by Bryce Williams, DDS, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon Assistant Professor, University of Utah Heath Care

Your Thursday clinic is completely booked. As you move from patient to patient you tackle each problem presented to you in the most efficient way that you can. Thomas, your patient in exam room 4, is doing well at his 6 month recall appointment and requires occlusal sealants today. Lisa in exam room 2, a 36 year-old female with primary snoring, has had a good response to the mandibular advancement device that you ordered and fitted for her and her primary physician is pleased with the treatment as well. In exam room 1 is Mitchell, a six year-old male is presenting for his very first visit to the dentist with his mother and his 12 year-old sister. Mitchell appears excessively hyperactive for his age and has difficulty paying attention to what you or his mother is saying to him. During your examination, Mitchell sits in his mother’s arms and begins to doze off towards the end of the exam, but wakes up after you stand up to wash your hands. Afterwards, Mitchell is interested to learn that he has 20 teeth and no cavities. The oral exam reveals that his tonsils are +1 in size, which is fairly small for his age. You prescribe a prophylactic cleaning today and a 6-month follow-up. Mitchell leaves the office, and his obstructive sleep apnea leaves with him.

Sleep apnea in the pediatric population typically has different manifestations compared with sleep apnea in the adolescent and adult population. This can make the diagnosis of sleep disordered breathing in the child much more challenging. Knowing the difference might mean uncovering undetected sleep apnea in one child and ruling it out in another. Diagnosis and effective treatment can mean improved academic and social performance for the child as well as allowing them to reach full developmental potential. In short, it can make a big difference in a child’s life and subsequent maturation.

In adults and adolescents, the primary symptoms most frequently consist of daytime somnolence, however, in the pediatric population this symptom may not be so easily observed by the child’s parents or other adults that they interact with daily. Children with sleep disordered breathing may tend to show signs of hyperactivity and inability to focus, which seems counterintuitive and therefore makes detection of this disease in children more difficult.1 For this reason, using a standardized screening questionnaire, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, is not as effective with children as it is with adults.2 In fact, a detailed history can be considered an inadequate tool for investigating sleep breathing aberrations in the pediatric population.2 There are several validated screening tools specific for the pediatric patient, that have a positive predictive power value as high as 85%.3,4

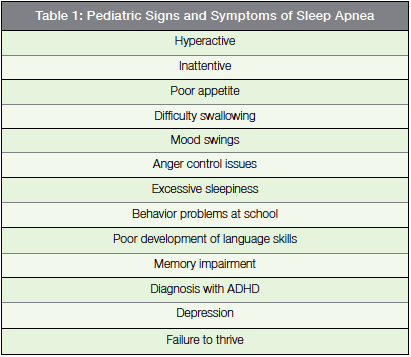

Knowing the risk factors, exposing the symptoms and vigorously pursuing subtle clinical signs may be the best method to approach pediatric sleep apnea. As young children have immature communication skills, they usually cannot accurately articulate their symptoms. An interview with a concerned parent can elucidate subtle cues such as hyperactivity, poor appetite, aggression and difficulty at school [see Table 1]. While several of these signs are associated with other diagnoses, namely ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), up to 30% of children with sleep apnea exhibit behavioral problems that closely mimic ADHD.5 Hearing such behaviors from the patient’s mother or father may prompt you into looking a little closer during the clinical examination to determine if this child may be at risk for obstruction of the airway at night.

The fictional story about Mitchell above also illustrates another important consideration: sometimes clinic signs do not assist in identifying a child at risk for obstructive sleep apnea. For instance, Mitchell had +1 tonsil size (equivalent to <25% obstruction of the posterior pharynx) found in his oral examination. If the same finding of a +1 tonsil was found in an adult, the observation might be considered insignificant. A tonsil size rating of +4 approximates 100% occlusion of the oropharynx by the tonsils [see Figure 1]. A recent systematic review revealed that the correlation between tonsil size and polysomnography-proven sleep apnea is poor.6 This is further elucidated in a meta-analysis putting the cure rate of adenotonsillectomy at 82% — which demonstrates that removal of the tonsils and adenoids is not necessarily the silver bullet in the child with obstructive sleep apnea that it was previously thought to be.7 In summary, occasionally the clinical exam of a pediatric obstructive sleep apnea patient can trick even the most seasoned clinician.

Because tonsillar hypertrophy may be absent in a small subset of children with obstructive sleep apnea, the head and neck assessment must look for additional anatomic evidence that could be causing nocturnal pharyngeal obstruction. For instance, the clinic exam must not only inspect the patient for enlarged tonsils and adenoids, but also report on growth disturbance, craniofacial abnormalities, relative neck size, absolute tongue size, lingual tonsil hypertrophy, turbinate hypertrophy, hypertensive blood pressure readings and evidence of gastroesophageal reflux. Additional referral to an internal medicine physician, pulmonologist and/or otolaryngologist to determine just how significant these findings are, but discovering them may be the first step in establishing a diagnosis of sleep disordered breathing in a child. An effective screening by a curious clinician can translate to additional diagnostic testing, to diagnosis, to treatment, to improvement or cure.

