CE Expiration Date: November 10, 2025

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 750

Educational Aims

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to present the anatomic rationale for bilateral molar stabilization, an innovative alternative resulting in parallel arches that in fact establish a dilated posterior oral airway.

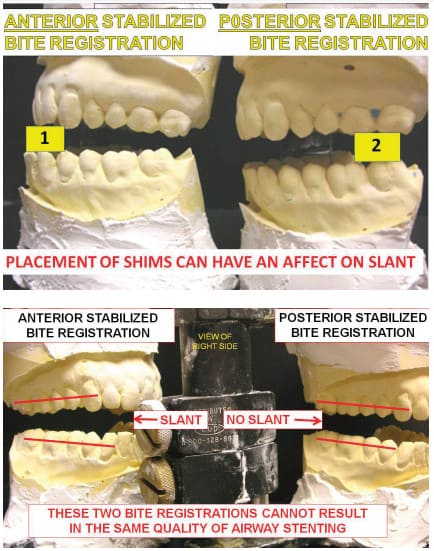

Two basic design principles for oral sleep apnea devices are: prevent collapse of the tongue on the pharynx and establish oral airway dilation (OAD). Commercially available devices for registering the interarch jaw relationship are based on anterior or incisal stabilization, almost universally resulting in slant, an acute angle between the maxillary and mandibular teeth narrower at the posterior than the anterior, and a negative for OAD.

Expected Outcomes

Dental Sleep Practice subscribers can answer the CE questions online to earn 2 hours of CE from reading the article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Think three-dimensionally about the condylar position during bite registration

- Reliably provide sufficient inter-arch space for device fabrication

- Gain confidence in setting expectations for patient accommodation to oral appliance therapy

In this CE, Dr Allen J. Moses discusses the design of oral appliance therapy and how specific dimensions determine effective treatment position.

by Allen J. Moses, DDS

Introductory Anatomy and Kinetics

Human beings are the only mammals to have a shared foodway and airway. As a result, adult humans cannot breathe and swallow at the same time. Therein the human species is unique in its tendency to succumb to Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), a disorder having morbid health consequences. OSA is a series of nocturnal periodic collapses of the tongue into the airway, causing obstructions.

