CE Expiration Date: December 7, 2023

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 370

Educational Aims

Patients enter dental sleep practices with issues that can complicate treatment and which may not be evident upon physical exam or radiograph. Emotional trauma may adversely impact sleep quality, treatment compliance, and overall health. Understanding how to identify these issues and associated comorbidities, discuss them with patients, refer to mental health professionals when appropriate, and recognize what impact they’re having on treatment outcomes is crucial to providing comprehensive integrative care.

Expected Outcomes

Dental Sleep Practice subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading the article. Correctly answering the questions will exhibit the reader will:

- Define Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- Understand the relationship between ACEs, sleep disordered breathing (SDB), and potential health outcomes

- Recognize paths to broach mental health concerns with dental patients

- Identify how depression and ACEs may affect SDB treatment acceptance or adherence

- Possess the ability to incorporate an ACE screening protocol into the dental practice

Dr. Sunita Merriman’s CE delves into Adverse Childhood Experiences and how they impact the scope of the practice of dental sleep medicine. Read about the connections between insomnia and Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Table of Contents

Why Dental Sleep Practitioners Must Take a Seat at This Table

by Sunita Merriman, DDS

”What is spoken of as a clinical picture is not just a photograph of a sick man in bed; it is an impressionistic painting of the patient surrounded by his home, his work, his relations, his friends, his joys, sorrows, hopes and fears. Now all of this background of sickness which bears so strongly on the symptomatology is liable to be lost sight of in the hospital.”1

Although penned in 1927, if Dr. Francis W. Peabody sat at his desk today to review those words from his landmark article “The Care of The Patient,” it is very likely he would list “childhood history” to what he considered to be major components of an “impressionistic painting” of the clinical picture of a patient.

In addition to the impact and consequences of sleep deficiency and sleep disorders on adults, Pediatric Sleep Disordered Breathing has captured our attention, and continues, rightfully so, to be the subject of multidisciplinary research. A Google search of Pediatric Sleep Disordered Breathing on any given day yields over 670,000 results.

This bodes well for our society on many levels. But SDB can relate to childhood in a different way as we understand it.

Childhood Trauma or ACEs, Adverse Childhood Experiences

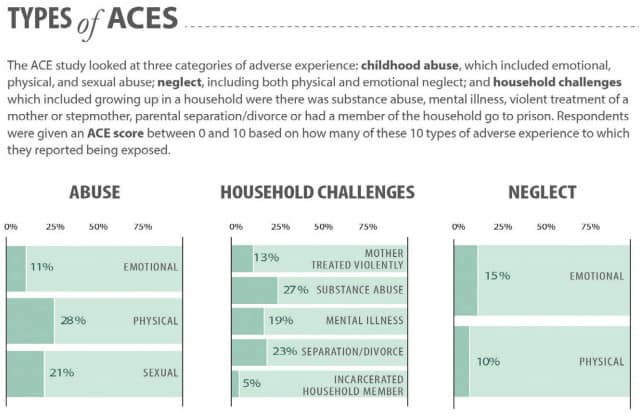

According to the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, ACE’s are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years) which could include experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect, witnessing violence in the home or community or having a family member attempt or die by suicide.2 The investigators of this landmark study also found a strong graded relationship between the breadth of exposure to abuse or household dysfunction during childhood and multiple risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults.

Prevalence of ACEs

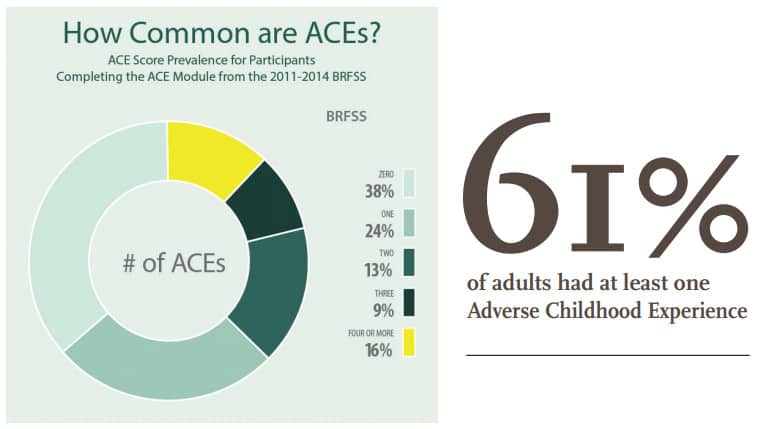

According to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, ACE’s are common, and their effects can accumulate over time. 61% of adults had at least one ACE and 16% had 4 or more. Females and several racial/ethnic minority groups were at greater risk for experiencing 4 or more ACEs.