While adenotonsillectomy, or removal of the adenoid tissue and palatine tonsils, is still the most favored and effective treatment, it may not be as effective as previously thought with failure rates from 20-40%.8 Obesity, multilevel airway obstruction, and associated craniofacial syndromes, along with a host of other factors, can compromise the cure rate of adenotonsillectomy. In order to better understand the location of obstruction within the airway, whether it is singular or multi-level, drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) may be a helpful diagnostic adjunct to target surgical therapy specifically to the areas where obstruction is observed in real-time. DISE is performed by the treating surgeon in the operating room under the care of an anesthesiologist. A topical nasal decongestant and a topical anesthetic agent are used in the patient’s nasal cavity in preparation for introduction of a flexible endoscope. Finally, an infusion of a hypnotic/sedative agent (typically Propofol or Midazolam) is used to simulate sleep. The sedative agent is carefully titrated until the patient is in sleep-like state but spontaneous breathing is still maintained. At that point, a flexible endoscope is introduced into the patient’s nose and each level of the airway is observed in real-time to determine any if any anatomic abnormalities of the pharynx is present and to record the location(s) of occlusion of the airway. After the endoscopic examination, the patient can be placed under full general anesthesia and the surgeon can prescribe and immediately perform the needed airway surgery based on the findings during DISE. Alternatively, the surgeon can end the procedure and perform the procedure later on, after discussing the findings during the DISE with the patient’s legal guardians. DISE combined with surgical therapy in patients that have failed conservative measures (CPAP) has shown promising results.9

While adenotonsillectomy, or removal of the adenoid tissue and palatine tonsils, is still the most favored and effective treatment, it may not be as effective as previously thought with failure rates from 20-40%.8 Obesity, multilevel airway obstruction, and associated craniofacial syndromes, along with a host of other factors, can compromise the cure rate of adenotonsillectomy. In order to better understand the location of obstruction within the airway, whether it is singular or multi-level, drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) may be a helpful diagnostic adjunct to target surgical therapy specifically to the areas where obstruction is observed in real-time. DISE is performed by the treating surgeon in the operating room under the care of an anesthesiologist. A topical nasal decongestant and a topical anesthetic agent are used in the patient’s nasal cavity in preparation for introduction of a flexible endoscope. Finally, an infusion of a hypnotic/sedative agent (typically Propofol or Midazolam) is used to simulate sleep. The sedative agent is carefully titrated until the patient is in sleep-like state but spontaneous breathing is still maintained. At that point, a flexible endoscope is introduced into the patient’s nose and each level of the airway is observed in real-time to determine any if any anatomic abnormalities of the pharynx is present and to record the location(s) of occlusion of the airway. After the endoscopic examination, the patient can be placed under full general anesthesia and the surgeon can prescribe and immediately perform the needed airway surgery based on the findings during DISE. Alternatively, the surgeon can end the procedure and perform the procedure later on, after discussing the findings during the DISE with the patient’s legal guardians. DISE combined with surgical therapy in patients that have failed conservative measures (CPAP) has shown promising results.9

Despite Mitchell being a fictitious character, his situation represents an unknown number of undiagnosed pediatric sleep apnea patients that are suffering daily and are at risk of failing to thrive if they continue along that path. Because many of the symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing overlap with other conditions, misdiagnosis is a valid concern. As stated earlier, up to 30% of pediatric patients diagnosed with ADHD are actually suffering from a sleep-disordered breathing and may find improvement with CPAP or adenotonsillectomy.5 Refining our tools for detection and screening, enhancing our clinical examination skills, and obtaining the appropriate consultations with other medical and dental disciplines will, hopefully, limit the number of children that continue undiagnosed and untreated.

References

- Melendres MC. Lutz JM. Rubin ED. et al. Daytime sleepiness and hyperactivity in children with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics 114 (2004):768–75.

- Alexander NS. Schroeder JW. Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Pediatric Clinics of North America 60.4 (2013):827-840.

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, Chung SA, Vairavanathan S, Islam S. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea, Anesthesiology 108 (2008):812–821.

- Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ):validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepinessand behavioral problems, Sleep Med. 1 (2002): 21–32.

- Sedky K, Bennett DS, Carvalho KS. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and sleep disordered breathing in pediatric populations: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 18.4 (2014):349-56. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.12.003. Epub 2013 Dec 24.

- Nolan J, Brietzke SE. Systematic review of pediatric tonsil size and polysomnogram-measured obstructive sleep apnea severity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144 (2011):844–50.

- Brietzke SE, Gallagher D.The effectiveness of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134.6 (2006):979-84.

- Friedman M, Wilson M, Lin HC, et al. Updated systematic review of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy for treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140.6 (2009):800–8.

- Wootten CT, Chinnadurai S, Goudy SL. Beyond adenotonsillectomy: outcomes of sleep endoscopy-directed treatments in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 78.7 (2014):1158-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.04.041. Epub 2014 May 2.