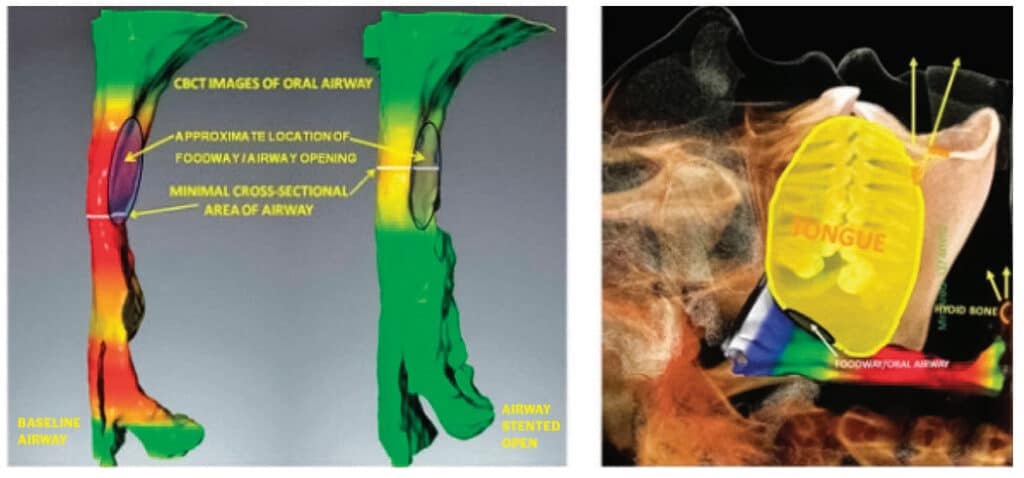

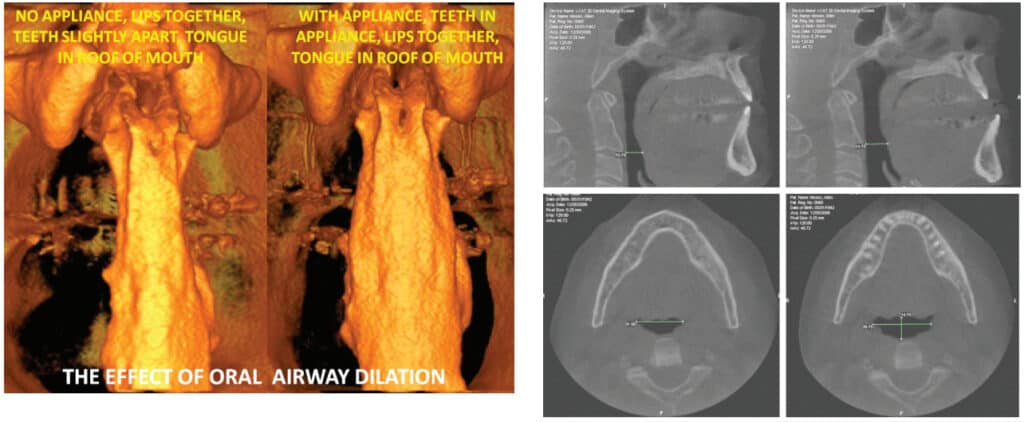

It is known that the diameter and volume of the pharynx can be dilated and stented by appliances that reposition parts of the oral apparatus. Dilation refers to getting the airway enlarged and stenting is keeping it open. Airway support during sleep is dependent on complex coordination of the interaction between the local bony architecture, neural, muscular, vascular, ligaments, cartilaginous disc and soft tissue.

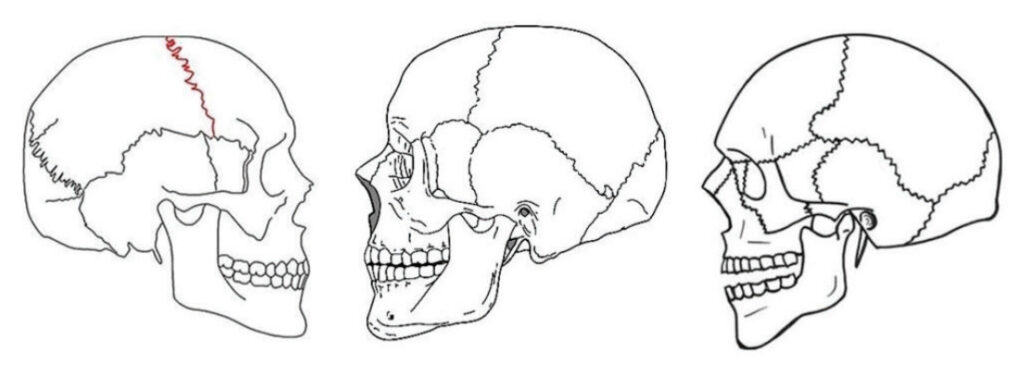

Normal interarch jaw position varies depending on the biological function being carried out, such as mastication, breathing, swallowing, incising, speaking, and screaming. Each distinct function utilizes different combinations of muscle activity and different muscle pressures. Each person has a unique combination of facial features and facial muscle alignment.

The interarch relationship for an intraoral sleep appliance is not a normally sustained biofunctional position for the mouth. The ideal interarch jaw position for an oral sleep appliance is optimal airway dilation and stenting with the lips comfortably closed. Four specific dimensions need to be considered to determine effective treatment position with an oral sleep appliance: protrusive, lateral, vertical and slant.

Slant

In an anterior stabilized interarch jaw registration, the acute angle seen between the plane of the mandibular teeth and the plane of the maxillary teeth is referred to as slant. It will always be narrower at the posterior than anterior. Understanding slant can affect the registration of the interarch jaw position for an intraoral sleep appliance.

Slant can affect airway size and patency. Slant can often be changed, depending on how the mandible is stabilized relative to the maxilla in registering the interarch jaw position for an intraoral sleep apnea appliance. Stabilization in the anterior incisor area will usually result in a different interarch jaw relationship, or slant, than from jaw stabilization in the molar area. Slant in a sleep appliance can compromise posterior airway diameter and volume, while simultaneously increasing anterior opening, making lip closure difficult during sleep.

