Dr. Jagdeep Bijwadia compares types of OSA assessment. Which is better, AHI or oxygen saturation?

by Dr. Jagdeep Bijwadia

by Dr. Jagdeep Bijwadia

Obstructive sleep apnea is a significant and common medical disorder characterized by recurrent total or partial pharyngeal collapse causing temporary upper airway obstruction and drops in oxygen saturation during sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea is recognized as an independent risk factor for hypertension, arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation), coronary artery disease, and stroke. Metabolic disorders such as diabetes and disorders of lipid metabolism are also associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Hypoxemia, oxidative stress, systemic inflammatory responses, sympathetic activation, and sleep fragmentation have all been studied as markers for these subsequent cardio-metabolic disorders.

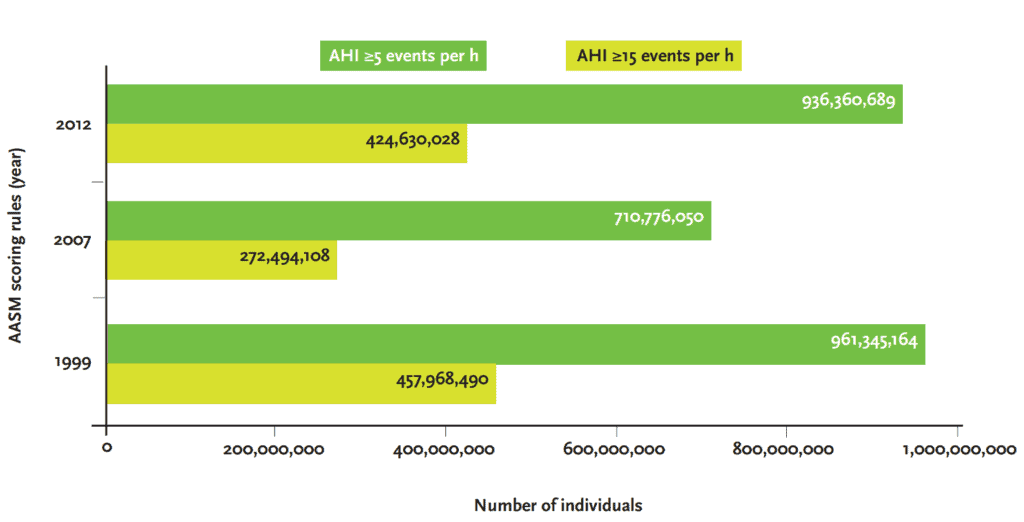

Obstructive sleep apnea impacts over a billion people worldwide. The overall incidence of obstructive sleep apnea in the US is estimated at 30% with men having a higher incidence than premenopausal women.1 Defining the disease using a reliable metric is critical. The ideal metric should be able to differentiate a disease state from normal, categorize the severity of the disease, predict outcomes, and allow us to measure and reduce the impact of the disease with treatment.

A recent special article published in the journal Sleep2 emphasized the need for alternative metrics to AHI for sleep apnea severity. This article will compare the apnea hypopnea index to various measures of oxygen saturation discussing the limitations and strength of each measure as well as exploring some of the newer metrics such as hypoxic burden that have been recently described.

AHI

Historically the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) has been the central metric for obstructive sleep apnea assessment. Although traditionally measured in polysomnographic studies, more recently home sleep testing has been demonstrated to be more cost effective and has been accepted as having equivalent accuracy in determining AHI for patients with a high suspicion of obstructive sleep apnea.

Using the AHI as the metric for obstructive sleep apnea however has several significant limitations. Inconsistency in the definition of sleep-disordered breathing events especially when measuring hypopneas is a significant concern. While first described by Block et al. as a respiratory event causing a 4% oxygen desaturation, subsequent task forces have variously defined hypopneas as a 50% reduction in airflow or a “clear amplitude” reduction or most recently a 30% airflow reduction. Associated drops in oxygen level during hypopneas has been defined as 3% or 4% or more recently 3% with an “option to report” a 4% desaturation. Hypopneas can also be considered present when there is limited airflow in the presence of an EEG based arousal. Note that some home sleep test devices use surrogates for EEG arousals such as changing snoring, pulse rate change or movement to identify hypopneas.2

Curiously the length of an apnea or hypopnea is not considered in the definition. One would imagine that a patient with prolonged apneas or hypopneas has significantly worse disease burden, but paradoxically, these patients with prolonged events may have a lower AHI as calculated by current standard definitions. Night-to-night variability in the AHI due to differing sleep stages, body position, or sleep fragmentation also represents a challenge.

One of the main strengths of the AHI is a large body of literature using AHI linking untreated obstructive sleep apnea and to a variety of comorbid conditions.

Some of the largest epidemiologic studies conducted in the past including the Sleep Heart Health Study,3 and the Wisconsin Cohort Study4 as well as many others have used the AHI as the metric linking increasing severity of obstructive sleep apnea to various adverse health outcomes including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, stroke, motor vehicle accidents, quality of life, and daytime sleepiness.