What is Your ACE Score?

Most readers know what our weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, AHI, and and blood sugar levels are. We should also know our ACE score.

This questionnaire can be offered to our patients when we suspect that their medical, social, and psychological presentation suggests a history of childhood trauma.

It’s best to introduce the subject conversationally in a neutral tone, very much like you would ask their permission to do an oral examination at a dental appointment. It may be more sensitive of you to let them know that it’s okay for them to just disclose to you how many ACEs they feel apply to them, instead of which specific ones do.

ACEs and Their Long-term Impact on Health in Adulthood

Individuals with at least 4 ACEs were at increased risk of all negative health outcomes compared with those with no ACEs.3 Exposure to ACEs can evoke toxic stress responses, immediate or long term physiologic and psychologic impacts by altering gene expression, brain connectivity and function, immune system function, and organ function.4 There is a dose response relationship between ACEs and health outcomes. ACEs impact us through repeated stress activation, which causes our natural stress adaptive system to become maladaptive. The current understanding of the biology of stress on the brain informs us of our physiological response to the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis and the sympathetic-adrenomedullary system and resulting release of stress hormones. Children who suffer from ACEs experience toxic levels of stress, and dysregulation of their response to this stress, which leads to not only short-term changes in observable behavior but also less outwardly visible permanent changes in brain structure and function. These biological disruptions associated with ACEs are linked to greater risk for a variety of chronic diseases well into adulthood.5

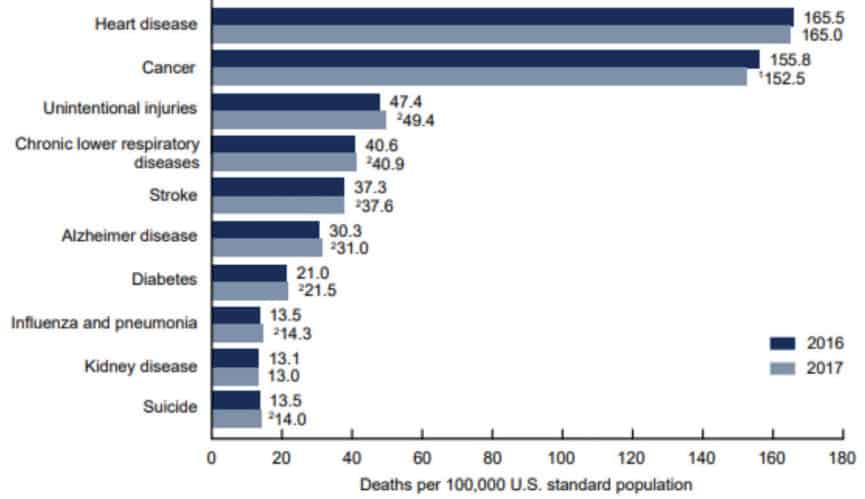

At least five of the 10 leading causes of death in the US (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, emphysema, cancer, and suicide) are associated with exposure to ACEs and have a graded relationship between ACE scores and health outcomes.6

Preventing ACEs could potentially translate to a reduction of up to 1.9 million cases of coronary heart disease, 2.5 million cases of obesity, and 21 million cases of depression.7

