In part two of this four-part series, Sharon Moore explains the red flags of pediatric sleep-disordered breathing.

by Sharon Moore

by Sharon Moore

In part two of this four-part series, author, speech pathologist, and myofunctional practitioner Sharon Moore takes a deeper dive into the role of screening sleep, upper airway functions, and myofunctional disorders in the management of pediatric sleep disordered breathing.

Previously, we saw the ramifications of poor sleep on every aspect of a child’s development and functioning, making poor sleep a global health challenge.1,2,3 Furthermore, compromise can occur during critical periods of brain development in early childhood with a cascade of effects that can last a lifetime.4,5,6 The light at the end of this tunnel is that much of this is both avoidable and treatable, with dental teams playing a key role on the frontline for screening, education, and treatment of sleep disordered breathing.

Up to 40% of 4 to 10-year-old children are affected by sleep problems, and they are truly ‘in your face.’ Dr. Peter Eastwood et al demonstrated that facial bone structure is predictive of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).7,8,9,10 In fact, when a room full of ‘airway-focused’ health professionals gather, it is common to hear them predict potential sleep disordered breathing (SDB) from facial characteristics.

Unfortunately, 80% children with sleep problems are missed, dismissed, or misdiagnosed despite existing signs and symptoms.

The Challenges of Identifying and Treating Sleep Problems

SDB is the second most common sleep disorder, and recognized as a contributor to insomnia, the most prevalent, suggesting SDB is under-estimated.11,12

There are several issues contributing to low diagnosis levels:

- Not all sleep specialist centers recognize the full continuum of SDB: OSA, snoring, UARS, RERAs, and mouth breathing.

- Although the Apnea Hypopnea Index measures apneas, it doesn’t acknowledge other degrees of airway collapse that disrupt sleep.13

- Interpretation of existing sleep tests may not accurately identify SDB. For example, while PSG (polysomnography) measures body and brain signals extensively, SDB that does not lower oxygen levels, may be dismissed.

- A team care approach is critical; however, it is challenging to find compatible medical and allied health colleagues with the expertise and willingness to be part of a diagnostic sleep care team.

- Nighttime waking diagnosed as insomnia could be related to SDB.14

The challenges of SDB diagnosis raise the question: How can we screen for it?

Fortunately, dental teams are in the best seat in the house for the screening, education, and treatment of SDB.

Sleep Screening

The simplest way to screen a child’s sleep is using validated questionnaires that evaluate sleep health broadly and give insight to the existence of SDB. These are easy to incorporate into the clinical intake process.15,16,17 Some validated questionnaires include:

- BEARS (Bedtime Issues, Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, Night Awakenings, Regularity and Duration of Sleep, Snoring)

- PSQ-SRDB (Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire – Sleep-Related Breathing Disorder scale)

- SDSC (Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children)

- CAST (Children’s Airway Screener Taskforce – under development)

These questionnaires are predictive of SDB, in particular OSA. Symptom-based questionnaires can also be invaluable serving dually as education tools for patients.

The gold standard option for identifying SDB is polysomnography (PSG) and important for some but not all children. It is not easily accessible or affordable for many, nor necessary. Fortunately, there are other useful tools to identify significant symptoms and whether PSG is advisable, like; video, overnight pulse oximetry and even apps like Snore-Lab that track the frequency and intensity of nocturnal audible breathing.

Upper Airway Screening

With SDB, the whole of the upper airway is under scrutiny and any functional disorders of the upper airway (UA) and orofacial myofunctional (MYO) disorders, need to be identified. Multiple studies demonstrate the role of myofunctional intervention in successful management of pediatric SDB.18,19,20

UA and MYO screening go hand-in-hand. In SDB, narrowing or collapse of the UA can occur at multiple points, including collapse or narrowing of orofacial, nasal, pharyngeal or laryngeal morphology. Upper airway function is dynamically integrated with UA morphology and any restrictions or changes in morphology will change function and vice versa.

UA and MYO screening go hand-in-hand. In SDB, narrowing or collapse of the UA can occur at multiple points, including collapse or narrowing of orofacial, nasal, pharyngeal or laryngeal morphology. Upper airway function is dynamically integrated with UA morphology and any restrictions or changes in morphology will change function and vice versa.

