With the increased awareness about sleep apnea among the public at large, more and more parents are raising questions about their kids’ snoring.

With the increased awareness about sleep apnea among the public at large, more and more parents are raising questions about their kids’ snoring.

DSP recently spoke with Dr. Rolf Maijer, an orthodontist who lectures on sleep problems and sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in kids and teenagers in North America and Europe.

DSP: “What prompted you to focus on the younger population regarding sleep apnea?”

RM: Over the years in my pedodontic and later in my orthodontic practice, parents have made comments like “You know, aafter you gave that appliance to Jonathan to widen his upper teeth, he stopped snoring” and “After Zoe started her expander treatment, she became a much better student in school.”

I finally connected the dots about nine years ago when a teacher that I was treating in my Nunavut practice [in the Canadian Arctic], made an observation about three of her students who were also in treatment. She observed that these three children had always been very sleepy in class, but after they started orthodontic (expansion) treatment, they were much more attentive. Suddenly, the comments from the past made a lot more sense. My “ah-ha” moment came when I realized what a profound impact that we as dentists can have in children’s overall lives – in their health, quality of life and ability to learn – if we start looking at our patient’s craniofacial structure and the oral cavity in the context of the airway and sleep.

Today, my wife and I spend a lot of our time actively reaching out to health care professionals, educators and parents to create awareness about the importance of sleep hygiene and the risks associated with sleep fragmentation and sleep disordered breathing in children.

DSP: What concerns you most about kids and their sleep health?

RM: Among my top concerns are how much time children (as well as adults) spend in front of screens, especially just before bed! It’s amazing how much time kids spend with personal electronics, such as phones and tablets in bed. The blue light emitted from laptops, tablets and cellphones is known to affect melatonin levels and can affect how easily children fall asleep, as well as their sleep quality. Kids are not the only ones at risk for poor sleep due to blue light exposure before bed. Adults are as well!

When it comes to sleep disordered breathing, our medical colleagues hardly pay attention to “primary snoring” in the child population, despite a growing body of literature over the last 15 years. Simple snoring together with periodic airway obstructions can have a very damaging effect on growth and development. A child’s executive function and the speed with which he or she comprehends subject matter in the classroom can also be affected.1

DSP: Why do you focus on speaking to pediatric and orthodontic clinicians?

DSP: Why do you focus on speaking to pediatric and orthodontic clinicians?

RM: Orthodontists and pedodontists are in a unique position to screen patients for SDB. They can readily see airway obstructions in their workups and radiographic material.

It is extremely important that these two specialties understand that their early diagnosis can have a tremendous impact the growth and development of young patients, as well as on their quality of life.

DSP: Why do we need to intercept SDB in children early? And what happens if we don’t?

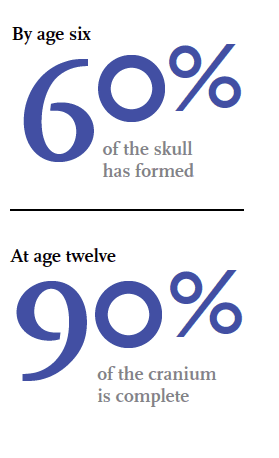

RM: The earlier that we identify and address SDB the better, because expansion of the upper arch and compensatory occlusal adjustments in the lower arch occur much more easily when the child is 6 or 7 than when we have a teenager. Remember that by age six, 60% percent of the skull has formed. At age twelve, 90% of the cranium is complete. Furthermore, an abnormal breathing pattern intercepted early allows us to stop the process that can lead to problems shown in Figure 1.

DSP: What are some of the things that a general dentist can do to screen their patient population for sleep issues?

DSP: What are some of the things that a general dentist can do to screen their patient population for sleep issues?

RM: General dentists also play an important role in screening kids for sleep problems and educating parents about the importance of sleep health. Keep in mind that about 12% to 16% of your pediatric population will have some form of SDB at some point between the ages of 6 and 18.2 A simple addition to your intake questionnaire about “regular” snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness and morning headaches will uncover a host of surprises. (It’s important to differentiate “regular” snoring from “occasional” snoring due to a cold or congestion.)

In our Dutch practice, we put up a sign in the waiting room that read: “Does anyone in your family snore? If so, please see front desk for information.” We saw 30 patients with SDB that day! If you learn that a parent snores or suffers from obstructive sleep apnea, use the opportunity to start a conversation with the patient or the parent about the child’s sleep.