ACEs and Their Entry into Mainstream Conversation

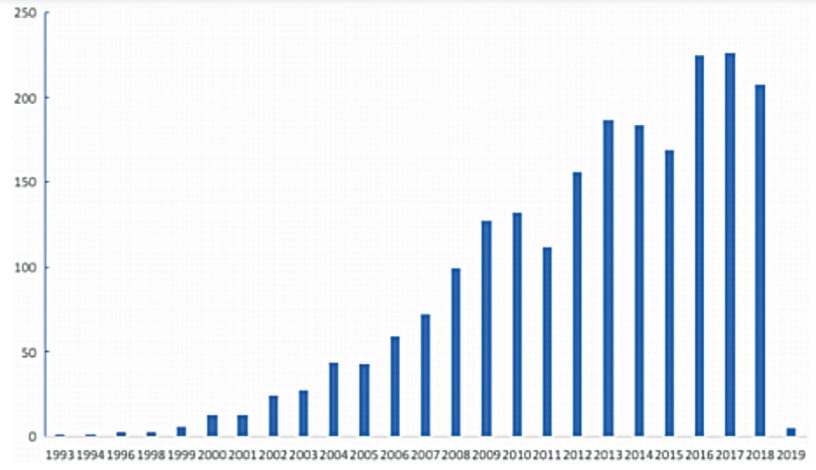

ACEs are not only occupying pages in medical journals but are now also appearing in mainstream media. Dr. Nadine Burke Harris’s TED talk “How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime” ignited interest among both the public and medical professionals regarding the hidden nightmare of ACEs and their impact on adult health and mortality. It has been viewed over 7.6 million times since it first aired in 2014.8 The sad fact is that widespread attention to ACEs came 16 years after the ACEs study by The Kaiser Institute and the CDC.

“Their pain is real – and for patients with mystery illnesses, help is coming from an unexpected source” reads the title of a now highly referenced article in The Globe and Mail written by Erin Anderssen in December 2018.9 It sheds light on a psychotherapy technique called Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISTDP) that has been shown to effectively treat, among many other conditions and disorders, the consequences of interruptions and trauma to human attachments and other childhood trauma.

Ms. Anderssen quotes professor, psychiatrist, and leading ISTDP researcher, Dr. Allan Abbass, “Shake things up, and what you find, in as many as 95% of cases, is a childhood story, one that’s been buried deep, carried like a malignant cell into adulthood, until it emerges as headaches or stomach pain or any number of physical ailments.”10

How do ACEs Affect the Realm of Dental Sleep Medicine?

In addition to the direct association of ACEs with sleep disorders, there are many other ways they impact the scope of practice of Dental Sleep Medicine as we will explore in this article.11

ACEs have been associated with self-reported sleep disturbances in adulthood. Additionally, the ACE score had a graded relationship to these sleep disturbances.12

A systematic review conducted by the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health, and Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, USA noted that there is a growing body of scientific knowledge that points to an association between ACEs and multiple sleep disorders in adulthood.13

Obstructive Sleep Apnea and It’s Treatment

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a highly prevalent disorder, characterized by recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction occurring during sleep. It’s associated with recurrent cycles of desaturation and re-oxygenation, sympathetic over-activity and intra-thoracic pressure changes leading to fragmentation of sleep.14 Consequently, symptoms of OSA may present as excessive daytime sleepiness, forgetfulness, impaired concentration and attention, personality changes, and morning headaches.15 Untreated, OSA has many potential consequences and adverse medical associations including an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents, cardiovascular morbidity, and all-cause mortality.16,17

Sleep disorders contribute to lost work productivity and absenteeism but also lead to poor health outcomes such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, depression, occupational injuries, and premature mortality.18-22

OSA and Comorbidities

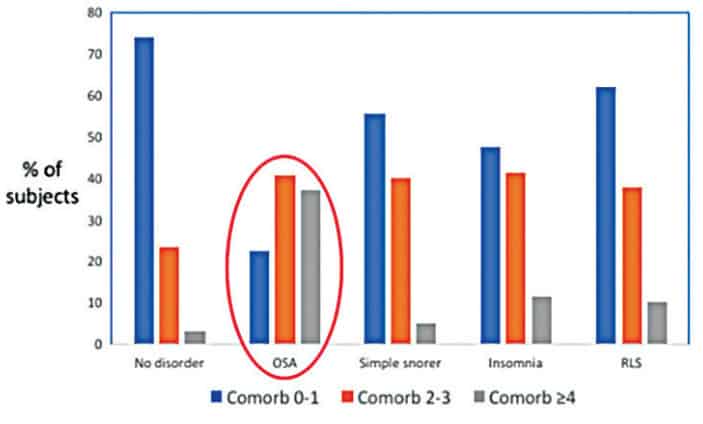

Comorbidity is associated with worse health outcomes, more complex clinical management, and increased health care costs.23 Even though there still remains a lack of consensus in the acceptance of an internationally recognized definition and conceptualization of comorbidity, there has been a consistent increase in interest in the role played by comorbidities in OSA as evident by the rising number of publications on this topic.24