Diagnosable disorders can occur in any part of UA from the front of the face to the larynx. Examples of this include dysphagia, dysphonia, nasal resonance disorder, epiglottis collapse related to laryngomalacia (this occurs in 3.9% of children presenting with SDB).21

Orofacial Myofunctional Screening

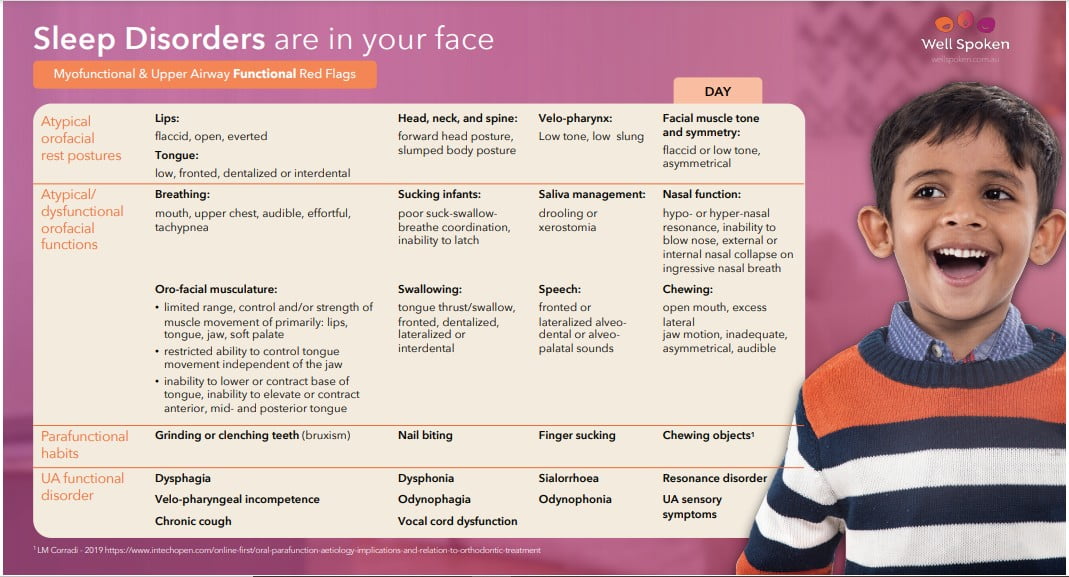

A MYO disorder refers to atypical function or rest postures in the mouth, face or throat and any co-existing parafunctional behaviors. To diagnose a MYO disorder, we look at:

- Function:

- Muscle rest postures

- Muscle movement patterns: breathing, chewing, swallowing (in infants, sucking), and speech

- Range, strength and control of movement of stomatognathic system

- Any related parafunctions

Then we consider factors that influence, or are associated with, those functions:

- Morphology:

- Skeletal: the size, shape and structure of the face and upper airway passages

- Tissue: health of the soft tissues in the face and upper airway, both extra and intra-oral, nasal, and pharyngeal

- Other relevant considerations:

- Medical, dental or orthodontic, early developmental history

An example of a MYO disorder that exists in conjunction with, or resulting from, discrepancies in skeletal shape or size is a high, narrow maxilla, preventing the tongue resting in its ideal position within the upper dental arch. The maxilla may be distorted by a thumb or finger sucking habit, altering tongue rest posture to a low-fronted position impeding tongue suction to the maxilla during sleep which assists maintenance of an open airway.

Identifying UA and MYO Red Flags

To screen for SDB, it’s important to evaluate UA and MYO red flags. These clinical markers for SDB are considered alongside relevant medical and early developmental history, such as pre- and post-natal history, feeding history, and diagnosed medical conditions or syndromes. This completes the picture of airway dysfunction or dysmorphology.

