CE Expiration Date: August 30, 2024

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 730

Educational Aims

This self-instructional course aims to discuss a “Physician-Dentist Collaboration” concept for the management of Sleep Disordered Breathing, providing both literature evidence and details on an existing working model of this approach.

Expected Outcomes

Dental Sleep Practice subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading the article. Correctly answering the questions will exhibit the reader will:

- Learn about how uniquely positioned dentistry is to help manage Sleep Disordered Breathing

- Identify how OAT compares to PAP therapy

- Realize the current short comings in Sleep Medicine Research

- Understand current events as opportunities for OAT

- View patient care with OAT from an Physician-Dentist Collaborative viewpoint

Drs. John Viviano and Jon Bouzis discuss the significance of physician-dentist collaboration for management of sleep disordered breathing in this issue’s CE.

by John Viviano, DDS, D.ABDSM, and John Bouzis, DDS

Broken. This one word describes the current model for identifying, diagnosing, and treating sleep disordered breathing patients. Recognizing the need for change, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) sponsored the “Sleep Medicine Disruptors 2021” contest to stimulate creative thinking and to encourage constructive dialogue. Despite the American Dental Association’s (ADA) guidance on dental management of SDB,1 few dentists have followed the guidance, and those that have, struggle mightily due to a strong bias for use of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP). Unfortunately, CPAP therapy is hindered by poor patient adherence,2 leaving many patients either sub-optimally or totally unmanaged. This article reviews recent events that have the potential to significantly alter the face of sleep medicine and discusses the Physician-Dentist Collaboration model.

The Status Quo

More than 85% of the adult SDB population remain undiagnosed and children are mostly ignored.3 In diagnosed adults, approximately 85% are prescribed Positive Airway Pressure (PAP),4 for which adherence is 50% at 6 months5 and 17% at 5 years.6 Most non-adherent PAP patients simply remain unmanaged because the patient was advised that CPAP is “Gold Standard” and the only effective therapy.

Globally, the number of people affected by sleep apnea approaches 1 billion,3 contributing to the economic burden associated with unhealthy sleep, with health costs alone, approaching $700 billion per annum.7 In the United States, a 2015 report commissioned by the AASM found that sleep disorders are responsible for approximately $150 billion in workplace and motor vehicle accidents, lost productivity, and comorbid diseases.8 The American Board of Sleep Medicine (ABSM) website documents that there are approximately 7,500 board-certified sleep specialists serving a population of approximately 325 million people in the United States.9 Further exacerbating this obvious problem is the uneven geographic distribution of sleep specialists creating an accessibility imbalance throughout the United States.

What Is the AASM Looking for?

In an AASM podcast entitled Sleep Innovation (Podcast S3E9), the chairperson of the AASM Sleep Disruptors contest, Dr. Azizi Seixas, was interviewed by Dr. Seema Koshla, who stated the following, “I feel like we are all over-worked and that we are perpetually in survival mode”.

Dr. Seixas responded with, “We’ve got to re-imagine health care in terms of education, in terms of clinical care, in terms of research, in terms of venture…”, and “In order for us to do this we need an entire army.” He continued, “There aren’t enough sleep clinics out there to serve the great need we have in the community… we need to turn everything on its head and say how do we reach these individuals” and finally, “Develop new solutions of care and workflow so that we can better reach our people and that is the key!”

A recent article penned by the Board of Directors of the AASM discussing the future of Sleep Medicine stated, “…the future of sleep medicine lies in its ability to provide the workforce to care for sleep disorders across the population, from the cradle to the grave.”10 The article considered leveraging technology such as telemedicine and smartphone apps to improve efficiency, increase patient satisfaction, and reduce cost of care. These technological advances have already surfaced, and as you read on, you will also see how the confluence of current events may accelerate the acceptance of oral appliance therapy (OAT).

AHRQ Draft Report; A Gold Standard Tarnished

Recently, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a draft report that was commissioned by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to answer the following two questions:11

- What is the efficacy and comparative effectiveness of CPAP to improve clinical outcomes?

- What’s the evidence that apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is a valid surrogate of clinically significant outcomes?

The report found a low strength of evidence that hypertension, cardiovascular disease, heart attacks, stroke, diabetes, depression, and quality of life indices were improved with CPAP use. It is important to note that there is no literature demonstrating that OAT has a different impact on long-term healthcare outcomes.

