Would making two simple changes to our strategy increase our chances of success?

Would making two simple changes to our strategy increase our chances of success?

by William M. Hang, DDS, MSD

Did you know very young children with reduced oxygen saturation during sleep can be afflicted with irreversible brain damage?1 If you’re surprised, you are not alone. Currently, lateral expansion and tonsil and adenoid removal are becoming more popular, but more can and should be done. After decades in the sleep arena, I have concluded that by making two changes to our treatment strategy, we can significantly increase our chances of success.

Focus on the A-P Plane of Space

First, we need to look at how the human skeleton has evolved. In two independent studies, research conducted by anthropologists Dr. Daniel Lieberman2 at Harvard and Dr. Robert Corruccini3 at Southern Illinois University, explain that the mid-faces of all people living in all industrialized countries are recessed relative to our ancestors. With both jaws more recessed, the soft palate and the tongue are also recessed which compromises the airway. As one pre-eminent sleep physician, Dr. John Remmers, explains, “…a structural narrowing of the pharynx plays a critical role in most, if not all, cases of OSA”.4

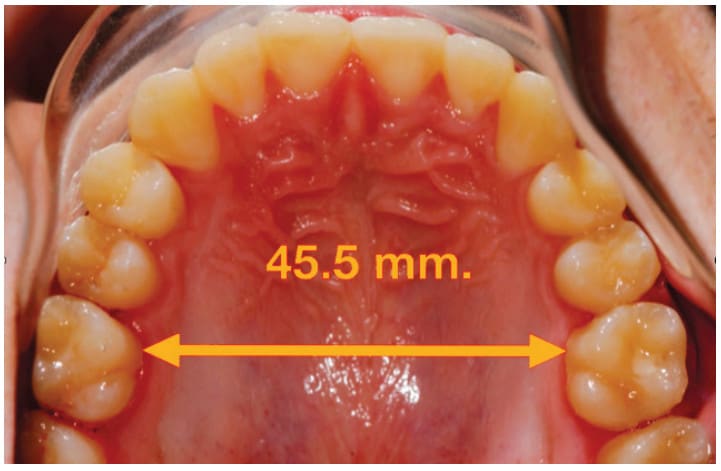

It is very easy to expand the maxilla laterally, but I believe we need to focus our energy on the A-P plane of space. Figure 1 shows a 16-year-old boy with an inter-molar width of 45.5 mm. He was treated by another practitioner with an expansion device to achieve this very broad width which is probably 10 mm wider than most children this age. Although successful in lateral expansion, the appliance used does little or nothing to develop the face forward. This patient’s profile is significantly recessed – and he snores! This case only reinforces my mantra, “You cannot expand your way out of an anteroposterior problem”.

Can we develop the jaws further forward? Would that forward development improve the airway? There is evidence in the literature that the answer to both those questions is “Yes”.5,6 Lateral expansion of the maxilla is part of the process used in the treatment described in these articles, but the A-P part of the treatment is the other strategy employed which goes beyond current trends.

Treat Children in the Primary Dentition

The second strategy is to treat children in the primary dentition. A recent Journal of Clinical Orthodontics survey of the profession indicated that orthodontists rarely treat before the first molars erupt at age 6.7 The adverse effects of reduced oxygen in a child’s brain won’t wait until age 6 to occur. Therefore, I can’t justify waiting to treat until we have permanent teeth in the mouth.