OSA patients show a high level of prevalence of comorbidities compared to other sleep disorders. In addition, as a recent study from Taiwan confirmed, OSA patients showed a high prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and metabolic disorders.25 Many other co morbid disorders were also identified such as anxiety, insomnia, depression, gastroesophageal reflux, and chronic liver disease.

Given the high undiagnosed rate of OSA in the general population, its close relationship to common coexisting diseases may provide a way to recognize it.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Sleep Disturbances, and Depression

A recent study of the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey concluded that frequent snorting or stopping breathing during sleep was associated with higher prevalence of probable major depression regardless of factors like weight, age, sex or race.26

High rates of depression have always been found among patients with OSA. Sleep complaints and depression are bidirectionally related with as many as 90% of patients with depression having complaints regarding their sleep quality.27,28

About 75% of patients undergoing a major depressive episode will experience insomnia. Depression is also overrepresented in individuals with sleep disorders. Individuals with OSA may meet the criteria of being diagnosed with depression in occurrences as high as 24%-58%.29,30

COMISA (Co-Morbid Insomnia and Obstructive Sleep Apnea) is in Your Dental Sleep Practice

Individually, Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Insomnia are the two most common sleep disorders. Insomnia is defined as a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation (DIS), duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment.31

Together, they afflict an even larger population. Researcher Alexander Sweetman and his colleagues note that both OSA and insomnia include nocturnal sleep disturbances and impairments to daytime functioning.32

It was in 1973 when Christian Guilleminault and colleagues first documented the co-occurrence of insomnia and sleep apnea. “A new clinical syndrome, sleep apnea associated with insomnia, has been characterized. Repeated episodes of apnea occur during sleep. Onset of respiration is associated with general arousal and often complete awakening, with a resultant loss of sleep. An important clinical implication is that patients complaining only of insomnia may be suffering from this syndrome.”33

There is a renewed interest in COMISA as is evident by the number of publications on the topic in recent years. 30-50% of OSA patients report co-morbid insomnia symptoms, which reduces acceptance and use of CPAP therapy. This is an excellent opportunity for oral appliance therapy to be considered when appropriate for a patient.

Insomnia is a complex condition with a wide variety of etiologies. It is often self-treated by patients with OTC sleep aides which masks and helps avoid examination of the underlying issues. The effectiveness of CBTI (cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia) on the other hand is well-documented and is now the American College of Physicians’ first-line recommended treatment for insomnia.34

For those of us treating patients who suffer from COMISA or Insomnia, there are many challenges to getting our patients CBTI, directly impacting our ability to successfully relieve their symptoms.35

Important Considerations for Dental Sleep Medicine Practitioners

Any dentist who has provided oral appliance therapy to a patient diagnosed with OSA can relate to the frustration of achieving less than optimal results, often due to underlying comorbidities that are complicating treatment.36

Many of the comorbidities of OSA are conditions that also present in adults who have a score of 4 ACEs or more. Given this information, a diagnosis of OSA occurring along with one or more of its identified highly prevalent comorbidities may provide a way to recognize an opportunity to screen for a history of ACEs in an adult patient.

We must get comfortable asking our patients about their mental health and childhood as the starting point of our health history inquiries.

What if there are undiagnosed ACEs? These can add additional layers of complexity to the case, resulting in poor management and possibly even worsening of the patient’s condition.

How will a mandibular advancement device succeed against a backdrop of commonly occurring musculoskeletal pain reported by 11-29% of the population?37 50-80% of chronic pain patients complain of poor sleep. The sleep of middle-aged patients with chronic pain is comparable to that of insomnia patients.38 Many of this significant segment of our population who suffer from chronic pain do so as a result of the creation of neural pathways that are in response to trauma suffered in childhood or even as adults.39

Back pain, myofascial pain, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid pain are the most frequent conditions that lead to chronic pain. They are joined by chest pain, gastrointestinal issues, headaches, migraine, memory difficulties, muscle weakness, and other mind body problems as difficulties that are often co-morbid with anxiety, depression, personality issues, and/or trauma.