The AASM Responds

In conjunction with over a dozen other organizations, the AASM penned a detailed response12 to the AHRQ providing several insights and suggestions which will hopefully be incorporated into the final report. The AASM wrote, “AHRQ conclusions do not reflect the totality of available evidence, and misinterpretation of the draft report could have detrimental repercussions for the millions of Americans with OSA.” The letter pointed out that the AHRQ report did not look at measures of excessive sleepiness or blood pressure reduction to be clinically significant outcomes, and that it ignored the considerable level of evidence that CPAP use reduces motor vehicle accidents. The letter also acknowledged that AHI is a less than optimum surrogate of outcome,13 and that CPAP has a “Dose Response.”14,15 A direct quote from the AASM letter, “CPAP is an imperfect therapy, and like most treatments, adherence is variable. We propose at least two more appropriate approaches for examining a dose-response relationship between changes in AHI and any clinical outcome be considered.” The first involves examining the extent to which CPAP alleviates AHI, taking into consideration CPAP usage as a proportion of total sleep time; mean disease alleviation index16 and the effective AHI.17,18 The second involves examining the relationship between hours of CPAP use and improvements in clinical outcomes.19,20 The letter proceeded to discuss the ethical and practical reasons that randomized controlled trials are difficult to conduct when it comes to sleepy patients, pointing out that non-sleepy patients are typically less adherent in the long-term and as such, the conclusions regarding endpoints may not apply to sleepy patients that would be more likely to remain adherent.21

A Paradigm Shift: From Gold Standard to Optimized Care

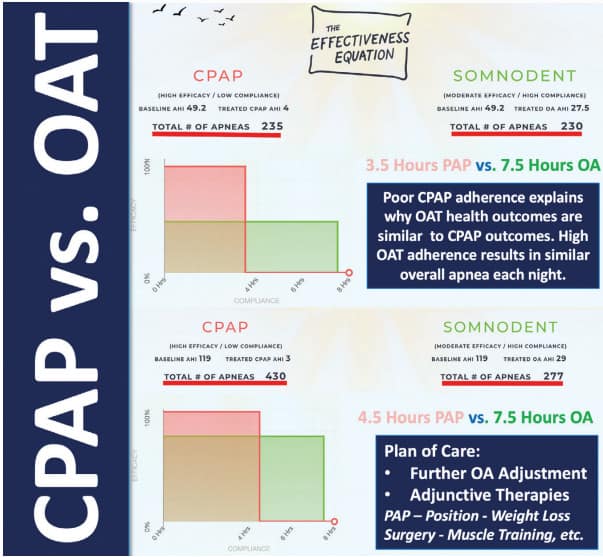

It is interesting that the AASM is now recommending alternative metrics when evaluating outcomes for establishing CPAP effectiveness; one that considers adherence, and nightly hours of use, rather than reduction in AHI. The SomnoMed Effectiveness Equation (SomnoMed, Plano, TX) is a software product that compares OAT and CPAP based on these exact variables with the intention of establishing a more realistic understanding of how much benefit a patient is receiving from both therapies. It enables clinicians to consider the impact treatment adherence can have on OAT outcomes which can be comparable or even superior to CPAP, even though the OAT resulted in residual AHI (Figure I).

The AHRQ report could be considered a “call to action” for myriad issues:

- Ensure better research

- Use more meaningful markers than AHI

- Consider adherence, hours of nightly use and actual effectiveness in the field

- Evaluate treatment alternatives that patients are more likely to comply with

- Collaborate with other care providers to optimize patient outcomes

Philips Recall and Physician-Dentist Collaboration

Currently, the world is dealing with the recall of an estimated 3-4 million bi-level PAP, CPAP, and mechanical ventilator devices manufactured by Philips.22 The recall is in response to potential health risks associated with the sound abatement foam component used in these devices. This foam may break down, resulting in particulate matter and volatile organic compounds (VOC) that can then circulate through the CPAP tubing. Philips has announced that potential risks to patients include skin, eye and respiratory tract irritation, inflammation, headache, asthma, adverse effects to other organs, and toxic carcinogenic effects.23 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has classified the recall of Philips’s breathing devices and ventilators as Class 1, the most serious type of recall, stating that use of these devices may cause serious injuries or death.24

For those patients affected by the Philips recall, the FDA recommends talking to your health care provider regarding a suitable treatment for your condition, which may include:25

- Stopping use of your device

- Using another similar device that is not part of the recall

- Utilizing alternative treatments for sleep apnea, such as positional therapy or oral appliances, which fit like a sports mouth guard or an orthodontic retainer.

- Initiating long term therapies for sleep apnea, such as losing weight, avoiding alcohol, stopping smoking, or, for moderate to severe sleep apnea, considering surgical options.

