Dr. Barry Glassman and Dr. Don Malizia note that anterior midpoint stop appliances may decrease the likelihood of developing joint pain. Read their insights here.

Less Adjustments and Less Forces

by Barry Glassman, DMD, and Don Malizia, DDS

In terms of preventing major cardiovascular accidents, the use of oral appliance therapy (OAT) has been shown to be as effective as CPAP use in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OAT effectiveness has been demonstrated as potentially effective for all levels of OSA severity – mild, moderate, and severe.1

Positive airway pressure, in its many forms, has long been heralded as the “gold standard” of care for OSA. The introduction of the smart card in CPAP raised the consciousness of the medical community to the compliance issue. Over time the term “effective AHI” was developed to consider the actual AHI during a full evening that combines the AHI that occurs when the CPAP is being used with the AHI that occurs when the CPAP has been removed during sleep.2 The documented, untoward effects of CPAP that may lead to poor compliance include discomfort from the mask, headaches from the straps, infections from poor cleaning, and bloating. The less obvious untoward effects of craniofacial changes that in some cases were quite severe are also now exposed.3

The introduction of oral appliances to the medical community at the end of the 20th century was not impressive. The monoblocs used by dentists were bulky and non-titratable, leading to inconsistent results with limited compliance and frequent side effects of joint pain and tooth movement. It wasn’t until 1995 when Schmidt-Nowara published his landmark paper suggesting that oral appliances could be successful in mild to moderate sleep apnea that OAT began to gain favor.4 In 1999 he published a second paper reporting oral appliance success in severe sleep apnea cases. Unfortunately, that paper never received the notice or fanfare that the first paper did.5 Consequently, to this day, many believe that oral appliances should only be used in mild to moderate OSA cases.

Not only were these early appliances rather ineffective, but they frequently resulted in the untoward side effects of tooth movement and joint pain. These complications were exaggerated and used as additional reasons to discourage the use of oral appliances. While there are those who continue to suggest that a depth of knowledge of TMJ function and treatment of joint pain is required in order to treat sleep disturbed breathing with OAT, the truth is that many dentists without that depth of knowledge continue to treat many patients very successfully. In fact, it is noted that joint complications are uncommon and often overstated.6

An NTI is an appliance prescribed by thousands of dentists to control nocturnal parafunctional forces. The NTI has no posterior support and only a midpoint anterior contact. Despite the common contention that the lack of posterior support will lead to increased joint pain and other complications, Blumenfeld, et al published results of an independent provider-based survey involving the use of an anterior midpoint stop design in 5,807 patients. The results demonstrated a high degree of success with the appliance for treatment of orofacial pain and favorable patient outcomes. Complications were very low in this large cross-sectional sample, and the appliance actually resolved joint pain as opposed to causing pain in many instances.7

A Brief History of Anterior Midpoint Stop Appliances

Costen, in 1934, postulated that posterior contact was necessary for “joint support.” Costen was an otolaryngologist who reported 12 cases of decreased joint pain when vertical dimension was increased.8 The need for posterior contact remained a prevailing concept, and several temporomandibular joint gurus based their treatment protocols on occlusion and balanced posterior contacts.