It is important to train the whole office so that everybody is on the same page and speaks the same language. When we bring on a mentee, we don’t just work with the dentist. We train the entire office. It’s just as important for the front desk staff to recognize signs and symptoms of sleep issues among pediatric patients as it is for those that work chairside.

DSP: What should the dentist look for in a child patient?

RM: There are a number of tell-tale signs that should ring a bell.

- Venous pooling under the eyes

- Chronic mouth breathing while reading or playing an electronic game (e.g. in the waiting room)

- Forward tongue posture (tongue hanging out while reading or performing a task)

- Complaints of morning headaches

- Falling asleep in the waiting room or dental chair

- Acting out or boisterous behavior

DSP: How do you evaluate kids for sleep problems?

RM: The first step is to engage the parents. Ask questions about their child’s sleep hygiene. “What time does Henry go to bed? Is Jenny watching TV before going to sleep?”

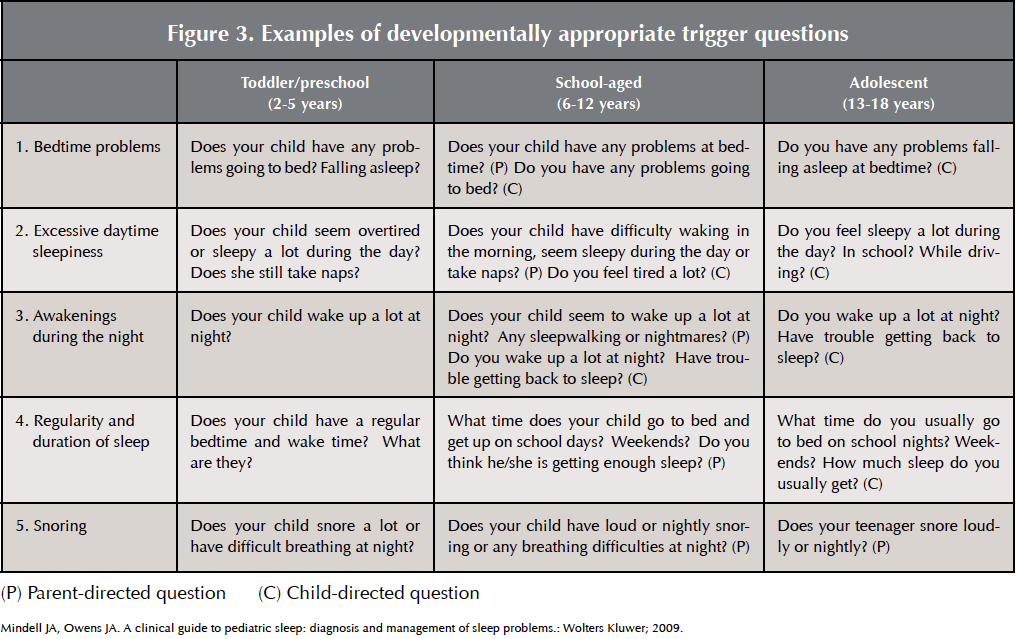

I use the BEARS Assessment which is a simple, 5-item pediatric sleep screening tool for use in primary care settings.3 This instrument helps you document information about five different domains of sleep health, including sleep hygiene and SDB. Since I like to have the results before I see the patient in the clinic, my assistant typically asks these questions of the parent or the child (depending on age.)

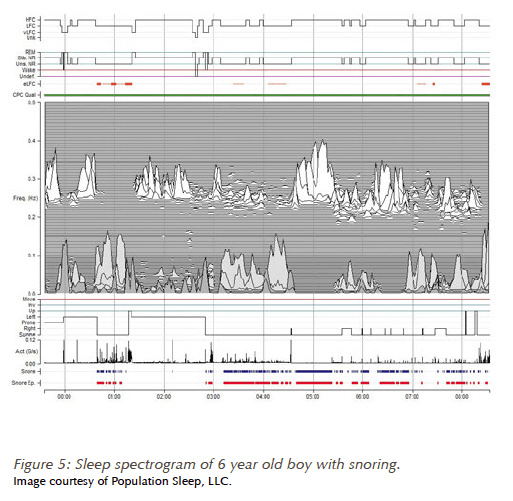

If the BEARS assessment indicates possible SDB issues, I typically issue an overnight SleepImage® test to gather additional objective data about the child’s sleep.[1]

This device is a simple, one-lead ECG monitor records the stability and quality of the child’s sleep. This screening tool can be used cost-effectively, especially in large practices. We use it in both our adult and pediatric practices and have started a new training program to help other dentists learn how to integrate it into their day-to-day practice.