- Continuing to use your affected device, if your health care provider determines that the benefits outweigh the risks identified in the recall notification.

Philips is now discouraging the use of ozone-related cleaning products due to concerns regarding the potential degradation of the sound abatement foam.22

In an effort to find a solution for patients in need of immediate therapy where replacement devices are not available in a timely manner, a trained dentist can provide an interim oral appliance such as a myTAP (Airway Management, Inc., Farmers Branch, TX). (See Figure II) Once the patient receives their replacement device, this oral appliance could continue to be useful as back-up therapy. However, for some patients, a well-chosen, long-term custom appliance may be preferred therapeutic modality. This current situation could uncover those semi-adherent CPAP patients that may benefit from the opportunity to trial OAT. For those patients that experience residual apnea with their appliance, a well-trained dentist will be able to navigate the patient through various adjunctive therapies. These include sleep position,26 head elevation,27 weight loss28 myofunctional therapy29 and increasing fitness levels,30 all of which have the potential to further normalize the AHI.

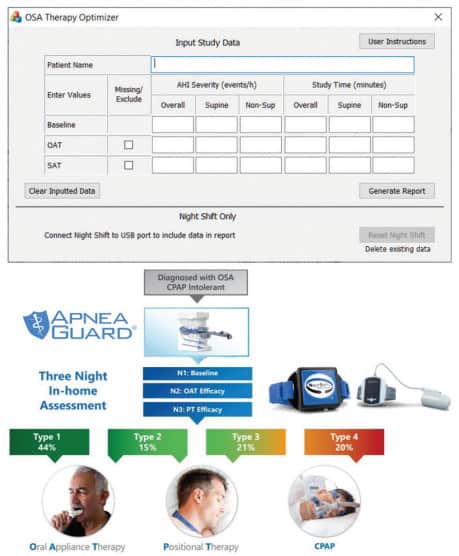

Dan Levendowski recently introduced software which was designed based on research findings to select the optimum therapy alternative for patients impacted by the Philips recall.31 The software allows input of a 3-night sleep study evaluation. Night one is a baseline study. Night two is a study with use of a trial appliance such as the ApneaGuard (Advanced Brain Monitoring, Carlsbad, CA), and the third night is a study with use of positional therapy such as the NightShift (Advanced Brain Monitoring Carlsbad CA). The software automatically analyzes the input data and determines if patient care would be optimized by use of OAT, combining OAT and positional therapy, positional therapy alone, or PAP therapy alone. (See Figure III) Considering the current shortage of replacement devices, it would be beneficial to pre-determine exactly which patient will respond exclusively to PAP therapy, allowing for efficient and reliable use of the heavily restricted PAP inventory.

COVID-19 and CPAP Mask Leaks

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the fact that even well-fitting CPAP masks leak, leading to concerns of spreading infection throughout the household for those that are infected with COVID-19. AASM guidance recommends that COVID-19 positive CPAP patients speak to their physician about assessing the risks and benefits of continuing CPAP use.32 AADSM guidance currently recommends that OAT could be considered an effective alternative to CPAP for these patients. They underscore that OAT does not share any of the aerosol concerns and is also much easier to disinfect daily, and recommends that under the supervision of a physician, OAT should be prescribed as a first-line therapy for sleep apnea during the COVID-19 pandemic.33

What Dentistry Has to Offer

In the United States there are 7,500 board-certified sleep specialists.9 In contrast, the ADA website reports that in 2020 there were 201,117 dentists working in the United States,34 However, only 800 dentists currently meet the requirements as a Diplomate of the ABDSM.35 The AADSM provides a “Qualified Dentist” designation, which requires dentists to successfully complete the AADSM’s Mastery Course I.36 This designation is for any dentist that would like an official credential demonstrating basic competency in dental sleep medicine and also provides a stepping-stone for those dentists interested in becoming a Diplomate of the ABDSM. The AADSM reports a total of 1,775 Diplomates and Qualified Dentists as of the writing of this article; a small fraction of the total number of dentists in the U.S. Clearly, dentistry has a massive workforce to offer, but more motivation is required to attract dentists to this field. Establishing a more collaborative workflow between physicians and dentists is necessary to improve access to care.

Working in collaboration with a physician, a well-trained dentist is ideally positioned to have a significant impact on all levels; screening, management, and follow-up. 80% of Americans have a dentist of record37 and 79% of Americans visit their dentist every 2-3 years.34 Patients are accustomed to regularly visiting their dentists for follow-up appointments and a Physician-Dentist Collaboration could help fill the current need expressed by Doctors Seixas and Koshla and provide the required “army” they alluded to.