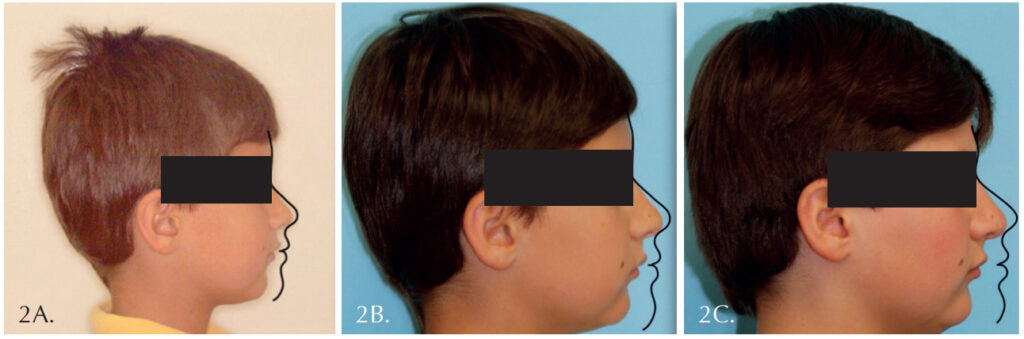

Figure 2 shows a child I first evaluated at 5 years 5 months of age with all primary teeth present. He was a slow dental developer and didn’t have all four upper incisors in place until he was almost 11 years of age. These pictures show that not only did his face not develop forward, it recessed more than a centimeter during that 5-year period. We began treatment when the upper four incisors were present. What I discovered was that too much unfavorable vertical vs. favorable horizontal growth had already occurred to get a more desired result. Even the best-cooperating patient and most experienced doctor could not overcome this growth deficit to get the desired amount of forward growth.

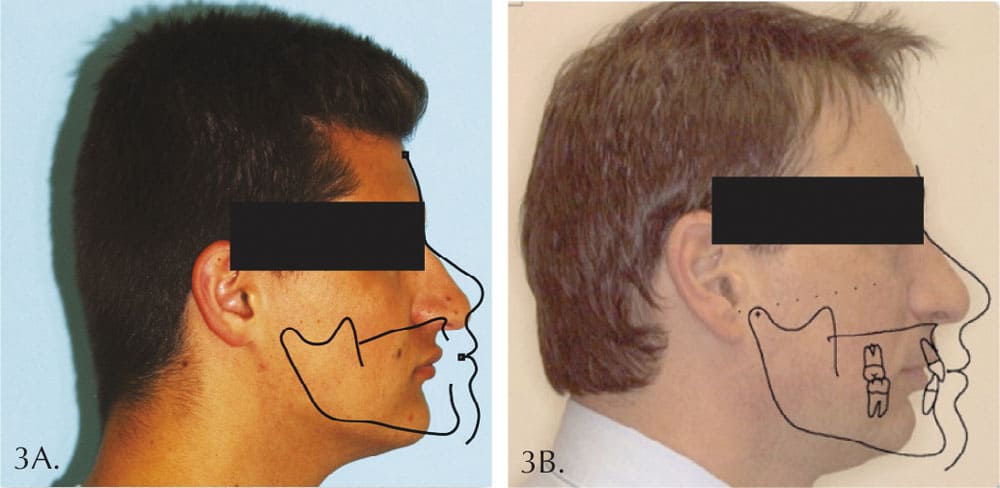

Figure 3 compares his profile at age 18 years 5 months of age with that of his father at age 35 years 9 months of age. Although our efforts did get some forward growth, our waiting caused us to start from a worse position with his lower face back more than a centimeter! His father suffers from OSA just like millions of others with faces similarly recessed. Prior to age 40, the father had problems associated with his OSA which resulted in having stents placed in his coronary arteries. The questions which concern me most are: With the boy’s profile recessed almost as much as his father’s, do you suppose he is at greater risk to develop similar problems? What if we had begun treatment for him prior to the eruption of any permanent teeth and had stopped the unfavorable vertical growth earlier?

This one patient was a game changer for me. I decided I had no choice but to treat when we first recognized the problem even if it was in the primary dentition. I could not, in good conscience, continue to do what I came to think of as “supervised neglect”. Waiting until four upper incisors were in the mouth, with predictable long-term impact so severe, I began to treat earlier.

Treating in the primary dentition is pretty scary for most orthodontists who are not prepared behaviorally to deal with kids this age. Pediatric dentists generally have the training to work with children under 6. Several pediatric dentists are recognizing this and understand that they are on the front lines of the airway pandemic that is affecting our population.

The following two patients were among some of the first I treated in the primary dentition. The two biggest factors in the success of these cases were beginning treatment early and the mother’s desire to have the best for her children.

Figure 4 shows the first patient at 4 year 10 months who had a gummy smile because her upper anterior teeth were already 13 mm back from an ideal position. We began treatment and advanced these teeth about 13 mm. Her permanent incisors eventually followed the primary teeth into good positions. The gumminess of the smile was eliminated, and her lower face was guided forward.