Other medical markers, particularly those relevant to ENTs, form a critical part of the picture. These are covered in more detail in Sleep-Wrecked Kids and Snored to Death for a full discussion on ENT markers relevant to pediatric SDB.22,23

Triaging Medical Severity, Urgency, and Priority

After screening and identifying SDB, examining the interplay of presenting symptoms and their consequences to quality of a child’s life and health, it’s time to determine the urgency and severity of the problem with the aim of organizing earliest possible treatment to mitigate neuro-cognitive and behavioral consequences of untreated SDB. Underlying medical issues impeding dental or myofunctional treatment efficacy need to be prioritized (e.g. untreated allergy with chronic nasal obstruction or reflux that perpetuates a cycle of sinus and nasal congestion, middle ear effusion and enlarged lymph tissue).24

Signs that expedited intervention is required include:

- Validated questionnaire scores indicating obstructive sleep apnea.

- Any consistent abnormal breathing during sleep.

- Poor quality sleep, including waking tired/unrefreshed, frequent unexplained awakenings, parasomnias, anxiety around sleep, extended head or body in odd positions, bed wetting after age 3-4, waking in a tangle of bedclothes.

- Poor energy management and self-regulation, including ADHD-like behaviors, excessive fatigue or poor Quality of Life measures.

In many cases, a team approach is required with other medical experts; ENT, sleep specialist, allergist, gastroenterologist, neurologist, or oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Untreated, medical issues can undermine any planned dental-orthodontic or myofunctional intervention.

The Role of Education in the Quest for Great Sleep

Given myths and misconceptions that persist around the role of sleep health and SDB, the role of education in a clinical context cannot be ignored. Screening tools that offer opportunities to educate are like gold, and perhaps the most important start-point is to dispel common misperceptions about sleep.

Once SDB and any co-existing UA or MYO disorder is identified, there is no time to lose. Normalizing oro-facial and UA functions need to start and continue until resolution and new healthy patterns are fully automated to support ongoing airway, dental, and occlusal health.

Fortunately, dental teams are on the frontline of this battle for great sleep. With our ability to screen for and treat problems early, we can ensure children get a great night’s sleep every night.

In “The Future Face of Sleep,” Sharon Moore discusses the ramifications of pediatric sleep-disordered breathing as well as the consequences of poor sleep on adult patients.

https://dentalsleeppractice.com/the-bigger-picture/the-future-face-of-sleep/

- Karen Bonuck, Ronald D. Chervin and Laura D. Howe, ‘Sleep-Disordered Breathing, Sleep Duration, and Childhood Overweight: A Longitudinal Cohort Study’, The Journal of Pediatrics 166, no. 3 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.11.001.

- Dale L. Smith, David Gozal, Scott J. Hunter, Mona F. Philby, Jaeson Kaylegian, Leila Kheirandish-GozalImpact of sleep disordered breathing on behaviour among elementary school-aged children: a cross-sectional analysis of a large community-based sample European Respiratory Journal 2016 48: 1631-1639; DOI: 10.1183/13993003.00808-2016

- Irina Trosman and Samuel J. Trosman Cognitive and Behavioral Consequences of Sleep Disordered Breathing in Children Sleep Medicine Center, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60611, USA Head and Neck Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA Med. Sci. 2017, 5(4), 30; https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci5040030

- Philby, M., Macey, P., Ma, R. et al. Reduced Regional Grey Matter Volumes in Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Sci Rep 7, 44566 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44566

- Kheirandish-Gozal L, Sahib AK, Macey PM, Philby MF, Gozal D, Kumar R. Regional brain tissue integrity in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Neurosci Lett. 2018;682:118-123. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2018.06.002

- Rosemary S C Horne, Bhaswati Roy, Lisa M Walter, Sarah N Biggs, Knarik Tamanyan, Aidan Weichard, Gillian M Nixon, Margot J Davey, Michael Ditchfield, Ronald M Harper, Rajesh Kumar, Regional brain tissue changes and associations with disease severity in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep, Volume 41, Issue 2, February 2018, zsx203, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx203

- Owens & Chervin, ‘Behavioral Sleep Problems in Children’, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/behavioral-sleep-problems-in-children

- Sarah Blunden, ‘Behavioural Sleep Disorders across the Developmental Age Span: An Overview of Causes, Consequences and Treatment Modalities’, Psychology, no. 3 (2012): 249–56, https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.33035.