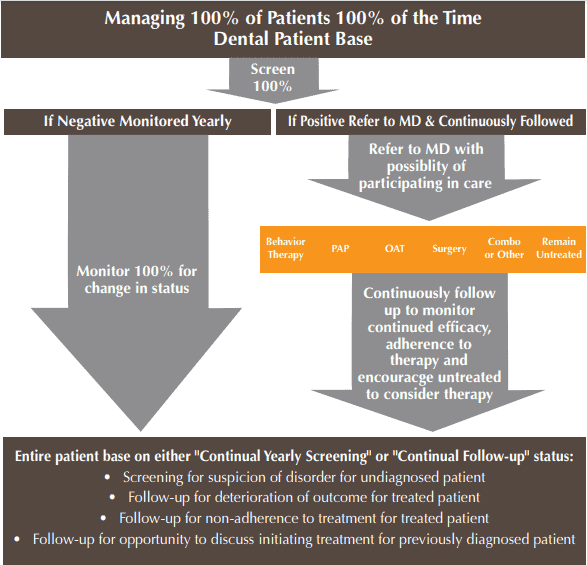

In 2017, the ADA published guidance mandating that dental offices screen their adult and pediatric patients for airway disorders, establishing both referral and management standards of practice.1 Dentistry provides direct professional access to patients, with the ability to screen, offer therapy, and the necessary follow-up resources. Active screening of each patient could reduce undiagnosed levels of SDB dramatically. Dr. Seixas states that the AASM is looking for “new solutions of care and workflow.” The AADSM is an evidence-based professional organization that has published guidance that many dental licensing bodies follow. Oral appliance therapy has been demonstrated to be an effective, highly successful, conservative therapy. Physician-Dentist Collaboration could provide the PAP non-adherent patients easy access to OAT and also aid in uncovering the many undiagnosed sufferers, guiding them to appropriate physician-supervised collaborative therapy. (See Figure IV) Mobilizing the entire dental workforce to conform to the 2017 ADA guidance would exponentially improve access to care.; to provide screening, referral, OAT (when appropriate and by physician prescription), and follow-up. In fact, regular dental visits help to facilitate these crucial follow-up appointments.

Despite the 2017 ADA guidance,1 California-based Glidewell Dental Lab, reported by Frost and Sullivan4 to be the largest provider of oral appliances for snoring and sleep apnea in the United States, indicates that 20% of their customers treated a snoring and sleep apnea patient in 2019. This number grew by 25% year over year from 2018, spurred by significant clinical education initiatives. However, even with the large number of cases that were shipped, less than 1% of accounts prescribed 10 appliances or more for the year, signifying an underserved need when compared to the estimated number of patients suffering from some form of SDB.

Is Dentistry Adequately Trained?

A study of SDB education in 49 US dental schools published in 2012 found the mean time spent teaching SDB to be 0.5 h for first year, 0.64 h for second year, 1.81 h for third year and 0.97 h for fourth year in the 37 schools that actually provided some curriculum.38 Nearly a decade later, the level of SDB education dentists have acquired upon graduating dental school has not materially increased. A personal survey of recent University of Toronto, Canada dental school graduates found that they completed their degree requirements with only approximately 1 hour of education regarding SDB.

Dentists who opt to practice DSM should first obtain adequate post-dental school training to achieve competency. It is unnerving that the 2017 ADA guidance was not more impactful. Lives could have been saved if more clinicians followed this guidance. However, the DSM world is full of obstacles such as Medicare rules, insurance coverage criteria, clinical competency, internal team buy-in, and the strong physician bias for CPAP. All of these make entry into DSM more challenging. However, physician resistance to OAT may shift due to the AHRQ draft and the Philips recall. It is likely that abiding ADA guidance will become easier to entertain for a dentist new to DSM once the wall of physician bias has been dismantled, thus attracting more dentists to enlist in the army to battle SDB.

Are Dentistry and OAT Worthy?