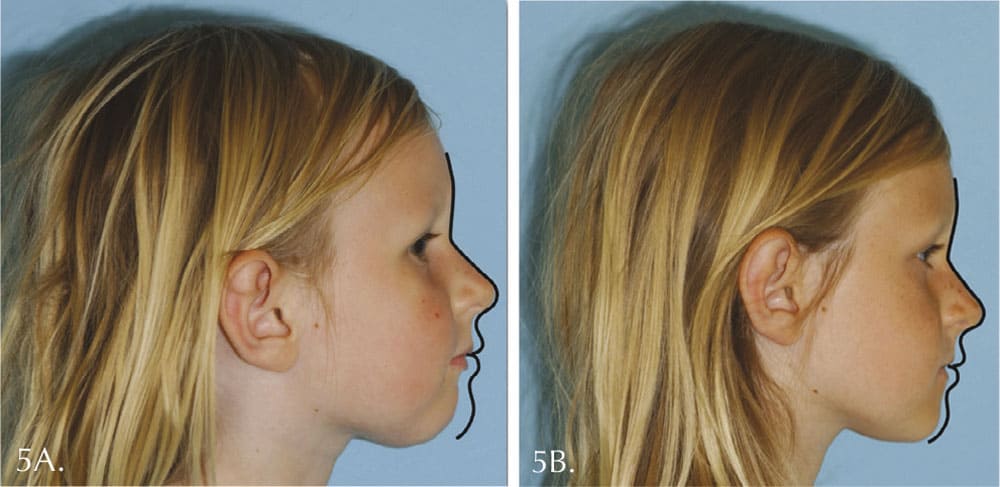

Figure 5 shows her sister with upper incisor teeth 12 mm too far back at 3 years 10 months of age. We advanced the upper anterior teeth about 12 mm and guided the mandible forward. Her profile improved even more than her sister’s.

Their mother is thrilled with both the esthetic and functional improvements we achieved. We are now performing the same treatment for the younger brother.

The ADA has made a big step forward thanks to Dr. Steve Carstensen’s work. In 2017 he helped the ADA issue a proclamation calling for dentists to screen for all forms of sleep disordered breathing in children.8 Unfortunately, not near enough progress is being made to implement a long-term strategy. From my experience, making two simple changes – focusing on the anteroposterior plane of space and treating in the primary dentition – increases our odds of success dramatically.

We are all on this journey together in uncharted territory. I do not have all the answers, but I hope to create an awareness of some of these problems, teach what I have learned over the years, and inspire others to develop even more effective treatments because “You can’t expand your way out of an anteroposterior problem.”

- Harper RM, Kumar R, Ogren JA, Macey PM. Sleep-disordered breathing: effects on brain structure and function. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013 Sep15;188 (3):383-91.

- Liberman DE. The Evolution of the Human Head 2011; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Corruccini, RS. How Anthropology Informs the Orthodontic Diagnosis of Malocclusion’s Causes. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press;1999.

- Remmers J. Personal communication. AACP 2002.

- Singh GD, Edina LE, Hang WM. Soft tissue facial changes using biobloc appliances: geometric morphometrics. Int J of Orthod. 2009;20:29-34.

- Singh GD, Garcia-Motta AV, Hang WM. Evaluation of the posterior airway space following biobloc therapy: geometric morphometrics. J of Craniomandibular Practice. 2007; 25:84-89.

- Keim RB, Vogels DS, Vogels PB. 2020 JCO study of orthodontic diagnosis and treatment procedures. JCO. 2020; LIV:731-745.

- ADA House of Delegates; The Role of Dentistry in the Treatment of Sleep Related Breathing Disorders. 2017

Bill Hang, DDS, MSD, has been in private practice since 1975 and is currently practicing in Agoura Hills, California. Having been traditionally trained, he extracted teeth for crowding and often retracted the teeth. For the last 40 years, however, he has been a pioneer in non-retractive treatments to improve the airway in patients of all ages and recently founded OrthO2Health.

Bill Hang, DDS, MSD, has been in private practice since 1975 and is currently practicing in Agoura Hills, California. Having been traditionally trained, he extracted teeth for crowding and often retracted the teeth. For the last 40 years, however, he has been a pioneer in non-retractive treatments to improve the airway in patients of all ages and recently founded OrthO2Health.