This article by Dr. Richard B. Dunn, Jessica Turner, CDA, and David Walton, CDT, discusses a technique with a Mandibular Advancement Device to bring effective and comfortable treatment to edentulous patients.

by Richard. B. Dunn, DDS, MS, D.ABDSM; Jessica Turner, CDA; and David Walton, CDT

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a major medical problem throughout the world. It has been estimated to affect 15-30% of male adults and 5-15% of female adults.1,2 In a more recent publication, it is estimated that 50% of men and 23% of women aged 45-85 years have moderate to severe OSA, defined as 15 or more breathing disturbances per hour of sleep.3 Furthermore, the estimated prevalence of OSA has increased by 14% to 55% over the past two decades.4 The prevalence of OSA is therefore significant and increasing with greater obesity and aging of populations.5 Moreover, according to the American Dental Association more than 36 million Americans are edentulous. This article presents a technique to address OSA in this patient population using oral appliance therapy.

OSA is a disorder characterized by recurrent, transient narrowing (hypopnea) and collapse (apnea) of the upper airway during sleep. These breathing disturbances cause frequent oxygen desaturations (nocturnal hypoxemia) and sleep fragmentation with recurrent arousals from sleep. When left untreated there is an extensive list of symptoms as well as adverse health consequences of daytime sleepiness, decreased concentration, fatigue, irritability, and memory loss,6 reduced quality of life,7 increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,8 cardiovascular disease,9,10 metabolic disorders,11 cognitive impairment,12 depression13 and cancer.14 In addition, studies have shown that patients suffering from edentulism are more likely to develop OSA. Edentulism leads to a decrease in size and tone of the pharyngeal musculature and reduction of the retropharyngeal and posterior airway space.15,16 Studies have inferred that pharyngeal expansion can be accomplished with a Mandibular Advancement Device (MAD) and the increased volume was most pronounced in the velopharynx region.17 A great challenge faced by dental sleep medicine (DSM) clinicians is to provide effective and comfortable treatment with MAD therapy for edentulous patients. DSM providers are seeing more of these patients referred by physicians due to the increased number of people with OSA and non-compliance or inability of patients to use CPAP. Lack of teeth and anchorage for the MAD can be very challenging. Some qualified dentists will not treat these patients for a variety of reasons including reduced retention and comfort of the MAD and difficulty in obtaining accurate protrusive and bite records. However, for many of these patients, dental sleep clinicians may be their last chance to have their OSA treated. An excellent option for the edentulous patient is the use of implants to help anchor the MAD but patients may not be able to afford them or are not good candidates due to lack of bone or other medical conditions. Some clinicians prefer to make the MAD to fit over the existing denture(s). Impression techniques are relatively simple and the dentures can be used to establish the bite relationships, vertical dimension, and horizontal range of protrusion. This combination may not be successful due to the increased thickness, bulk, crowding, and vertical opening it creates which can be counter-productive to the treatment of the underlying OSA. The patient is essentially wearing four oral prosthesis (upper and lower dentures, along with upper and lower oral sleep devices) which is likely to decrease tongue space perhaps worsening, not improving, OSA. If the MAD is to be made to fit the edentulous ridge without the denture, it is difficult to accurately record the vertical dimension and protrusion of the appliance and communicate this to the lab correctly and effectively. Use of occlusal wax rims can be extremely challenging to set the correct incisal edge position and midline alignment to determine the protrusive start position. If the wax rim doesn’t accurately replicate the incisal edge of the denture, the dentist could take a protrusive bite at 3mm (for example) but could actually be advancing them much more, or much less, than the wax rim is showing. This could lead to unnecessary side effects and/or not increasing the pharyngeal space in the airway, rendering the oral sleep device ineffective.

This article will explain a new way to eliminate errors and construct an effective MAD for the treatment of the patient’s OSA. Clinical cases and photos will demonstrate this process.