Clearly, PAP is superior at reducing AHI.39 However, when comparing adherence, OAT is superior.2 This results in an unexpected phenomenon. Although the following is rarely stated or even acknowledged by physicians, there is overwhelming evidence that health outcomes with OAT compare very favorably to those of PAP. This is found to be the case for objective measures of health outcomes,40 measures of functional outcomes,41 hypertension outcomes,42 and cardiovascular mortality outcomes.43 This may be in part explained by the “Dose Response” relationship observed with PAP use. One study documented that the number of hours PAP is worn nightly is related to both cerebrovascular events and development of hypertension.14 Along these same lines, various measures of sleepiness as documented by the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Score, and the Multiple Latency Score have also been shown to be related to hours of nightly CPAP use.15 When considering side effects, the frequency and intensity of OAT side effects are similar to reports of PAP side effects.44 A crossover comparison study between PAP and OAT documented that patients preferred OAT in all aspects evaluated.45 In fact, multiple studies have revealed that patients prefer OAT to PAP,46 and it is this preference that may translate to more hours of oral appliance use. It is not always possible for patients to get the recommended amount of sleep, however, OAT is most therapeutically effective when patients sleep 7 hours or more,46 so qualified dentists must educate the patient on the importance of obtaining sufficient sleep nightly. Objectively documented OAT adherence studies have found OAT adherence to be 86.1%47 and 91.2%.48 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature evaluating factors that influence OAT adherence found a weak relationship between objective adherence and patient and disease characteristics, such as age, sex, obesity, apnea hypopnea index, and daytime sleepiness. However, non-adherent patients reported more side effects with OAT than adherent users and tended to discontinue the treatment within the first 3 months. Additionally, custom fabricated oral appliances were preferred, and had increased adherence in comparison with non-custom appliances.49

As mentioned above, ADA guidance recommends that we screen both our adult and pedo patients for SDB and then through collaborative efforts with physicians, surgeons, and other appropriate specialists, participate in the care and follow-up of those patients.1 For patients that screen positive for SDB, a referral to a medical specialist is required for evaluation and diagnosis. In Canada, the prevalence of adults with, or at high risk of having sleep apnea is approximately 26.8%, approximately ¼ of the adult patient base.50

We will review the potential management of this group under the following scenarios:

- Dental Diagnostic Testing Allowed

- Dental Diagnostic Testing Not Allowed

- Previously Diagnosed Patients

- Immediate Need and Delay to Treatment.

Dental Diagnostic Testing Allowed

A dentist can order or dispense a multiple night Home Sleep Test (HST) with interpretation by a board-certified sleep physician. A multiple night study is important to account for night-to-night variability.51,52 HST devices such as the NightOwl (Ectosense, Belgium) facilitate multi-night sleep testing, but no data is provided regarding body position, airflow, or breathing effort. Level III HST devices like the WatchPAT (Itamar Medical Limited, Israel) and NOX T3 (NOX Medical, Iceland) can be used to obtain multiple night studies and they do provide position, airflow, and breathing effort data. A well-trained dentist should be able to discuss the various treatment options recommended by the board-certified sleep physician that interpreted the sleep study and provided the diagnosis. Whichever therapy implemented, the dental office should monitor adherence to treatment and regularly report to the prescribing physician.

Dental Diagnostic Testing Not Allowed

A patient who has screened positive for sleep apnea should be referred to a board-certified sleep physician. In some jurisdictions, this will require an intermediary referral to their primary care physician. They will arrange the appropriate sleep testing and complete the interpretation and provide the diagnosis and appropriate prescription. The physician then meets with the patient to discuss treatment options.

Previously Diagnosed Patients

Dental follow-up appointments should review and confirm the patient’s continued adherence to treatment. Patients are commonly considered CPAP adherent if they wear their device 4 hours/night, 5 nights/week. However, they should be coached to wear their CPAP a minimum of 5-6 hours/night which is closer to the levels required to improve measures of sleepiness and hypertension.14,15 For patients unable to establish this level of CPAP adherence, a conversation should focus on efforts to increase adherence, and/or the possibility of adding adjunctive therapies that may increase CPAP adherence, or alternative therapies such as OAT that the patient may find easier to comply with. When one considers that approximately 83% of patients have dropped out of CPAP use by year five,6 it is easy to imagine that regular dental screening would uncover a sizable group of non-adherent former CPAP patients.

Immediate Need & Delay to Treatment

The uneven distribution of board-certified sleep physicians sometimes results in lengthy waiting periods to initiate treatment. Although controversial, and outside the scope of current guidelines, these patients may benefit from an interim treatment, or “provisional” device while awaiting access to a board-certified sleep physician. A knowledgeable dentist could dispense a HST and while awaiting a diagnosis and treatment recommendations proceed with an interim oral appliance such as a myTAP temporary appliance. It is important to acknowledge that this need is very real for a segment of the general population, and that it is important to have this discussion rather than pretend the issue does not exist. However, to solve this problem together, one first needs to be liberated of the concept that dentistry is a Trojan Horse. Instead, it must be viewed as an army of allied troops ready, willing, and able to help.

A Vision for the Future: Alberta, Canada Model of Care

Guidance for the Alberta, Canada model of care, published in 2019, is the result of all stakeholders coming together to establish a standard for dentists who provide SDB treatment to adult and pediatric patients.53

This guidance clearly indicates that dentists providing OAT to manage SDB must be properly trained and that SDB can only be diagnosed by a sleep medicine physician. They discuss a multidisciplinary collaborative approach in which a physician and dentist work collaboratively to provide an effective workflow, where patients with undiagnosed SDB can be screened, diagnosed, and treated with appropriate treatment modalities.

In Alberta, a qualifying dentist can order, request, prescribe, own and dispense equipment for sleep testing for oral appliance calibration, and for submission to a physician for screening and diagnosis of SDB.

Before providing OAT, a dentist must first complete comprehensive record taking, obtain informed consent and inform the patient about OAT and associated side effects, CPAP therapy and associated side effects, surgical alternatives, sleep behavioral therapy and all alternative and appropriate adjunctive therapies. A written prescription from a physician is required prior to proceeding with OAT, and therapy should involve a custom, titratable appliance. The Alberta guidance specifically states that “Use of non-custom or temporary mandibular repositioning devices as a diagnostic tool is not recommended.”

Ongoing monitoring, follow-up testing, and evaluation of treatment for adults and pediatric patients is mandated, and pediatric treatment requires appropriate screening and confirmative diagnosis and involvement of the pediatric sleep team, including a sleep medicine physician.

No Trojan Horse Here!

All this bears well for the future of oral appliance therapy. The calls to action resulting from the AHRQ draft report illuminate CPAP adherence issues, thus challenging the Gold Standard moniker and polarized therapy approach. All parties acknowledging the need for better research, the shortcomings of using AHI as an outcome marker, the importance of considering treatment adherence, and the evaluation of treatment alternatives that patients are more likely to comply with bodes very well for OAT as a viable treatment alternative. The Physician-Dentist Collaboration has been exemplified by how dentistry has positioned itself to help patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and PAP recall. The Alberta, Canada model stands as an example of Physician-Dentist Collaboration at work. Finally, regarding that army Dr. Seixas rallied for in his podcast… Here We Are – Together We’re Stronger!

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Dr. Shouresh Charkhandeh for critically reviewing this article prior to publication.

Besides the need for physician-dentist collaboration, Dr. Viviano has written for DSP about a 3D-printed nylon sleep apnea appliance. Read about its unique set of characteristics. https://dentalsleeppractice.com/enhancing-retention-of-a-3-d-printed-nylon-sleep-apnea-appliance/

References

- American Dental Association [ADA]. Policy statement on the role of dentistry in the treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders. Adopted by 2017 House of Delegates [Internet]. Chicago, IL: ADA; 2017. Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/The-Role-of-Dentistry-in-Sleep-Related-Breathing-Disorders.pdf?la=en

- Sutherland K, Phillips CL, Cistulli PA. Efficacy vs. effectiveness in the treatment of OSA: CPAP and oral appliances. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine 2015;2(4):175–181

- Benjafield AV, et al., Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature- based analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2019 Aug 1;7(8):687-98.

- Frost & Sullivan. The price of a good night’s sleep: Insights into the US oral appliance market [Internet]. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2017. Available from: https://www.columbussleepcenter. com/assets/docs/frost-and-sullivan.pdf

- Bartlett D, Wong K, Richards D, et al. Increasing adherence to obstructive sleep apnea treatment with a group social cognitive therapy treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep 2013;36:1647–54.

- Weaver TE, Sawyer A. Management of obstructive sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2009;21:403–12.

- Vijay Kumar Chattu et al., Insufficient Sleep Syndrome: Is it time to classify it as a major noncommunicable disease? Sleep Sci Mar-Apr 2018;11(2):56-64. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20180013.

- Frost & Sullivan. “Vital Signs, The Price of a Good Night’s Sleep: Insights into the US Oral Appliance Market” Commissioned by the AASM. January 2015

- org website

- Watson NF, Rosen IM, Chervin RD, Board of Directors of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The past is prologue: the future of sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(1):127–135.

- AHRQ DRAFT Report: Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea 2021

- AASM Letter RE: Draft Technology Assessment – “Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. April 23, 2021

- Malhotra A, Ayappa I, Ayas N, et al. Metrics of Sleep Apnea Severity: Beyond the AHI. Sleep. 2021.