Many such physical and somatic symptoms are associated with underlying unconscious processes that sabotage any chances of success at alleviating symptoms of OSA. Unless these patients are treated for their mental, emotional, and psychological injuries and issues, their physical disorders persist and interfere in the resolution of their sleep disorders.

So, we must expand our collaborative relationship circle to include mental healthcare professionals, trauma informed practitioners and integrative care physicians. These relationships are vital and potential bidirectional patient referral sources as well as opportunities to exchange knowledge. CPAP tolerance amongst PTSD patients and those who have suffered different types of trauma have been suggested to be low, so oral appliance therapy for OSA would be a great addition to their care.40

Psychophysiological disorders are slowly gaining recognition in the general medical community as having underlying psychological sources of origin for the medical conditions in disabled workers who suffer from chronic pain and other conditions.

These individuals often have associated sleep disorders, and when they show up in our offices, present a severe challenge to successfully treating them if we do not take their total health into account; both physical and mental.

Conversely, when they seek care from integrative medicine practitioners, due to the high prevalence of OSA associated with these disorders, it would be prudent for them to refer their patients to be diagnosed and treated for OSA when appropriate. Having a Dental Sleep Practitioner on their team would be of great benefit to their patients.

A Case Study

A few years ago, a 67 year-old female presented to me complaining of “Fatigue, morning headaches, anxiety, depression, witnessed cessation of breathing by my bed partner, frequent snoring, gasping for breath and nighttime choking spells that wake me up from my sleep”

Her medical history was significant for acid reflux, autoimmune disorder, high blood pressure, chronic fatigue, chronic pain, depression, difficulty sleeping, fibromyalgia, hypertension, osteoporosis and sleep apnea. Her accompanying HST report showed her AHI to be 4.1 and her RDI to be 46.2.

The patient was referred to me by her sleep physician due to her intolerance to CPAP therapy.41

After a thorough history and clinical evaluation, I realized that her complaints of insomnia had not been addressed and recommended she see a psychologist for CBT-I first. I then fabricated a custom oral appliance for her.42 After insertion of the appliance and titration instructions, the patient had little success with the relief of her symptoms other than snoring. She requested multiple appointments with me for complaints of areas that ‘burned’ and ‘hurt’ due to appliance wear, bite issues, and difficulty tolerating the appliance for more than a few consecutive nights. For each complaint, there were no corresponding visible clinical presentations to treat or adjust.

These visits were starting to become frustrating for both of us. I could also see the increasing helplessness that her spouse felt as well. One day her husband mentioned that she just wasn’t getting better, even though they had seen 23 doctors in the previous 2 years.

Having developed a sincere relationship with my patient and her husband, I had learnt that there had been some recent tragic events in their family, in addition to her having a difficult childhood. Carefully reviewing the nature of her medical complaints, I decided to put emphasis on my conceptualization and understanding of my patient’s emotional state, instead of her diagnosis of OSA. I told them I thought that she may benefit from a consult with a mental health professional. They followed up on my referral to a psychiatrist with urgency.

I heard from my patient’s husband some months later. He told me that by the time they were able to see a psychiatrist/psychologist, she had deteriorated to the point where she had to be hospitalized for major depressive disorder. He could not thank me enough for spotting “the source of her problems that was missed by so many.”

This case did not end with me reducing a patient’s AHI below 5, but I felt it was a success. I suspect Dr. Peabody would have concurred.

Dental Sleep Medicine must look below the tip of the iceberg of our OSA patients, by not only focusing on their chief complaints, AHI, and oxygen saturation, but by being a part of the sweeping movement of the recognition and acknowledgement of their mind-body connection. Otherwise, we run the risk of being known as mere appliance makers.