Oxygen Saturation Measures

When compared to the AHI, oxygen desaturation metrics may have some significant advantages. Two patterns of hypoxemia can be observed during sleep. Short intermittent and high frequency hypoxemia is seen in patients with obstructive sleep apnea due to recurrent airway collapse. Prolonged low frequency hypoxemia is seen in chronic obstructive lung disease and other pulmonary diseases as well as at high altitude. The major difference between these two is cycles of reoxygenation. The cyclic changes and hypoxemia and reoxygenation are similar to those observed with ischemia reperfusion injury and contribute to an increased production of reactive oxygen species which may be directly causative to adverse cardio-metabolic consequences.5

A commonly used oxygen desaturation metric is the ODI that represents the number of occurrences of desaturation 3% or 4% per hour of sleep. Note that it does not necessarily mean that the oxygen saturation falls below 90% since drops from 96-92% may be observed for example. Data from the European Sleep Apnea Database (ESADA) have shown that when both AHI and ODI are used in the same statistical model only ODI is independently associated with the prevalence of hypertension in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

The ODI, however, does not assess the length of oxygen desaturation consecutive to an obstructive apnea or hypopnea thus limiting its ability to assess obstructive sleep apnea effects accurately. To address this, two additional parameters have been recently suggested: the T90 and hypoxic burden.

T90 represents the amount of time the patient spent with saturations below 90% during their sleep.

A major limitation of the ODI is that it measures both hypoxemia due to obstructive sleep apnea as well as any underlying pulmonary causes. To overcome this limitation, a numeric was proposed by Azerbaijan et al.6 to measure hypoxic burden. Hypoxic burden was defined as a value reflecting the area under the curve on the oxygen saturation curve during desaturation episodes. This value considers the frequency, length, and depth of respiratory related oxygen desaturation.

This measure of hypoxic burden related to obstructive sleep apnea in the occurrence of cardiovascular complications was studied in two different large cohorts: The osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS)6 and the Sleep Heart Health Study. Researchers were able to demonstrate that the respiratory events related to hypoxic burden were independently associated with cardiovascular mortality. This association persisted after adjusting for a large number of potential confounders including prevalent cardiovascular disease as well as a AHI, T90, and sleep duration

In summary, hypoxia based metrics may be less prone to error, can be reliably measured by both polysomnography and home sleep tests, and be more reflective of disease burden and ability predict outcomes. It is likely that hypoxic burden and several other newer metrics will be used in conjunction to provide a much more accurate picture of OSA disease burden as research continues to uncover other markers.

Dr. Steven Poss’ CE, “The Tools that Make a Difference for the Practitioner and the Patient,” addresses OSA assessment. Subscribers can take the quiz and receive 2 CE credits! https://dentalsleeppractice.com/ce-articles/evaluating-and-treating-osa/

- Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, Nunez CM, Patel SR, Penzel T, Pépin JL, Peppard PE, Sinha S, Tufik S, Valentine K, Malhotra A. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Aug;7(8):687-698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. Epub 2019 Jul 9. PMID: 31300334; PMCID: PMC7007763.

- Malhotra A, Ayappa I, Ayas N, Collop N, Kirsch D, Mcardle N, Mehra R, Pack AI, Punjabi N, White DP, Gottlieb DJ. Metrics of sleep apnea severity: beyond the apnea-hypopnea index. 2021 Jul 9;44(7):zsab030. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab030. PMID: 33693939; PMCID: PMC8271129.

- Gottlieb, Daniel J. ; Yenokyan, Gayane ; Newman, Anne B. ; O’Connor, George T. ; Punjabi, Naresh M. ; Quan, Stuart F. ; Redline, Susan ; Resnick, Helaine E. ; Tong, Elisa K. ; Diener-West, Marie ; Shahar, Eyal Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident heart disease and heart failure: a prospective study. Circulation (New York, N.Y.), 2010, Vol.122 (4), p.352-360

- Hla KM, Young T, Hagen EW, Stein JH, Finn LA, Nieto FJ, Peppard PE. Coronary heart disease incidence in sleep disordered breathing: the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. 2015 May 1;38(5):677-84. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4654. PMID: 25515104; PMCID: PMC4402672.

- Blekic N, Bold I, Mettay T, Bruyneel M. Impact of Desaturation Patterns versus Apnea-Hypopnea Index in the Development of Cardiovascular Comorbidities in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022 Aug 25;14:1457-1468. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S374572. PMID: 36045914; PMCID: PMC9423119.

- Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Stone KL, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Terrill PI, Ancoli-Israel S, Ensrud K, Purcell S, White DP, Redline S, Wellman A. The hypoxic burden of sleep apnoea predicts cardiovascular disease-related mortality: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study and the Sleep Heart Health Study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 7;40(14):1149-1157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy624. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 7;40(14):1157. PMID: 30376054; PMCID: PMC6451769.

Dr. Jagdeep Bijwadia is board certified in internal medicine, pulmonary, and sleep medicine. He is founder and CEO of a national sleep telemedicine practice (Sleepmedrx) serving all 50 US states. He also serves as Chief Medical Officer for Whole You and is a clinical consultant for Ectosense. He currently holds a faculty position as Assistant Professor in the Department of Pulmonary Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at the University of Minnesota and has a private practice in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Dr. Bijwadia has been named top doc by the Minneapolis magazine as well as US News and World Report. He served as president for the Minnesota Sleep Society from 2016 to 2018 and is active in promoting sleep health in Minnesota. He also has an MBA from the University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis.

Dr. Jagdeep Bijwadia is board certified in internal medicine, pulmonary, and sleep medicine. He is founder and CEO of a national sleep telemedicine practice (Sleepmedrx) serving all 50 US states. He also serves as Chief Medical Officer for Whole You and is a clinical consultant for Ectosense. He currently holds a faculty position as Assistant Professor in the Department of Pulmonary Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at the University of Minnesota and has a private practice in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Dr. Bijwadia has been named top doc by the Minneapolis magazine as well as US News and World Report. He served as president for the Minnesota Sleep Society from 2016 to 2018 and is active in promoting sleep health in Minnesota. He also has an MBA from the University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis.