice to do something proposed by another.2

Every patient possesses the legal right to determine the treatments and procedures which will be employed to control any disease or condition that he or she may have. Medical informed consent is the legal embodiment of the concept that all patients of sound mind and legal capacity have the right to make decisions affecting their health. It is generally accepted that patients should be informed of the potential risks and benefits flowing from their medical decisions.3

Dentists must become familiar with any state statutes which regulate the informed consent process for your particular state or jurisdiction.

Medical informed consent is ethically, morally, and legally mandated by the fiduciary duty flowing from the doctor-patient relationship. Ethically, dentists are legally bound and morally obligated to identify the best treatments for each patient on the basis of available medical evidence. A discussion must then occur where the patient is informed of the hoped-for benefits and the potential risks associated with the proposed treatment. Dentist are required to disclose the risks associated with the proposed procedure and the risks of the alternatives to enable patients to make knowledgeable decisions.4 A patient’s understanding of the potential risks of a proposed treatment is critical to medical informed consent.

Elements of Valid Informed Consent

For consent to be valid, it must be voluntary and informed, additionally, the person consenting must have the capacity to make the decision.

Disclosure

Informed consent must be preceded by disclosure of sufficient information; however, the specific information varies based on the patient and procedure. Accurate and relevant information must be provided in a form (using non-scientific terms) and language that the patient can understand. Informed consent is NOT a patient’s signature on a dotted line obtained routinely by a staff member. Patients should be given the opportunity to ask questions.

The information disclosed should include:5

- The condition/disorder/disease that the patient is having/suffering from

- Necessity for further testing

- Natural course of the condition and possible complications

- Consequences of non-treatment

- Treatment options available

- Potential risks and benefits of treatment options

- Duration and approximate cost of treatment

- Expected outcome

- Follow-up required

For DSM, consent must address dental complications associated with oral appliance therapy, as well as, systemic health consequences of non-treatment of SRBD.

Properly trained dentists understand the myriad of complications that can arise from OAT – the author specifically warns EVERY patient of all of the possible negative side effects, and that complications related to oral appliance use have been minor. Patients are warned that it is their responsibility to immediately inform our office of any issues and to adhere to recommended management appointments.

Other treatment choices for the patient’s specific conditions should be discussed and appropriate resources provided so they can seek the information they need to inform themselves.

Expected longevity of an oral appliance varies greatly depending on the appliance chosen and the clinical presentation of each patient. Therefore, it may be difficult to accurately predict. The author cautions against presenting information which might cause the patient to think that it is guaranteed to last a certain period of time.

With appropriate disclosure, patients may be treated under conditions which are less than ideal, such as risky periodontal support or a history of TMJ disorders. Practitioners should disclose the information necessary to achieve informed consent based on the particular patient’s clinical presentation.

It is possible that consent can result in a refusal to proceed with therapy. Documentation must show the information that was provided and that the patient refused treatment with full knowledge of the seriousness of the decision.

Legal Capacity

Patient has adequate capacity if he/she is able understand the information presented, make medical decisions, and communicate the decision to another party. Since severe sleep deprivation has been adjudicated to limit the capacity to provide informed consent, patients should be evaluated on their ability to actively participate in a conversation. When a dentist feels that a patient may be incapacitated, if no legal guardian has been appointed, a close family member should participate in all discussions and sign as a witness to the informed consent document.

Documentation

A well written informed consent document is mandatory to minimize legal risk and be able to present the evidence in court that a consent discussion occurred. A patient is always free to contest the validity of the informed consent, despite a signed consent form.6

Conclusion

Informed consent is a most important document in your medical record to prevent malpractice lawsuits. Most plaintiff’s attorneys are hesitant to pursue a cause of action when the injury that the patient is complaining of is clearly listed on a consent form.

Each practitioner should establish protocols that ensure proper consent is obtained from every patient. These simple steps can lead to better patient communications and less overall risk to you and your practice.

References:

- ADA Policy Statement: The Role of Dentistry in the Treatment of Sleep Related Breathing Disorders. Adopt ed 2017

- Blacks Law Dictionary 6th Edition West Publications

- Faden, Ruth R.; Beauchamp, Tom L.; King, Nancy M.P. (1986). A history and theory of informed consent. New York: Oxford University

- Merz JF, Fischhoff B. Informed consent does not mean rational consent: cognitive limitations on decision-making. J Leg Med. 1990;11(3):321-350.

- Etchells E, Sharpe G, Walsh P, Williams JR, Singer PA. Bioethics for clinicians: 1. Consent. CMAJ. 1996;155: 177–80.

- Parikh v Cunningham, 493 So 2d 999 11 FL L. Weekly 309 (Fla, 1986).

Author:

Dr. Ken Berley is a dentist/attorney with over 35 years of dental experience and over 22 years in the legal profession. For the past 10 years, he has focused his practice on the treatment of Sleep Disordered Breathing and TMD. As the only DDS/JD/Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine, he stays busy lecturing and consulting in the areas of risk management and the development of a successful dental sleep medicine (DSM) practice.

Dr. Ken Berley is a dentist/attorney with over 35 years of dental experience and over 22 years in the legal profession. For the past 10 years, he has focused his practice on the treatment of Sleep Disordered Breathing and TMD. As the only DDS/JD/Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine, he stays busy lecturing and consulting in the areas of risk management and the development of a successful dental sleep medicine (DSM) practice.

Dr. Berley has written numerous consent forms that are used in general and dental sleep medicine practices. He is the co-author of The Clinicians Handbook for Dental Sleep Medicine (Quintessence). With his unique background he provides consulting services for various insurance companies and actively defends and advises dentists who are facing legal challenges. Dr. Berley is the President of Dental Sleep Apnea Team, a consulting firm offering in-office training on Dental Sleep Medicine, consent forms and other documents to assist the DSM practice.

Glennine Varga, a dental sleep medicine coach, also discusses the ADA policy and its ramifications. Read her article, “ADA, Airway and the Team”.