- Sharon Moore, ‘Sleep Disorders are in your face’, in The 2nd AAMS Congress (Chicago, 2017).

- Eastwood P, Gilani SZ, McArdle N, et al. Predicting sleep apnea from three-dimensional face photography. J Clin Sleep Med. 2020;16(4):493–502.

- Barry Krakow, Natalia D. McIver, Victor A. Ulibarri, Jessica Krakow, Ronald M. Schrader Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial on the Efficacy of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Adaptive Servo-Ventilation in the Treatment of Chronic Complex Insomnia VOLUME 13, P57-73, AUGUST 01, Open Access Published: August 07, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.011

- Barry J. Krakow, Natalia D. McIver, Jessica J. Obando & Victor A. Ulibarri Changes in insomnia severity with advanced PAP therapy in patients with posttraumatic stress symptoms and comorbid sleep apnea: a retrospective, nonrandomized controlled study Military Medical Research volume 6, Article number: 15 (2019)

- Irina Trosman and Samuel J. Trosman Cognitive and Behavioral Consequences of Sleep Disordered Breathing in Children Sleep Medicine Center, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60611, USA Head and Neck Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA Med. Sci. 2017, 5(4), 30; https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci5040030

- Barry Krakow, Natalia D. McIver, Victor A. Ulibarri, Jessica Krakow, Ronald M. Schrader Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial on the Efficacy of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Adaptive Servo-Ventilation in the Treatment of Chronic Complex Insomnia VOLUME 13, P57-73, AUGUST 01, Open Access Published: August 07, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.011

- Shahid A., Wilkinson K., Marcu S., Shapiro C.M. (2011) BEARS Sleep Screening Tool. In: Shahid A., Wilkinson K., Marcu S., Shapiro C. (eds) STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales. Springer, New York, NY

- Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med. 2000;1(1):21-32. doi:10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00009-x

- Oliviero Bruni, Salvatore Ottaviano, Vincenzo Guidetti, Manuela Romoli, Margherita Innocenzi, Flavia Cortesi and Flavia Giannotti, ‘The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC): Construction and Validation of an Instrument to Evaluate Sleep Disturbances in Childhood and Adolescence’, Journal of Sleep Research 5, no. 4 (1996): 251–61, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.1996.00251.x.

- Camacho M, Certal V, Abdullatif J, et al. Myofunctional therapy to treat obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep.2015;38(5):669-675A.

- Guilleminault C, Huang YS, Monteyrol PJ, et al. Critical role of myofascial reeducation in pediatric sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med.2013;14(6):518-525.

- Leto V, Kayamori F, Montes MI, et al. Effects of oropharyngeal exercises on snoring: A randomized trial. Chest.2015;148(3):683-691.

- Thevasagayam M, Rodger K, Cave D, Witmans M, El-Hakim H. Prevalence of laryngomalacia in children presenting with sleep-disordered breathing. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1662-1666. doi:10.1002/lary.21025

- Sharon Moore, Sleep-Wrecked Kids: Helping Parents raise happy healthy kids one sleep at a time. (New York: Morgan James publishing 2019).

- David McIntosh, Snored to Death: Are You Dying in Your Sleep? (Maroochydore:, ENT Specialists Australia, 2017)

- Narang I, Mathew JL. Childhood obesity and obstructive sleep apnea. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:134202. doi:10.1155/2012/134202

- Andersen IG, Holm JC, Homøe P. Obstructive sleep apnea in children and adolescents with and without obesity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(3):871-878. doi:10.1007/s00405-019-05290-2

- David McIntosh, Snored to Death

Sharon Moore is an author, speech pathologist and myofunctional practitioner with 40 years of clinical experience across a range of communication and swallowing disorders. She has a special interest in early identification of craniofacial growth anomalies in children, concomitant orofacial dysfunctions and airway obstruction in sleep disorders.

Sharon Moore is an author, speech pathologist and myofunctional practitioner with 40 years of clinical experience across a range of communication and swallowing disorders. She has a special interest in early identification of craniofacial growth anomalies in children, concomitant orofacial dysfunctions and airway obstruction in sleep disorders.