After reading about the psychological connections between Adverse Childhood Experiences and sleep disorders, read more about the physical aspects of pediatric sleep disordered breathing in Sharon Moore’s article, “Sleep disorders are in your face,” here: https://dentalsleeppractice.com/the-bigger-picture/sleep-disorders-are-in-your-face/

References

- Peabody FW. The Care of the Patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882. doi:10.1001/jama.1927.02680380001001

- Vincent J. Felitti, MD, FACP, Robert F. Anda, MD, MS, Dale Nordenberg, MD, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245-258. PII S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017 Aug;2(8):e356-e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. Epub 2017 Jul 31. PMID: 29253477.

- Melissa T. Merrick, PhD; Derek C. Ford, PhD; Katie A. Ports, PhD; et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention — 25 States, 2015–2017 US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR / November 8, 2019 / Vol. 68 / No. 44

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012 Jan;129(1):e232-46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663. Epub 2011 Dec 26. PMID: 22201156.

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Arias E. National Center for Health Statistics data brief no. 328: mortality in the United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2018

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey data. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: 2017

- TED talk by Nadine Burke Harris, TEDMED- September 2014, https://www.ted.com/talks/nadine_burke_harris_how_childhood_trauma_affects_health_across_a_lifetime?language=en

- The Globe and Mail, December 8, 2018 “Their pain is real- and for patients with mystery illnesses, help is coming from an unexpected source”, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/article-their-pain-is-real-and-for-patients-with-mystery-illnesses-help-is/

- http://reachingthroughresistance.com/

- American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine, Scope of Practice, www.aadsm.org

- Chapman DP, Wheaton AG, Anda RF, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Liu Y, Sturgis SL, Perry GS. Adverse childhood experiences and sleep disturbances in adults. Sleep Med. 2011 Sep;12(8):773-9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.03.013. Epub 2011 Jun 24. PMID: 21704556.

- Kajeepeta S, Gelaye B, Jackson CL, Williams MA, Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: a systemic review. Sleep Med, Volume 16, Issue 3, March 2015, Pages 320-330

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. Epub 2013 Apr 14. PMID: 23589584; PMCID: PMC3639722.

- Cao M, Guilleminault C, Kushida C. Clinical features and evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea and upper airway resistance syndrome. In: Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. p. 1206–18.

- Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 May 1;165(9):1217-39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. PMID: 11991871.

- Marshall, NS., Wong, KK., Liu, P., Cullen, SR., Knuiman, M., & Grunstein, PR. (2008). Sleep Apnea as an Independent Risk Factor for All-Cause Mortality: The Busselton Health Study. SLEEP, 31(8), 1079-1085.

- Sarah K. Davies, Joo Ern Ang, Victoria L. Revell, et al. Sleep deprivation and the human metabolome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Jul 2014, 111 (29) 10761-10766; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1402663111

- Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, et al. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension: analyses of the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hypertension. 2006 May;47(5):833-9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217362.34748.e0. Epub 2006 Apr 3. PMID: 16585410.

- Combs K, Smith PJ, Sherwood A, Hoffman B, et al. Impact of sleep complaints and depression outcomes among participants in the standard medical intervention and long-term exercise study of exercise and pharmacotherapy for depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014 Feb;202(2):167-71. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000085. PMID: 24469530.

- Uehli K, Miedinger D, Bingisser R, et al . Sleep quality and the risk of work injury: a Swiss case-control study. J Sleep Res. 2014 Oct;23(5):545-53. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12146. Epub 2014 Jun 2. PMID: 24889190.

- Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585-592. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.5.585

- Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357-363. doi:10.1370/afm.983

- Bonsignore MR, Baiamonte P, Mazzuca E, Castrogiovanni A, Marrone O. Obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities: a dangerous liaison. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2019;14:8. Published 2019 Feb 14. doi:10.1186/s40248-019-0172-9

- Chi-Lu Chiang, Yung-Tai Chen, Kang-Ling Wang, et al. (2017) Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with sleep apnea, Annals of Medicine, 49:5, 377-383, DOI: 10.1080/07853890.2017.1282167

- Wheaton AG, Perry GS, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Sleep disordered breathing and depression among U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2008. Sleep. 2012;35(4):461-467. Published 2012 Apr 1. doi:10.5665/sleep.1724

- Franzen PL, Buysse DJ. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(4):473-481.

- Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1254–1269

- Millman RP, Fogel BS, McNamara ME, Carlisle CC. Depression as a manifestation of obstructive sleep apnea: reversal with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:348–351.