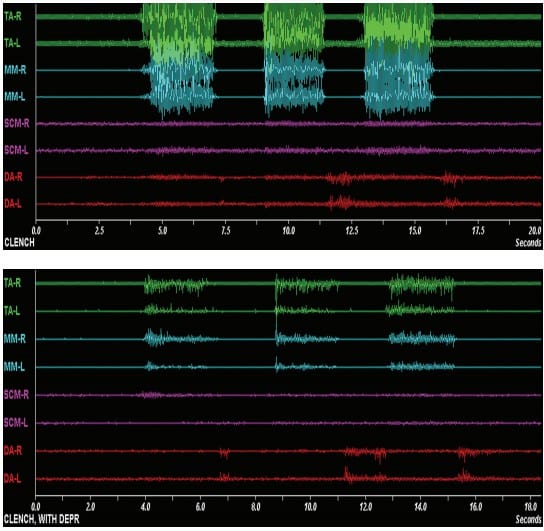

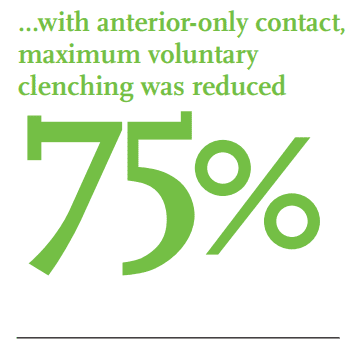

In 1979 Hylander, an anthropologist and anatomist, measured joint load on a dry skull while applying force at various points along the mandible. Nitzan cites his proposal that the more posterior the contact, the lower the force to the joint.9 However, it has since been demonstrated that while this may be the case on a dry skull, it is not the case in vivo. Miralles measured EMGs which revealed that with anterior-only contact, maximum voluntary clenching was reduced by 75% in the anterior temporalis and 55% in the masseter.10 In 2003, Hattori technically calculated joint load with a finite element analysis, demonstrating with shorter arches that moving the occlusal contact anteriorly, actually lowered joint force.11

Baad-Hansen, in 2007, demonstrated that there were reduced EMG forces during parafunction with anterior midpoint stop appliances, and in 2008, Stapelmann supported this same concept.12,13

The Anterior Midpoint Stop Advantage in OAT

Holding the mandible in a protrusive posture supported by an appliance does not add strain to the joint structure. The tendency to cause strain or sprain in a joint that leads to effusion and increased pain is most likely to occur during parafunction. Miralles’s studies demonstrated that there is a significant reduction of EMG activity in the elevator muscles during the parafunctional event with anterior midpoint stop appliances9 (see Figure 1).

Another real advantage of having only anterior contact is that inserting the appliance becomes less dependent on well-balanced posterior occlusion. The lack of posterior contact becomes even more significant as protrusive titration takes place and there is no concern about altered posterior contact.

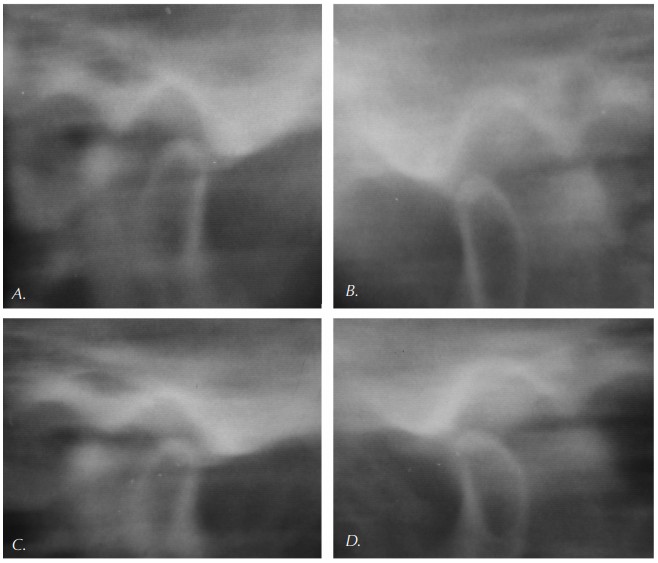

The Myth of Retrodiscal Compression Caused by Anterior Midpoint Stop Appliances

The prevailing misconception contends that parafunction in the absence of posterior contact will lead to posterior superior posturing of the condyle. The theory suggests this consequence will result in compressions of the highly vascularized and innervated retrodiscal tissues. Careful evaluation of the force vectors created by the combination of the masseter and anterior temporalis reveals that the mandible is not guided posteriorly by their action, but actually anteriorly and superiorly. The mandibular motion is very different in vivo than typically presented in two dimensional diagrams (see Figure 2).

Conclusion

Conclusion

Despite the preponderance of literature indicating otherwise, TMJ damage or joint pain remains a major contraindication for oral appliance therapy or a contributing factor in discontinuing efficacious oral appliance use. This misconception can preclude viable candidates from receiving OAT or lead well-intentioned but misinformed clinicians to discontinue use, therefore jeopardizing the quality of the patient’s general health.

It been noted that temporomandibular joint pain is not common with the use of oral appliance therapy for sleep disturbed breathing. Additionally, the likelihood of developing joint pain can potentially be decreased or eliminated when it occurs by moving the dental contact further anterior or utilizing anterior midpoint stop appliances.