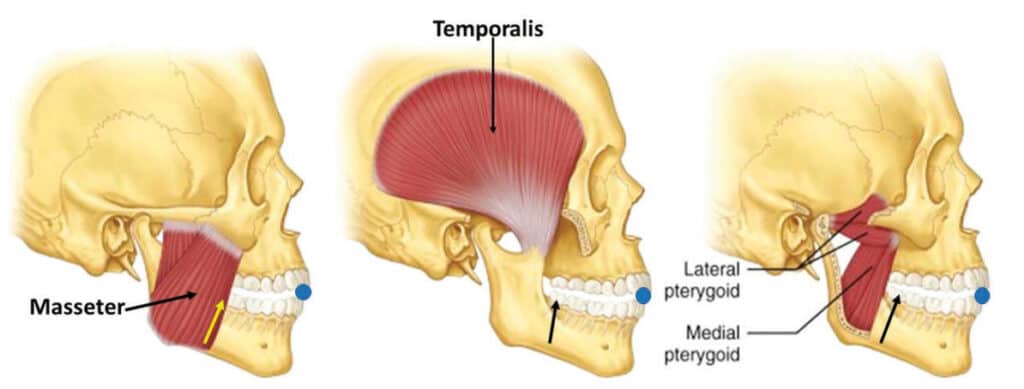

Anterior Stabilization

The interarch jaw position registered by an anterior stabilization device sets the mandibular condyles in an anterior and downward position outside the temporal fossae (See Figure 2). A hard anterior stabilization device resists jaw closure in the anterior segment of the mouth, but there is insufficient resistance to closure of the powerful elevator muscles in the posterior (see figure 6). In an anterior stabilized interarch position, the combined power of the masseters, pterygoids and temporalis pivots the condyles and discs back up toward the fossae and creates slant, reducing posterior airway space. Not only does anterior stabilization reduce posterior oral airway space, but the effect on the positions of the temporomandibular joints is not always desirable for patients having TMD problems.

Slant seen in an open mouth position without any stabilization, such as when screaming or biting into a club sandwich is not relevant to design of a sleep appliance for airway dilation. Such activity is within a normal range of movement and biological function of the oral apparatus. Holding the jaws in a fixed protrusive position all night beyond the vertical of rest position, in a TMJ position of questionable merit, with excessive muscle stress from the elevators and less than optimal airway dilation, is not within the normal function of the oral musculature. Slant in the interarch jaw registration for a sleep apnea patient appears to be a suboptimal treatment position.

The mandibular musculature is coordinated and balanced by a central pattern generator and curbed by proprioceptive reflexes and hard tissue limitations. The neural feedback mechanism is subject to anomalies that lead to an imbalance of the delicate normally harmonized muscles. Displacement of the mandible by an anterior stabilized bite registration device disrupts the harmonious function and introduces a disproportionate vertical increase in the anterior segment. With anterior stabilization and its accompanying slant, achieving the necessary posterior clearance may require introducing so much vertical in the anterior that the lips cannot stay comfortably closed at night and mouth breathing becomes an unwanted sequelae.

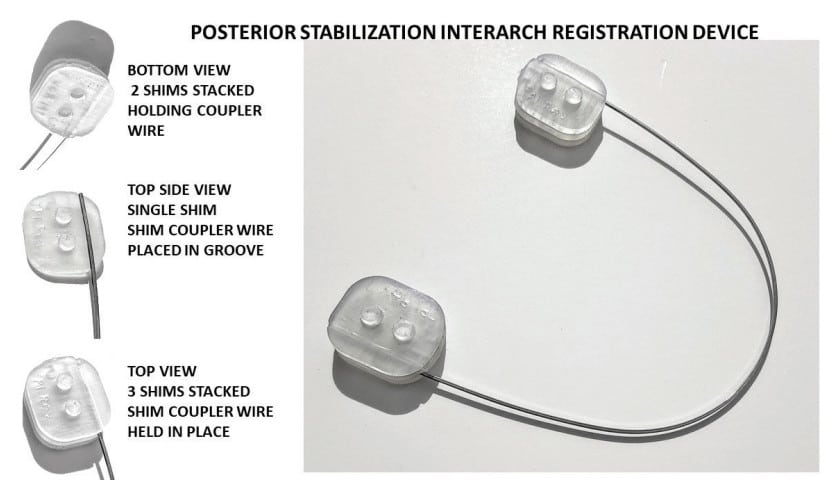

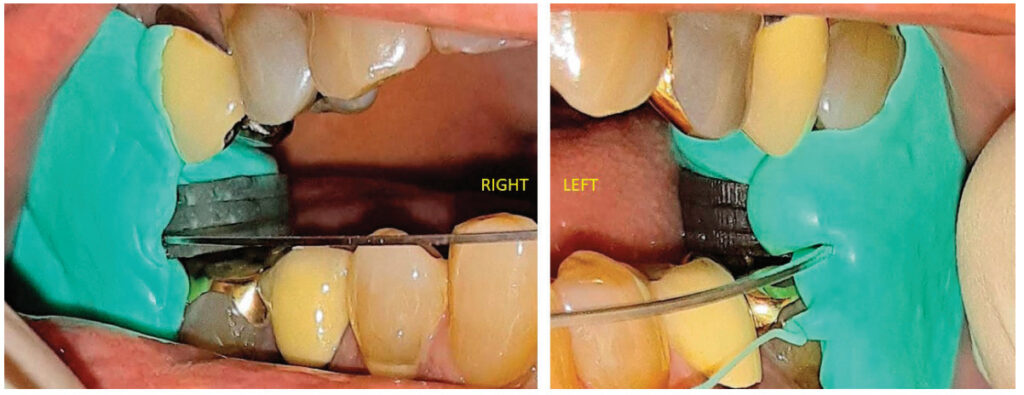

Posterior Stabilization

A posterior stabilization device positioned bilaterally in the molar areas to register the interarch bite position of a sleep apnea patient prevents or completely eliminates slant. The maxillary and mandibular planes are very close to parallel. Vertical height is gained in the posterior, where it is needed to optimally dilate the oral airway. Most of the vertical height is not gained as a consequence of excessive anterior height where its effect may be deleterious. A posterior stabilization device facilitates normal anatomic TMJ movement in registering the interarch jaw position for a sleep appliance.