Methods

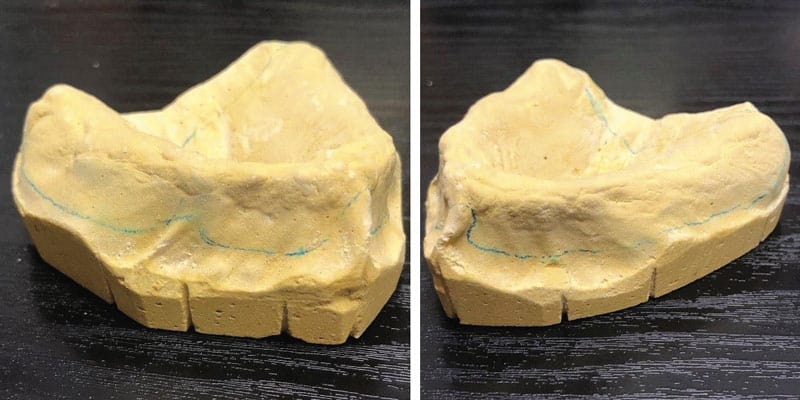

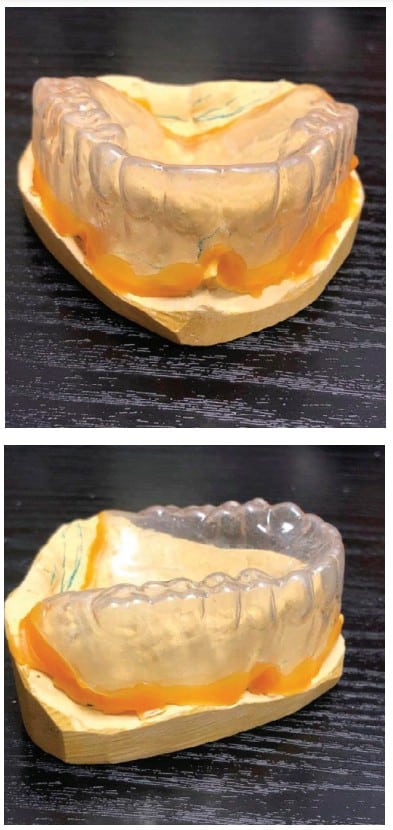

The cases demonstrate the construction of a MAD in an edentulous maxilla with teeth present in the mandible. The patient is wearing a full upper denture (FUD) which is retentive. Examination reveals adequate bone and alveolar ridge to support the maxillary component of the MAD. Impressions are taken of the mandible, edentulous maxilla and the existing FUD in the mouth. The impression of the edentulous maxilla should include all borders and extensions of the FUD for maximum retention of the OA (see Figure 1). The maxillary component of the MAD will be fabricated to fit directly over the edentulous maxilla (see Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C). Therefore, this needs to be a very accurate impression to ensure excellent fit, retention and comfort for the patient. With the patient wearing their FUD, records for the MAD can be obtained by standard techniques using a George Gauge to choose the starting position and desired vertical dimension of the appliance and record the maximum range of motion from most retruded to maximum protrusive positions. This eliminates the guess work previously described in obtaining an accurate protrusive position. After obtaining the protrusive bite records the impressions are poured up with good quality stone and trimmed when set. A suck down over the stone model of the FUD with 060-gauge material is done and carefully trimmed to fit accurately over the edentulous model with full extension to the borders. The suck down can then be held in place on the edentulous model with sticky wax or any other techniques preferred (see Figures 3A and 3B). This gauge material is used to obtain good definition of the FUD without being too thick to alter vertical dimension and to be sturdy enough to not distort by flexing when mounting. The edentulous model with attached suck down is then placed into the George Gauge bite and sent to the lab which will then place the opposing model in the bite and mount the case on a semi-adjustable articulator (see Figures 4A and 4B). When the mounting is set in the articulator the suck down can be removed from the maxillary model. The starting protrusive position, midlines and vertical opening of the appliance have now been accurately provided to the laboratory and construction of the appliance can begin. Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C demonstrate the MAD appliance intraorally. It’s important to note that there is often a misunderstanding between the clinician and the laboratory around transferring the dimensions of the denture to the sleep device. Unfortunately, it is not possible to take an impression of the denture and an impression of the oral cavity and lay one model over the top of the other.

It is also possible to make a MAD for a fully edentulous patient (Figure 4C) using the same process of using a suck down transfer record. However due to the lack of retention in the mandible, implants would be needed to attach the mandibular component of the Oral Appliance to gain adequate retention.

If the patient has implants present or if implants are to be placed, impressions are taken through standard techniques that will record the position of the implants to the lab. The use of 4 or more implants would be ideal for retention of the MAD but 2 would be the minimum. Communicate with the dental sleep lab about your intention to connect the sleep appliance component to the implants, type of attachments that will be used, and how much relief on the underside of the appliance you desire at each implant site. This will save chair time at the insertion appointment. The technique to connect the mandibular component of the MAD to the implants is similar to that used for an implant retained overdenture. The same procedures can be used if there are implants in the maxilla.

A common question asked is what fees should be charged for these procedures. This obviously needs to be determined by each clinician. The author chooses to not make additional charges for a MAD for an edentulous maxilla. Delegating some of the extra tasks to team members can mitigate the extra costs. Attaching a component of the MAD to implants can be a time consuming process so a fair fee needs to reflect time spent as well as components and materials needed. Our experience has been that patients are accepting of these additional fees when explained prior to treatment. This discussion should include the improved effectiveness, retention, and comfort of the sleep appliance with implant support.

After a combined 24 years working in dental sleep medicine, the authors believe this technique has great value when treating edentulous patients with OSA. We have had repeated clinical successes while reducing some of the clinical and production challenges previously encountered.

Check out this article on predicting, preventing, and managing complications with a Mandibular Advancement Device. https://dentalsleeppractice.com/mandibular-advancement-devices/

- YoungT, Palta M, Dempsey J, Peppard PE, Nicio FJ, Hia KM (2009) Burden of sleep apnea:rationale, design and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study, WMJ 108(5): 246-249.

- Peppani PF, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen FW, Hla KM. (2013) Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 177(9):1006-1014

- Lai V, Carberry J, Eckert D. Sleep Apnea Phenotyping: Implications for Dental Sleep Medicine. J Dental Sleep Med (2019): 6(2)

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hia KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177(9): 1006-1014.

- Nieto FJ, Peppard PE, Young T, Finn L, Hla KM, Farre R. Sleep-disordered breathing and cancer mortality: Results from the Wisconsin sleep cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 190-194

- Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep. Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009: 5(3) 263-276.

- Lacasse Y, Godbout C, Serios F. Health -related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnea. Eur Resp J. 2002; 19(3):499-503.

- Ellen RI, MarshallSC, Palayew M, Molnar FJ, Wilson KG, Man-Son-Hing M. Systemic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(02): 193-200.

- Hla KM, Young T, Hagen EW, et al. Coronary Heart Disease Incidence in Sleep Disordered Breathing; The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Sleep 2015;38(5):677-684.

- Rodine S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke. The Sleep Heart health Study.. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):269-277.

- Aurora RN, Punjabi NM. Obstructive sleep apnoae and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a bidirectional association. Lancet Resp Med, 2013;1(4):329-338.

- Osorio RS, Gumb T, Pirraglia E, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurlology. 2015;84(19):1964-1971.

- BaHammam AS, Kendzerska T, Gupya R, et al. Comorbid depression in obstructive sleep apnea: an underrecognized association. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(2):447-456.

- Marshall NS, Wong KK, Phillips CL, Liu PY, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Is sleep apnea an independent risk factor for prevalent and incident diabetes in the Bussolton Health Study? J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(1):15-20.

- Bucca C, Carossa S, Piuetti S, Gai V, Rolla G, Preti G. (1999). Edentulism and worsening of obstructive sleep apnea. Lancet. 353(9147): 121-122.

- Bucca C, Cicolin A, Brussino L, Arionti A, Graziano A, Erovigni F, Pera P, Gai V, Mutani R, Preti G, Rolla G, Carrosa S (2006) Tooth loss and obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Res 7:8.

- Tripathi A, Gupta A, Sarkar S, Tripathi S, Gupta N. (2015) Changes in upper airway volume in edentulous obstructive sleep apnea patients treated with modified mandibular advancement device. J of Prosthodontics: 1-7.

Richard B. Dunn, DDS, MS. D.ABDSM, went to Franklin & Marshall College, received a MS from Roswell Park Memorial Cancer Institute in Head & Neck Cancer, and his dental degree from NYU College of Dentistry. He was nominated for Fellowship in The American College of Dentists and the Pierre Fauchard Academy. He is a Diplomate of The American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and serves as a Director of the ABDSM and is on the Executive Committee. Dr. Dunn has been practicing Dental Sleep Medicine for over 13 years and practices in a team approach with physicians, dentists, and dental sleep labs. He is the owner of Chemung Family Dental in Elmira, New York.

Richard B. Dunn, DDS, MS. D.ABDSM, went to Franklin & Marshall College, received a MS from Roswell Park Memorial Cancer Institute in Head & Neck Cancer, and his dental degree from NYU College of Dentistry. He was nominated for Fellowship in The American College of Dentists and the Pierre Fauchard Academy. He is a Diplomate of The American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and serves as a Director of the ABDSM and is on the Executive Committee. Dr. Dunn has been practicing Dental Sleep Medicine for over 13 years and practices in a team approach with physicians, dentists, and dental sleep labs. He is the owner of Chemung Family Dental in Elmira, New York. Jessica Turner is a Certified Dental Assistant in NYS and has assisted Dr. Dunn for the past 10 years in overseeing the Sleep Department at Chemung Family Dental. She is extremely focused on the sleep patients and their care and has dedicated herself to continuing education and clinical experience in Dental Sleep Medicine.

Jessica Turner is a Certified Dental Assistant in NYS and has assisted Dr. Dunn for the past 10 years in overseeing the Sleep Department at Chemung Family Dental. She is extremely focused on the sleep patients and their care and has dedicated herself to continuing education and clinical experience in Dental Sleep Medicine. Originally from the UK, David Walton graduated from the Royal College of Surgeons as a Clinical Technician treating patients for dentures before moving to New York where he co-founded Respire in 2010. Over the last 13 years, David has spearheaded the growth of Respire to become one of the leading oral sleep devices in the industry and recently led the company through a successful acquisition with Dynaflex where he continues to support future innovation.

Originally from the UK, David Walton graduated from the Royal College of Surgeons as a Clinical Technician treating patients for dentures before moving to New York where he co-founded Respire in 2010. Over the last 13 years, David has spearheaded the growth of Respire to become one of the leading oral sleep devices in the industry and recently led the company through a successful acquisition with Dynaflex where he continues to support future innovation.