The spectrogram produced by the SleepImage® helps me identify the presence of snoring, leg movements and effects of airway resistance (obstruction) on the child’s heart rate. It also shows to what degree the child’s sleep is fragmented and aids in explaining why their child experiences excessive daytime sleepiness. (See Fig 4)

As screening and communication tools, both the BEARS assessment and the SleepImage® spectrogram are invaluable. Depending on the findings, I will triage the case for further investigation or initiate treatment. Pediatricians and PCPs, alike, respond favorably when I attach a BEARS result and sleep-spectrogram to a letter requesting further assessment. When incorporated into routine practice, these tools facilitate EARLY recognition of sleep issues in patients!

DSP: We’ve heard that the “cure” for pediatric sleep disordered breathing is to send the patient to an ENT for removal of the tonsils and adenoids. What do you think?

DSP: We’ve heard that the “cure” for pediatric sleep disordered breathing is to send the patient to an ENT for removal of the tonsils and adenoids. What do you think?

RM: In the past, whenever tonsils and adenoids were removed, it was common that no further attention was given to airway obstruction issues post-surgery. We all assumed that the tonsils and adenoids (T&A) were the culprit and that removal was the cure. Several recent articles on post-surgical outcomes have shown, however, that many patients develop SDB sequellae two years post-surgery.4,5 The “obstruction problem” appears to be a lot more complex than simply eradicating an interfering tonsil or adenoid.

Due to the frequency that SDB reoccurs in children after T&A removal, it is absolutely imperative that we as clinicians recognize that a tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy may not solve the issue by just removing the obstruction. As noted by Bhattacharjee, we can’t rely on T&A as a “cure” for pediatric sleep disordered breathing.6

DSP: What are the “take home” points that you give to parents when you talk to them about their child and the child’s sleep?

We stress that habitual snoring will not “just go away.” Snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness are important warning signs of a potential problem that should not be ignored. We also connect the dots so parents understand the relationship between craniofacial anatomy and the sleep disordered breathing. If we find clinically that a child has a narrow arch (or crossbite) and a small mandibular arch, we explain that this “narrow bony box” may have a limiting effect on the airway.7 If the youngster is overweight, I bring out a picture that shows lateral pharyngeal fat pads restricting the airway.8

We want parents to realize that poor sleep and sleep fragmentation – no matter what the cause – is not healthy for their growing child. For this reason, we talk about the importance of good sleep hygiene and limiting the use of electronics before bed.

In cases where I do a screening and workup, I make sure that parents know that I will send a letter with my findings to the child’s pediatrician and other specialists involved in their care. Parents are generally very appreciative of the time you spend explaining why sleep is so important and giving them actionable information about how to improve their child’s sleep health.

DSP: Any final thoughts?

RM: Snoring and sleep apnea are in the news right now. You can’t pick up a newspaper or magazine without running into an article on sleep-related issues. As dentists, we can use this general awareness to shift the attention to our youngsters. We have to create awareness among parents, teachers and other health care providers that dentists play an essential role in catching sleep problems early. Dental intervention for sleep disordered breathing, when appropriate, can make a profound difference in a child’s health and quality of life.

References

-

Cortese S, Brown TE, Corkum P, et al. Assessment and management of sleep problems in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):784-796.

-

Katz E. Personal Communication. Toronto, Ontario 2013.

-

Mindell JA, Owens JA. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep : diagnosis and management of sleep problems. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

-

Dayyat E, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea: One or Two Distinct Disease Entities? Sleep medicine clinics. 2007;2(3):433-444.

-

Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, et al. Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):676-683.

-

Bhattacharjee R, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Spruyt K, et al. Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182(5):676-683.

-

Pirila-Parkkinen K, Pirttiniemi P, Nieminen P, Tolonen U, Pelttari U, Lopponen H. Dental arch morphology in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31(2):160-167.

-

Schwab RJ, Pasirstein M, Kaplan L, et al. Family aggregation of upper airway soft tissue structures in normal subjects and patients with sleep apnea. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2006;173(4):453-463.