Discussion

The objective of a dental sleep clinician is to establish a static position of the oropharyngeal airway components at optimal dilation and stenting. It is a static position because any jaw movement will change the airway dimension. This position is arrived at by manipulating the complex interrelationship between the temporomandibular joint, hyoid apparatus, elevator muscles and their antagonistic muscles, pharyngeal constrictor muscles, soft palate and tongue.

Oral sleep appliances are about a multidimensional increase in airway volume; not pure protrusive mandibular advancement. The objective of a dental sleep clinician is to establish a static position of the oropharyngeal airway components of optimal dilation and stenting.

It is a static position because any jaw movement will change the airway dimension. This position is arrived at by manipulating the complex interrelationship between the temporomandibular joint, hyoid apparatus, elevator muscles and their antagonistic muscles, pharyngeal constrictor muscles, soft palate and tongue.

It is not a normal functional position generated by the central pattern generator. There is no hard tissue bony support to the pharynx. The sole support for this nonfunctional position is in the interarch jaw registration and the fabricated oral sleep apnea appliance.

Registration of the optimal interarch jaw position presents a complex puzzle for sleep dentists. Finding the ideal position may be different for different face types and different case histories. Face types can change over the lifetime of a patient. Muscles have an abundance of contractile possibilities. Muscles do not always function in the same way in similar circumstances. The same muscle does not always function the same way in all people.

In sleep apnea patients correct airway size is of paramount importance. In TMD cases correct jaw position is of paramount importance. Many patients may have both TMD and sleep apnea. Posterior vertical dimension may be increased without disproportionately increasing anterior vertical dimension. There may not be one universal interarch jaw relationship that is correct for all patients.

Anterior stabilization interarch registration devices which appear to be the current mainstream method in dental sleep practices pose several difficult biological issues. Not only might anterior stabilization registration devices reduce posterior oral airway space, introducing an effect on the positions of the temporomandibular joints that is not desirable for patients having TMD problems, but they misdirect protrusive movement as much as 95% of the time. The directed movement of anterior stabilized bite registration devices is unidirectional and not consistent with natural jaw movement. It would seem reasonable to ask if there is another alternative.

Conclusion

There is certainly logic and anatomical principles that validate using a posterior stabilization device to establish the optimal stented position for an oral sleep appliance.

There is nothing that always works. Clinicians cannot always apply the same variables and factors to a universal patient model. Facts were presented here about differentiating anterior and posterior interarch jaw registration techniques. Clinicians now have a complex choice of whether to use anterior or posterior stabilization techniques to register the interarch jaw position for sleep appliances.

Clinical objective studies are warranted to determine the merit and physiological significance of the suggested shortcomings of anterior stabilization devices for registering the interarch treatment position for an oral sleep appliance as well as comparative studies to evaluate whether there is one better registration technique for interarch jaw position.

- The Human Bone Manual. White TD, Folkens PA, Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington MA, 2005

A complimentary sample of the ‘Molar Shim System for Posterior Interarch Registration’ used in this article is available for a limited time to dentists by request. Send name and mailing address to: www.themoses.com/info

The design of oral appliance therapy is the focus of “Effective Oral Appliances; By Definition and Design” by Dr. Mark T. Murphy. Read it here: https://dentalsleeppractice.com/effective-oral-appliances-by-definition-and-design/

Allen J. Moses, DDS, DABCP, D.ABDSM, was in private dental practice for 48 years in Chicago Illinois and assistant professor at Rush University Medical School in the Department of Sleep Disorders and Research for 13 years. He holds three US Patents for intraoral sleep devices and a Patent Pending for a shim system for registering the posterior interarch jaw relationship for intraoral sleep appliances. He was a member of the United States Food and Drug Administration Dental Products Panel for 10 years, has authored a book on temporomandibular disorders and over 30 scientific papers on TMDs and sleep dentistry. He was book review editor of Cranio for 10 years.

Allen J. Moses, DDS, DABCP, D.ABDSM, was in private dental practice for 48 years in Chicago Illinois and assistant professor at Rush University Medical School in the Department of Sleep Disorders and Research for 13 years. He holds three US Patents for intraoral sleep devices and a Patent Pending for a shim system for registering the posterior interarch jaw relationship for intraoral sleep appliances. He was a member of the United States Food and Drug Administration Dental Products Panel for 10 years, has authored a book on temporomandibular disorders and over 30 scientific papers on TMDs and sleep dentistry. He was book review editor of Cranio for 10 years.