- Reynolds CF, 3rd, Kupfer DJ, McEachran AB, Taska LS, Sewitch DE, Coble PA. Depressive psychopathology in male sleep apneics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45:287–290

- International Classification of Sleep Disorders Third Edition, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014

- Sweetman A, Lack L, Bastien C. Co-Morbid Insomnia and Sleep Apnea (COMISA): Prevalence, Consequences, Methodological Considerations, and Recent Randomized Controlled Trials. Brain Sci. 2019;9(12):371. Published 2019 Dec 12. doi:10.3390/brainsci9120371

- Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Dement WC. Insomnia with sleep apnea: a new syndrome. Science. 1973 Aug 31;181(4102):856-8. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4102.856. PMID: 4353301.

- Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 19;165(2):125-33. doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. Epub 2016 May 3. PMID: 27136449.

- Kathol RG, Amedt JT, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Insomnia: Confronting the Challenges to Implementation Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:149-150. doi:10.7326/M16-0359

- Levine M, Bennett K, Cantwell M, Postol K, Schwartz D. Dental Sleep Medicine Standards for Screening, Treating and Managing Adults with Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine. 2018;5(3):XXX.

- Aytekin E, Demir SE, Komut EA, Okur SC, Burnaz O, Caglar NS, Demiryontar DY. Chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and the relationship between sleep disorder and pain level, quality of life, and disability. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015 Sep;27(9):2951-4. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.2951. Epub 2015 Sep 30. PMID: 26504332; PMCID: PMC4616133.

- Okura K, Lavigne GJ, Huynh N, Manzini C, Fillipini D, Montplaisir JY. Comparison of sleep variables between chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, insomnia, periodic leg movements syndrome and control subjects in a clinical sleep medicine practice. Sleep Med. 2008 May;9(4):352-61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.007. Epub 2007 Sep 4. PMID: 17804292.

- Psychophysiological Disorders- Trauma informed, Interprofessional Diagnosis and Treatment. Clarke, Schubiner, Clark Smith, Abbass, 2019

- Jaoude P, Vermont LN, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015 Feb;12(2):259-68. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201407-299FR. PMID: 25535907.

- Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: an update for 2015. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(7):773–827.

- Scherr SC, Dort LC, Almeida FR, et al. Definition of an effective oral appliance for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring: a report of the American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine 2014;1(1):39–50.

Sunita Merriman, DDS, graduated from New York University, College of Dentistry with honors in 1994. This was followed by a two-year General Practice Residency (1994-1996) at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park, New York and a mini-residency in Sleep Medicine and Dentistry in 2016 at the American Academy of Craniofacial Pain. She is the founder of the New Jersey Dental Sleep Medicine Center, NJDSMC in Westfield, New Jersey. Dr. Merriman is a Diplomate of both the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and the American Board of Craniofacial Dental Sleep Medicine. She is involved with presentations at the JFK Medical Center Sleep Fellowship Program for medical specialists who are training to be Sleep Specialists and is on staff at Overlook Medical Center in Summit, NJ. Dr. Merriman is also a poet and a writer. Her first book of poetry, “Stripping – My Fight to Find Me” is available at her website www.SunitaMerriman.com and Amazon. It is also available, as narrated by her, on Audible. She writes a blog at

Sunita Merriman, DDS, graduated from New York University, College of Dentistry with honors in 1994. This was followed by a two-year General Practice Residency (1994-1996) at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New Hyde Park, New York and a mini-residency in Sleep Medicine and Dentistry in 2016 at the American Academy of Craniofacial Pain. She is the founder of the New Jersey Dental Sleep Medicine Center, NJDSMC in Westfield, New Jersey. Dr. Merriman is a Diplomate of both the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine and the American Board of Craniofacial Dental Sleep Medicine. She is involved with presentations at the JFK Medical Center Sleep Fellowship Program for medical specialists who are training to be Sleep Specialists and is on staff at Overlook Medical Center in Summit, NJ. Dr. Merriman is also a poet and a writer. Her first book of poetry, “Stripping – My Fight to Find Me” is available at her website www.SunitaMerriman.com and Amazon. It is also available, as narrated by her, on Audible. She writes a blog at