- Navarro-Soriano et al., Long-term Effect of CPAP Treatment on Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Resistant Hypertension and Sleep Apnea. Data From the HIPARCO-2 Study Arch Bronconeumol. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2019.12.006

- Weaver TE; Maislin G; Dinges DF et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. SLEEP 2007;30(6):711-719

- Grote L, et al. Therapy with nCPAP: incomplete elimination of Sleep Related Breathing Disorder. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(5):921-7.

- Bakker JP, et al. Adherence to CPAP: What Should We Be Aiming For, and How Can We Get There? Chest. 2019;155(6):1272-87.

- Bianchi MT, Alameddine Y, Mojica J. Apnea burden: efficacy versus effectiveness in patients using positive airway pressure. Sleep Med. 2014;15(12):1579-81.

- Antic NA, Catcheside P, Buchan C, et al. The effect of CPAP in normalizing daytime sleepiness, quality of life, and neurocognitive function in patients with moderate to severe OSA. Sleep. 2011;34(1):111-9.

- Weaver TE, Maislin G, Dinges DF, et al. Relationship between hours of CPAP use and achieving normal levels of sleepiness and daily functioning. Sleep. 2007;30(6):711-9.

- Cistulli PA, Armitstead J, Pepin JL, et al. Short-term CPAP adherence in obstructive sleep apnea: a big data analysis using real world data. Sleep Med. 2019;59:114-16.

- Masse, JF. On the Philips recall and the professionalism of dental sleep medicine. J Dent Sleep Med. 2021;8(3)

- Najib T. et al., Position Statement from the Canadian Thoracic Society, Canadian Sleep Society and the Canadian Society of Respiratory Therapists Philips Respironics Device Recall Version 1.0 – July 9, 2021. Emailed July 19, 2021 at 11:23 am EST

- Reuters Website. FDA classifies Philips ventilator recall as most serious. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/fda-classifies-philips-ventilator-recall-most-serious-2021-07-22/

- FDA Website. Certain Philips Respironics Ventilators, BiPAP, and CPAP Machines Recalled Due to Potential Health Risks: FDA Safety Communication. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/certain-philips-respironics-ventilators-bipap-and-cpap-machines-recalled-due-potential-health-risks

- Takaesu Y, Tsuiki S, Kobayashi M, Komada Y, Nakayama H, Inoue Y. Mandibular advancement device as a comparable treatment to nasal continuous positive airway pressure for positional obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(8):1113–1119.

- Souza et al., The influence of head-of-bed elevation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. June 24, 2017; DOI 10.1007/s11325-017-1524-3

- PE Peppard et al, Longitudinal Study of Moderate Weight Change and Sleep-Disordered Breathing. JAMA December 20, 2000. Vol 284 No 23

- Camacho M, Certal V, Abdullatif J, Zaghi S, Ruoff CM, Capasso R, Kushida CA. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SLEEP 2015;38(5):669–675.

- Maciel Dias de Andrade and Pedrosa, The role of physical exercise in obstructive sleep apnea. J Bras Pneumol. 2016 Nov-Dec; 42(6): 457–464

- Levendowski DJ, et al. Criteria for oral appliance and/or supine avoidance therapy selection criteria based on outcome optimization and cost-effectiveness. J Med Economics 2021; 24(1)

- org website

- Schwartz D, Addy N, Levine M, Smith H. Oral appliance therapy should be prescribed as a first-line therapy for OSA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine. 2020 May;7(3):1.

- ADA Website

- org website

- org website

- 2019 NADP Dental Benefits Report

- Simmons MS., Pullinger A., Education in sleep disorders in US dental schools DDS programs. Sleep Breath (2012) 16:383–392

- Schwartz, M. et al. Effects of CPAP and mandibular advancement device treatment in OSA patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath 2018: 22, 555–568

- Philips, Gozal & Malhotra, What is the Future of Sleep Medicine in the United States AJRCCM 2015: 192(8), 915-917

- Gagnadoux et al., Titrated Mandibular Advancement vs. Positive Airway Pressure for Sleep Apnea. European Respiratory Journal, 2009: 34(4), 914-920

- Bratton et al., CPAP vs Mandibular Advancement Devices and Blood Pressure in Patients With OSA: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2280-2293

- Anandam et al., Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnoea treated with continuous positive airway pressure or oral appliance: An observational study. Respirology, 2013: 18(8),pp1184-1190