After reading Drs. Glassman and Malizia’s discussion of anterior midpoint stop appliances, read their guide to critical thinking about empiricism, science bruxism, and sleep here: https://dentalsleeppractice.com/ce-articles/bruxism-sleep-disturbed-breathing-a-guide-to-critical-thinking-about-empiricism-science-bruxism-and-sleep/

- Anandam, A., et al., Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnoea treated with continuous positive airway pressure or oral appliance: An observational study. Respirology, 2013. 18(8): p. 1184-1190.

- Boyd, S., et al., Effective Apnea-Hypopnea Index (“ Effective AHI”): A New Measure of Effectiveness for Positive Airway Pressure Therapy. Sleep, 2016. 39(11): p. 1961-1972.

- Tsuda, H., et al., Craniofacial Changes After 2 Years of Nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Use in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Chest, 2010. 138(4): p. 870-874.

- Schmidt-Nowara, W., et al., Oral appliances for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep, 1995. 18(6): p. 501-10.

- Schmidt-Nowara, W., Recent Developments in Oral Appliance Therapy of Sleep Disordered Breathing. Sleep Breath, 1999. 3(3): p. 103-106.

- Doff, M., et al., Long-term oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a controlled study on dental side effects. Clin Oral Investig, 2012. online: p. 1-8.

- Blumenfeld, A., et al., Patterns of Use for an Enhanced Nociceptive Trigeminal Inhibitory Splint. Inside Dentistry, 2011. 7(11).

- Costen, J.B., A syndrome of ear and sinus symptoms dependent upon disturbed function of the temporomandibular joint. 1934. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, 1934. 106(10 Pt 1): p. 805-19.

- Nitzan, D., Intraarticular pressure in the functioning human temporomandibular joint and its alteration by uniform elevation of the occlusal plane. J Oral Maxillofac Surg., 1994. 52(7): p. 671-9.

- Miralles, R., et al., Influence of protrusive functions on electromyographic activity of elevator muscles. Cranio, 1987. 5(4): p. 324-32 contd.

- Hattori, Y., et al., Occlusal and TMJ loads in subjects with experimentally shortened dental arches. J Dent Res, 2003. 82(7): p. 532-6.

- Baad-Hansen, L., et al., Effect of a nociceptive trigeminal inhibitory splint on electromyographic activity in jaw closing muscles during sleep. J Oral Rehabil, 2007. 34(2): p. 105-11.

- Stapelmann, H. and J.C. Turp, The NTI-tss device for the therapy of bruxism, temporomandibular disorders, and headache: where do we stand? A qualitative systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health, 2008. 8(1): p. 22.

Barry Glassman, DMD, has earned Diplomate status with the American Board of Craniofacial Pain, the American Academy of Pain Management, and the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine. He is also a Fellow of the International College of Craniomandibular Disorders. He is on staff of the Lehigh Valley Hospital network and serves as clinical instructor in Craniofacial Pain and Sleep Disorders. Among his recent publications are The Effect of Regional Anesthetic Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block on Self-Reported Pain in Patients with Status Migrainosus in Headache, and The Curious History of Occlusion in Dentistry in Dentaltown. He teaches and lectures internationally on orofacial pain, joint dysfunction, and sleep disorders.

Barry Glassman, DMD, has earned Diplomate status with the American Board of Craniofacial Pain, the American Academy of Pain Management, and the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine. He is also a Fellow of the International College of Craniomandibular Disorders. He is on staff of the Lehigh Valley Hospital network and serves as clinical instructor in Craniofacial Pain and Sleep Disorders. Among his recent publications are The Effect of Regional Anesthetic Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block on Self-Reported Pain in Patients with Status Migrainosus in Headache, and The Curious History of Occlusion in Dentistry in Dentaltown. He teaches and lectures internationally on orofacial pain, joint dysfunction, and sleep disorders. Don Malizia, DDS, limits his practice to upper-quarter chronic pain and sleep disturbed breathing at the Allentown Pain & Sleep Center in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

Don Malizia, DDS, limits his practice to upper-quarter chronic pain and sleep disturbed breathing at the Allentown Pain & Sleep Center in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.