- Gagnadoux et al. Titrated mandibular advancement versus positive airway pressure for sleep apnoea Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 914–920

- Yamamoto et al., Crossover comparison between CPAP and mandibular advancement device with adherence monitor about the effects on endothelial function, blood pressure and symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea Heart Vessels 2019: 34, 1692–1702

- Sutherland K, Phillips CL, Cistulli PA. Efficacy vs. effectiveness in the treatment of OSA: CPAP and oral appliances. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine 2015;2(4):175–181

- Dieltjens M, Braem MJ, Vroegop AVMT, et al. Objectively measured vs self-reported compliance during oral appliance therapy for sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2013;144(5):1495-1502. doi:10.1378/CHEST.13-0613

- Vanderveken OM, et al. Objective measurement of compliance during oral appliance therapy for sleep-disordered breathing. Thorax. 2013;68(1):91-96. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201900

- Tallamaraju H, Newton JT, Fleming PS, Johal A. Factors influencing adherence to oral appliance therapy in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(7):1485–1498.

- Jessica Evans, et al. The Prevalence Rate and Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Canada. Slide Presentations: Sunday, October 31, 2010 | October 2010 Chest. 2010;138(4_MeetingAbstracts):702A. doi:10.1378/chest.10037

- Daniel Levendowski, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea variability measured in-lab versus in-home on sample size calculations. International Archives of Medicine. 2009, 2:2 doi:10.1186/1755-7682-2-2

- Prasad B., et al. Short-term variability in apnea-hypopnea index during extended home portable monitoring. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(6):855–863.

- Alberta Dental Association and College. Standard of Practice: Non-surgical Management for Sleep Disordered Breathing. 2019

Dr. Viviano obtained his credentials from the University of Toronto in 1983. His clinic is limited to managing sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-related bruxism. He is a Credentialed Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and has lectured internationally, conducted original research, and authored original articles on the management of sleep-disordered breathing. His clinic is the first Canadian facility accredited by the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine and he is Clinical Director of the Sleep Disorders Dentistry Research and Learning Centre. Dr. Viviano also hosts the SleepDisordersDentistry LinkedIn Discussion Group and conducts dental sleep medicine CE programs for various levels of experience, including a 4-day mini residency. Dr. Viviano’s Class and Cloud Based CE programs can be found on SDDacademy.com, and he can be reached at (905) 212-7732 or via the website

Dr. Viviano obtained his credentials from the University of Toronto in 1983. His clinic is limited to managing sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-related bruxism. He is a Credentialed Diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and has lectured internationally, conducted original research, and authored original articles on the management of sleep-disordered breathing. His clinic is the first Canadian facility accredited by the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine and he is Clinical Director of the Sleep Disorders Dentistry Research and Learning Centre. Dr. Viviano also hosts the SleepDisordersDentistry LinkedIn Discussion Group and conducts dental sleep medicine CE programs for various levels of experience, including a 4-day mini residency. Dr. Viviano’s Class and Cloud Based CE programs can be found on SDDacademy.com, and he can be reached at (905) 212-7732 or via the website  John Bouzis, DDS, is a member of the American Dental Association, the Natrona County Dental Society, the Wyoming Dental Association, the Academy of General Dentistry, the Association for the Study of Headache, Fellow in the International College of Cranio Mandibular Orthopedics, and the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. His education and affiliations allow him to be an asset to those seeking information and treatment for sleep apnea. Dr. Bouzis has hundreds of hours of continuing education devoted to the treatment of TMJ, Jaw Disorders, Headaches and Migraines and, most recently, Sleep Medicine and the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. When Dr. Bouzis isn’t treating patients at his office in Casper, WY, he enjoys racing bicycles, racquet ball, golf, sports conditioning, and technology – especially the technical aspects of modern dentistry and its impact on patient care and comfort.

John Bouzis, DDS, is a member of the American Dental Association, the Natrona County Dental Society, the Wyoming Dental Association, the Academy of General Dentistry, the Association for the Study of Headache, Fellow in the International College of Cranio Mandibular Orthopedics, and the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. His education and affiliations allow him to be an asset to those seeking information and treatment for sleep apnea. Dr. Bouzis has hundreds of hours of continuing education devoted to the treatment of TMJ, Jaw Disorders, Headaches and Migraines and, most recently, Sleep Medicine and the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. When Dr. Bouzis isn’t treating patients at his office in Casper, WY, he enjoys racing bicycles, racquet ball, golf, sports conditioning, and technology – especially the technical aspects of modern dentistry and its impact on patient care and comfort.